George Kahumoku Jr.

Maui’s Renaissance man for the Hawaiian Renaissance.

By Peter von Buol with Chris Amundson

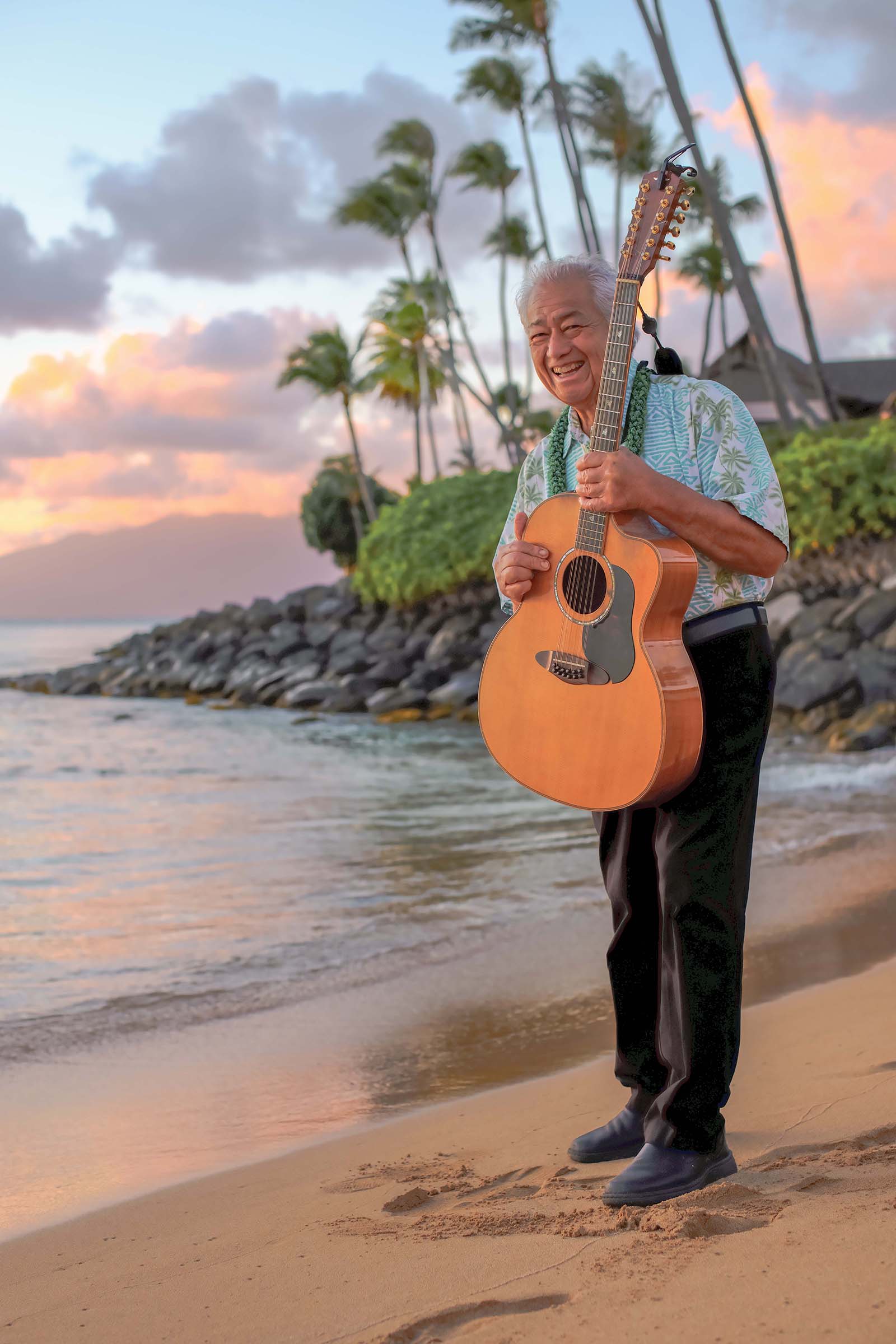

It is a beautiful Wednesday evening at Napili Kai Beach Resort in Napili on Maui’s west side. As the sun is setting over Napili Bay, legendary Maui musician George Kahumoku Jr. is on stage playing his signature 12-string guitar to open his weekly George Kahumoku Jr. Slack Key Show: Masters of Hawaiian Music.

