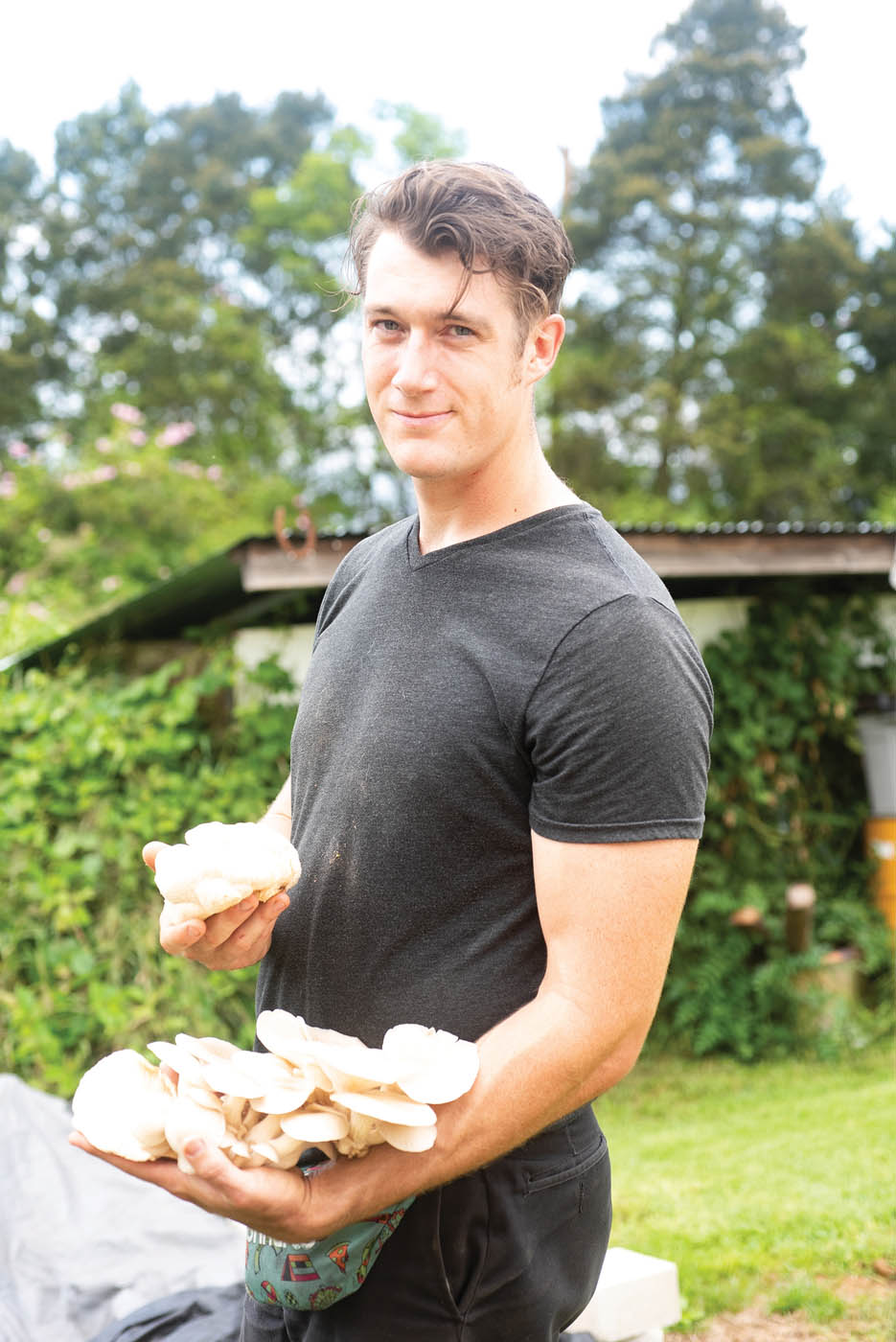

Story by Becky Speere | Photography by Mieko Horikoshi

The email came from the Hāna chapter of Hawai‘i Farmers Union United: “Mushroom Log Inoculation Workshop.” I quickly signed up. Weeks later, I was one of thirty HFUU members squeezed into the work shed at Hana Tropicals Oasis with Charles Tresidder, owner of Nō Ka ‘Oi Mushrooms, ready to drill holes into banyan logs and inject them with sawdust that had been inoculated with fungal culture. We worked like bumblebees, drilling and filling for two hours. “In a few months,” Charles told us, “when the bark starts to separate from the wood, drop it onto the ground to imitate a falling branch.” Huh? “What initiates fruiting is a physical disturbance, or a heavy soaking,” he explained. A spore colony growing on a rotting branch “knows” that when the branch becomes brittle and falls, there’s a short window before insects invade; the colony must reproduce before being consumed.

Today I’m in Charles’s Upcountry lab, watching him gesture toward petri dishes housed in incubators. The shallow, clear-glass vessels contain a moldy growth that—to put it nicely—looks like food gone bad. Charles says, “When I was eleven, I was a bit of a troublemaker, so my stepdad, a chemist, decided to reel me in. He took me into his lab and taught me about mushroom spores and tissue cultures.”

Charles eventually took a job in a Wisconsin kombucha plant, growing SCOBY, a “symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast” also called tea mushroom, tea fungus, or Manchurian mushroom—though it isn’t actually a fungus. In 2017 he moved to Maui and set up a mycology lab.

His fascination is understandable. Dormant mushroom spores can survive hostile conditions indefinitely. Activated, they multiply by the millions—in the right setting. Charles’s lab is a positive-pressure environment: air pressure is greater inside than out, so no unwanted microbe can enter. “You have to provide food for the [spores] with no bacterial contaminants,” he explains, also stressing the need for a stable electrical source to maintain constant humidity and temperature.

