PART 3 OF A 5-PART SERIES ON HAWAIIAN TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

Celestial navigation text by Judy Edwards (originally published as Wayfinders) | “Planting by the Moon,” text written by by Teya Penniman | Photography by Douglas Peebles

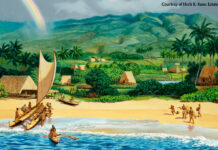

Thousands of years before Europeans began their first tentative ventures beyond coastal waters, Polynesians were exploring the vast Pacific. Aboard double-hulled voyaging canoes—some of the finest open-ocean sailing vessels ever engineered—those ancient travelers arrived in Hawai‘i, becoming farmers and fishers, warriors and kings—a people descended from what current-day navigator and Hawaiian son Nainoa Thompson called “the astronauts of our ancestors, the greatest explorers on the face of the earth.”

Once here, they used their meticulous observations of the heavens, their understanding of the movements of planets and stars, to thrive in this isolated archipelago.

Navigating by the Stars

The early Polynesian explorers had no tools for wayfinding—no sextant or magnetic compass, no GPS. Instead, they watched celestial bodies in the night sky, listened to the winds, felt the swells slap against, and move under, the wooden hulls. The flight of seabirds, behavior of clouds, patterns in the ocean and in the air informed their sense of where land might be. They lived in tune with everything around them, embedded in the pulse of the sea and the sky.

The constellation known in the West as the Southern Cross has a Hawaiian name: Hānaiakamalama, “foster child of the moon.” It’s visible in the Northern Hemisphere only up to the twentieth parallel—the latitude of the Hawaiian Islands. Watching for the distance between its top and bottom stars to equal the distance between the bottom star and the horizon helped Hawaiian navigators of old to find their way home.

The colonization of the Pacific in the 1700s by Europeans in their single-hulled ships was so swift and total that the art and science of traditional Polynesian migration were obliterated in the Polynesian Triangle—that vast area bounded by Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, Hawai‘i in the north, and Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the south—in just a few generations. The decline was so dramatic that theorists began to deny that deliberate Pacific navigation by the ancients had ever been possible.

In the 1970s, in response to theories that the Pacific Islands had been settled by accident or a stroke of luck, the newly formed Polynesian Voyaging Society of Hawai‘i built a sixty-foot voyaging canoe, a hybrid of natural and modern materials. They named the vessel Hōkūle‘a (“Star of Gladness,” a reference to Arcturus, the brightest star in the Northern Hemisphere and the guiding star for Hawaiian navigators), and in 1976, with the help of one of the last traditional Polynesian navigators in the world, a man from Satawal named Mau Piailug, they sailed Hōkūle‘a to Tahiti and back in triumph.

Four years later, mentored by Mau, the Society did it again. Chad Kalepa Baybayan, now navigator in residence at the ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, was aboard.

“When I sailed in 1980 it was like stepping back in a time machine,” he recalls. “The black silhouette of a crab-claw sail against the starry backdrop . . . at that moment you are as close to your ancestors as possible.”

Between 1985 and 1987, the Society sailed Hōkūle‘a surely and steadily around the islands of the Pacific and back to Hawai‘i, putting to rest forever the idea that the movement of Polynesians around the Pacific was anything less than adroit and deliberate.

Nainoa Thompson was the first contemporary Hawaiian to master the Polynesian art of navigation. He schooled himself in Western academics before learning from Mau the more subtle but powerful older ways of navigating. Baybayan says this hybrid approach is now the way young navigators train. It’s still an indigenous art, but there’s a lot of science involved.

“In the seventies, there was so much we had to learn,” Baybayan recalls. “We were just trying to stay afloat. As we got more proficient we got more profound. Then the question became, What’s the canoe? Well, it’s the Earth, an island floating in a sea of space.”