Indeed, Kahumoku is one of the masters. He combines authentically Hawaiian slack key guitar fingerwork with lyrics steeped in Hawaiian heritage. Recently honored with an N Hk Hanohano Lifetime Achievement Award and winner of three Grammy Awards, Kahumoku just returned from traveling the mainland on his annual Masters of Hawaiian Music winter tour. After turning 72 in January, this Maui resident has no plans to slow down.

Now in its 20th year, Kahumoku’s Slack Key Show is one of Hawai‘i’s premier showcases for authentic Hawaiian music. Seated and center stage in Napili Kai, Kahumoku opens the night performing “Kilakila O Haleakal” a classic Hawaiian mele (song) that praises the “majestic” and “beautiful mountain of Maui,” “Glorious Maui, is the very best.”

He picks and strums his 12-string guitar with melodic, rhythmic fingerwork that sounds like three guitars in one – yet again proving he is one of the modern greats of Hawaiian slack key. His deep voice delivers a mele that carries a lifetime of warm memories, a feeling he conveys convincingly during his performance. It’s a song he heard frequently as a child at large family gatherings at his grandparent’s farm on Hawai‘i Island. Kahumoku’s version might seem hauntingly familiar to Maui residents: A few years ago, he recorded a public service announcement advocating for water conservation during times of drought.

That radio spot provides a glimpse of how Kahumoku sees himself – he often reminds friends and family that the root name of “George” means “farmer.” Despite having achieved worldwide acclaim as a musician and composer, in his own mind Kahumoku is a steward of the land. While Kahumoku has earned a shelf full of music awards, he is just as proud of his Hawai‘i 4-H and top U.S. pork producer awards.