Reanimated, “a spore is still only one part of what is necessary to make a living fungi,” says Charles. “[It] contributes only a fraction of the genetic code, in the same way we humans need a copy of genes from both parents. Once two or more spores unite, a fungus begins to form; this is the official beginning of its life. If I inoculate a fertile substrate with the spores, cultures will form, and I’ll be able to get live clones. Depending on the variety, they won’t die for weeks or months after [being] brought out of refrigeration. But they do have an expiration date.”

We walk into the “cooking room,” where industrial-sized stainless-steel pressure cookers line up like miniature spacecraft awaiting takeoff. “I have to sterilize the [untreated] sawdust before inoculation,” Charles explains. “I finally found a local source for sawdust; my goal is to make 200 logs a month.” My eyes widen. “That’s a lot of mushrooms!” He tells me about his latest business venture with Lapa‘au Farm in Olinda: a new 4,000-square-foot mushroom-fruiting room he’s building with friend and business partner Michael Marchand.

Next to his lab, an enclosed area provides the filtered light and cool-evening and warm-day temperatures needed to grow fungi in bags sealed to retain the substrate’s moisture. They’re labeled: lion’s mane, oyster, reishi, shiitake. . . . Charles hands me a bag and says, “Try this shiitake. I think you may do well growing it in Huelo. Also try this reishi. China grows the bulk of our reishi imports in a similar environment to where you live.” I am stoked beyond words—mushroom’s got my tongue!

I head home to try growing mushrooms. Three months later, my science project is a success!

I grow three pounds of shiitake and a pound and a half of reishi. The shiitake tastes fresh and lacks the strong flavor that dry mushrooms exhibit. I dehydrate the reishi for teas and kombucha mixes.

Find Maui-grown Lapa‘au Farm mushrooms at the Wednesday Farmers Market at Waipuna Chapel, 17 ‘Ōma‘opio Rd., Kula; Saturdays at the Upcountry Farmers Market next to Longs Drugs, 55 Kiopa‘a St., Pukalani; and Lipoa Street Farmer’s Market, 95 E. Līpoa St., Kīhei.