Holoholo, Mālolo (You go, flying fish!)

Story by Shannon Wianecki

Which Hawaiian animal can swim, “fly,” and “walk” on water? The humble mālolo, or flying fish. When a predatory ‘ahi (tuna) gives chase, the torpedo-shaped mālolo spreads its pectoral fins and prepares to escape. It rapidly sculls its tail (seventy times per second!) and rockets from the water, leaving beautiful zigzag trails on the ocean’s surface. Once airborne, mālolo can glide a quarter mile, traveling up to forty miles per hour. Some take flight at night; drawn to electric lights, they regularly crash-land on boat decks. Witnessing a school of fish in flight is magical—though sailors resent getting smacked by a midair mālolo.

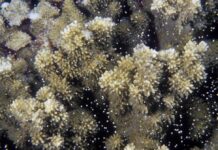

Nine flying-fish species, ranging from one to sixteen inches long, frequent Hawaiian waters during the summer months. They spawn in early spring, so more adult fish are present by May and June. Females lay eggs on anything that floats: seaweed, driftwood, palm fronds and, increasingly, plastic debris. This presents trouble for albatrosses, which feed on the eggs. A foraging albatross will swallow the entire lot—plastic and eggs—and later regurgitate it into the mouth of a chick.

Albatrosses aren’t the only ones ‘ono (hungry) for flying-fish roe; the eggs, known as tobiko in Japan, are standard fare at sushi restaurants. Harvesting the roe is easier than you might suspect. Fishermen float large mats of seaweed offshore and wait for flying fish to spawn on them. Once the mats are glistening with ripe eggs, they’re dragged to shore and their bounty extracted.

Traditionally, Hawaiians caught mālolo with massive bag nets. A lead fisherman would spot a school, and direct his fleet of canoes to drop its net in and encircle the fish. The wriggling catch was then covered with kauna‘oa (dodder) to prevent escape. Mālolo were considered delicacies, cooked in tī leaves or eaten raw with līpoa seaweed. You wouldn’t want to be called a “mālolo,” though. The word also refers to a fickle person who leaps from mate to mate.