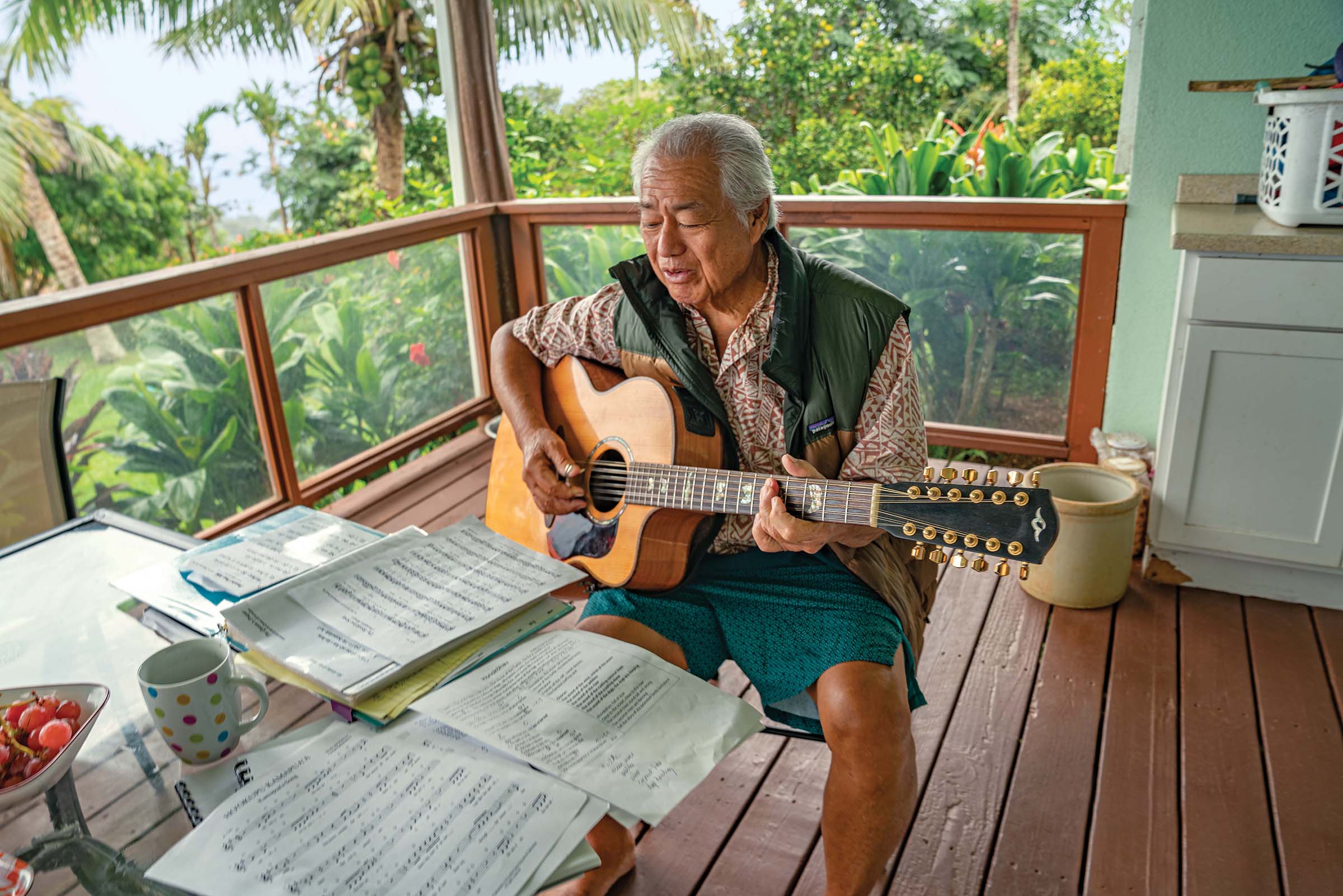

In his younger days, he owned a large beef and hog farm on Hawai‘i Island. Today, Kahumoku still raises crops and livestock on a 2-acre farm in the Cliffs at Kahakuloa agricultural subdivision 8 miles north of Wailuku. Chickens, sheep and miniature horses roam his farm. Fruit trees and traditional canoe plants carried by the original Polynesian settlers dot the farmyard and hillside, including 51 varieties of taro that he plants according to moon cycles.

Each morning, after breakfast on the lanai, he visits the pen of his horses to scoop and redistribute the “fuel that runs the farm.”

“The thing is, I love being on the land and growing things. It’s a big part of my Hawaiian soul,” he said. “Even weeding is a favorite thing that calms me and gives me focus.”

Back at Napili later the same night, Kahumoku performs “Ho‘okupu Kamapua‘a,” a tale of the tumultuous love affair between Tutu Pele, the goddess of fire and volcanoes, and Kamapua‘a, the superhuman hog-man. The hog-man pursues the fire goddess, but the two quarrel and became embroiled in battle. Their fight moves through the chain of Hawaiian islands, creating new land wherever they scuffle. At one point in the mele’s refrain, Kahumoku snorts like a pig – his Napili audience erupts in laughter.

Kahumoku’s DNA and upbringing are steeped in Hawaiian traditions. He traces his musical lineage back to one of Hawai‘i’s first slack key guitarists, George Kuluwaimaka Kaleohano Kauila Mahikoa Kahumoku of Hawai‘i Island. Like the axis deer overpopulation on Maui today, Hawai‘i Island in the 1800s had a cattle problem. Wild cattle introduced during the reign of King Kamehameha I were destroying land, crops and eating roofs off thatched houses.

In the 1830s, King Kamehameha III brought Spanish-speaking vaqueros (cowboys) to Hawai‘i Island and Maui to teach Hawaiians to capture, herd and domesticate the cattle, launching Hawai‘i’s cattle industry. As cowboys are known to do, the vaqueros often played their Spanish guitars and sang songs around the campfire. When they departed Hawai‘i, they also left behind their guitars but hadn’t taught their Hawaiian paniolo (cowboy) students how to play or tune them.

Through trial and error, the paniolo, including Kahumoku’s ancestor, developed their own methods of tuning that slackened or tightened each string to allow for melodic and chordal possibilities that hadn’t existed before in traditional tunings. Each family developed its own ki ho‘alu (loosen the key) tunings – possibly hundreds existed – which were closely-held secrets until the mid-1900s. These tunings, along with the manner the guitars were played, became known as Hawaiian slack key.

The vaqueros were not the only outsiders to influence Hawai‘i in the 1800s. Industrialists and Christian missionaries came. They brought religion, commerce, new types of land use, and influence that threatened to exterminate traditional Hawaiian culture and traditions. As was happening to the native tribes on the mainland, O‘lelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language), hula (dance) and oli (chants, songs and oral histories) were at risk of being snuffed out.

The vaqueros were not the only outsiders to influence Hawai‘i in the 1800s. Industrialists and Christian missionaries came. They brought religion, commerce, new types of land use, and influence that threatened to exterminate traditional Hawaiian culture and traditions. As was happening to the native tribes on the mainland, O‘lelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language), hula (dance) and oli (chants, songs and oral histories) were at risk of being snuffed out.

Though the guitar was of European descent, slack key playing was more closely related to traditional Hawaiian ways. Slack-key remained an underground folk art that incubated virtually unknown to the outside world for a century. Then, Hawaiian music and culture burst onto the world scene at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Within a year, Americans bought more recordings of Hawaiian music than any other genre of music.

However, two other instruments – the steel guitar (a Hawaiian invention) and the ‘ukulele (an adaptation of a Portuguese instrument) – took center stage. Slack key guitarists performed as background accompaniment. Finally in 1946, slack key broke through with a recording by Gabby Pahinui – a haunting version of an old Hawaiian love song “Hi‘ilawe.” Pahinui’s skill demonstrated slack key guitar could become a lead instrument.

Hawai‘i tourism and interest in Hawaiian language and culture increased after World War II. Eventually in the 1960s, the heightened respect for Hawaiian language and culture sparked what became known as the Hawaiian Renaissance.

Many serious musicians eschewed the commercialized steel guitar and ‘ukulele music that was associated Waikiki tourists. They looked to Hawai‘i’s history for inspiration. They found it in slack key guitar, which became a lead instrument of this nascent cultural movement. Through birth, timing and location, Kahumoku was positioned to help lead the Hawaiian Renaissance.

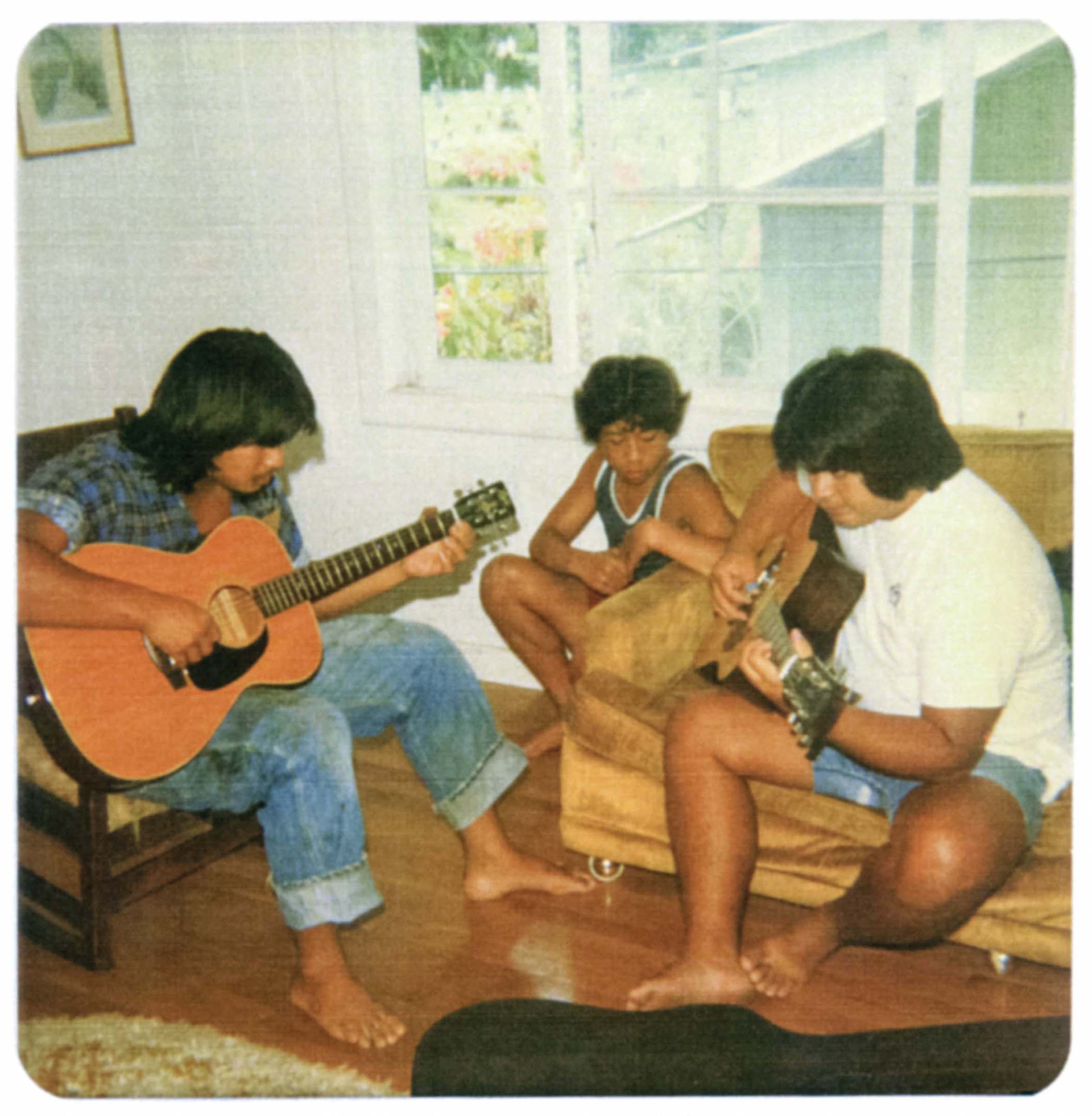

Born in 1951, as a child Kahumoku was immersed in cattle farming, music and Hawaiian mele at his grandparents’ South Kona cattle ranch on Hawai‘i Island. One of six children, Kahumoku was part of a large ‘ohana (family) – grandparents, great-grandparents, aunties, uncles and cousins. Family gatherings were celebrations infused with adults playing musical instruments – especially ‘ukulele and guitar in the slack key style.

After the adults tired for the night, the children would sneak away with the guitars and ‘ukuleles and try their best to imitate what they saw and heard. “Besides me, we had 26 cousins running around like crazy,” Kahumoku said. “The jams would go on for days.” By watching his relatives, Kahumoku learned different methods of playing, including slack key. By the early 1960s, Kahumoku could play one song very well.

When he was five, his parents moved his family to O‘ahu, where his father, George Kahumoku Sr., worked at the city and county sanitation department. Kahumoku attended Kamehameha School-Kapalama Campus and worked a part-time job cleaning cars at Lippy Espinda’s used-car dealership.

On his breaks, he would sit outside and play slack key. The dealership was next door to a strip club. One day, one of the club’s performers approached Kahumoku and asked about his guitar playing. The singer was Kuiokalani (Kui) Lee (soon to become famous for his song “I’ll Remember You”). Lee had quietly noticed Kahumoku’s proficiency on slack key, and though Kahumoku was only a teenager, Lee asked him to play a song at the club.

Later, Kahumoku recalled: “I knew my folks would kill me if they found out.” But he went anyway and played his one song (“Grandpa Willy’s Slack Key”), which took him less than three minutes. The audience went crazy and threw money on stage. Young Kahumoku went outside and counted – $27.10, more than a whole month’s pay of washing cars. He was hooked.

“I knew then I wanted to become a musician,” Kahumoku said. The Kahumoku family’s move from Hawai‘i Island to O‘ahu proved to be key in his musical upbringing. Kamehameha High School nurtured student interest in Hawaiian music and became an incubator for not only Kahumoku, for but many of his classmates who became legendary Hawaiian musicians who helped usher in the Hawaiian Renaissance.

They included: Dennis Kamakahi, Aaron Mahi, Keola Beamer, Jerry Santos, Kalena Silva and Kaniela Akaka Jr.

While Kahumoku enjoyed performing music, he also wanted to pursue a degree in art. After graduation and through the generosity of a trustee at Kamehameha Schools, he attended an art college in California, where he earned degrees in art and education.

Upon college graduation in 1973, he returned home to Hawai‘i Island and worked briefly as a welder (a skill he had learned as an artist). During the summer, he went to Alaska to work on the oil pipeline. After he returned home again, Kamehameha Schools recruited him to be the principal of what was then a small alternative school in South Kona, Hale O Ho‘oponopono. The school’s curriculum emphasized traditional Hawaiian knowledge alongside a Western-style education. Kahumoku also started working with Alu Like, a native Hawaiian social services provider.

By the early 1970s, the Hawaiian Renaissance had fully blossomed with a strong interest in traditional Hawaiian arts and traditions, including music, language, crafts, farming, fishing, hula, history and literature. Having grown up in an extended family connected to the past and present, Kahumoku was well-positioned to make an impact in the Renaissance.

During his early tenure at the school, one of the leading voices of the Hawaiian Renaissance, Winona Kapuailohiamanonokalani Desha Beamer, came to help the new school get off the ground. Working with Kahumoku, she quickly became impressed by his ability to successfully teach both Western and traditional Hawaiian knowledge. Soon, she described him as “Hawai‘i’s Renaissance Man.”

In the mid-1970s, Kahumoku also teamed up with his brother, Moses Kahumoku, to perform evenings at the luxurious Mauna Kea Beach Hotel on Hawai‘i Island. The pair released albums as The Kahumoku Brothers. George and Moses were a perfect match. George was rooted in traditional music, and Moses was interested in jazz and Latin music.

To this day, after their father, George credits Moses as having had the biggest influence on his musical career. During their performances, the pair often would seamlessly interweave their guitars with their different tunings. Playing with Moses introduced George to the minor keys and to frets on the neck of the guitar that were not used by other slack key guitarists.

Due to their authenticity, in 1979 The Kahumoku Brothers accompanied the late Edith K. Kanaka‘ole on her groundbreaking album Hi‘ipoi I Ka ‘Aina Aloha. The album won the 1980 N Hok Hanohano Award for best traditional album. The first track on the album “Ka Uluwehi O Ke Kai,” which featured The Kahumoku Brothers on guitar and background vocals, became an instant classic. Watching Kanaka‘ole write her own songs provided the brothers the impetus to become songwriters.

In the mid-1990s, Hawai‘i’s slack key guitarists gained prominence on the mainland when George Winston, a platinum-selling jazz musician with a major distribution deal for his Dancing Cat Records label, began an ambitious project to record a series of Hawaiian slack key artists on solo and duo acoustic recordings. Winston had fallen in love with slack key years earlier when he had picked up a copy of Gabby Pahinui and Eddie Kamae’s Sons of Hawai‘i’s 1971 Five Faces album.

Winston describes Kahumoku’s music as a “beautiful, vibrant and unique sound” with a “very powerful rhythm, especially with the pull-offs on the guitar, playing and fretting one note, then rapidly pulling the finger off the fretted note to sound the open (unfretted) note on that string.” Winston considers Kahumoku one of Hawai’i’s “most accomplished composers.” Kahumoku has other abilities that make him a terrific stage performer, too.

“He loves sharing the history of the songs, along with playing his own unique and personal interpretations, as well and being a great interpreter of traditional songs and songs by other composers,” Winston said.

As of 2023, Dancing Cat has released 39 recordings in its still-ongoing Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar Masters series. Many did favorably on Billboard’s World Music Chart, and six recordings won N Hk Hanohano Awards for Instrumental Album of the Year.

Kahumoku has also won three Grammy Awards for Best Hawaiian Music album for his work on three compilations albums: Legends of Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar-Live from Maui (2007), Treasures of Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar (2008) and Masters of Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar (2010). He had also co-produced the 2006 winner, Masters of Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar Vol. 1, but due to a clerical error, had not been listed as a producer, a requirement to be awarded a Grammy for a compilation album.

For Kahumoku, the increased exposure from Dancing Cat Records made him an in-demand concert performer. It also brought him into contact with Winston’s sister, Nancy, who had worked for the label. Kahumoku and Nancy fell in love and are now married and living on their farm on Maui.

“Nancy is the heart, body, soul and hands that keep the engine of the business running,” Kahumoku said. She manages the weekly Wednesday evening shows at the Npili Kai Beach Resort. Behind the scenes, she also works the music contracts, licensing, royalty agreements and marketing. Trained as a swing dancer, she switch to hula ‘auana (contemporary hula) and often accompanies her husband on stage.

While there has long been some mainland interest in Hawaiian music, the increased visibility of Dancing Cat Records had made it much easier for the label’s artists to secure bookings. After Dancing Cat released Kahumoku’s Drenched by Music album in 1997, he joined the Masters of Slack Key Festival and has continued to tour mainland cities ever since.

Slack key guitarist David Kahiapo, who has toured with Kahumoku, said there is no better description for Kahumoku than “Hawai‘i’s Renaissance Man.”

“His humble upbringing among many siblings and cousins was in a classic clan ‘ohana style,” Kahiapo said. “He is a very giving man who manages acres of farmland growing fruits, vegetables, and different kinds of animals. He also has a passion for mentoring the next generation and shares the stage with younger, aspiring musicians.”

Among those Kahumoku is currently mentoring is Anthony Pfluke, a 21-year-old Maui-born ‘ukulele and slack key musician. Kahumoku had been impressed with Pfluke’s talent at the 2013 Hula Grill ‘Ukulele Contest. After Pfluke’s success with the 2015 contest, Kahumoku convinced Pfluke to let him teach him slack key guitar. He now performs at shows alongside Kahumoku and shares his thoughts and reflections of his mentor:

“The structure and the way that he operates with a methodical way of living and playing has influenced me,” Pfluke said. “He creates a divine rhythm which really resonates through his music, through his artistry and through his farming and life in general.

“Whether it’s something he’s drawing or something he’s sculpting or a song he’s creating, he has a methodical way of intertwining his thoughts. And he makes these beautiful songs, and when he plays them live, I feel like he invites you into the realm where that song was created.

“Sometimes, it is an incredible realm, such as a song about Tutu Pele. I will be performing on stage with Uncle George, but I am also in this amazing place. He exudes being grounded. This feeling creates a sense of place with his music, and he takes you there every time he plays the songs.”

For Kahumoku, being a musician has provided a platform to sing and talk to audiences all around the world about his aloha for Hawai‘i. His primary philosophy has always been to appreciate what he has been given, and to give back. He mentors young musicians because a future legend, Kui Lee, gave him help at the beginning of his career.

In farming, he follows the philosophy of his grandfather, Willy Kahumoku, who believed one should always add to the layer of soil, not strip it so future generations would have success. As an educator who blends traditional knowledge with Western knowledge, he shows students to appreciate what their ancestors knew and how they can have success in the future.

Click here to subscribe to Maui Nō Ka ‘Oi Magazine