Used in pre-contact Hawai‘i as clothing, bedding, even religious adornment, kapa is made from the bark of the wauke tree, laboriously pounded, then scented and ornamented with extracts of native plants. This craft, like many other native cultural arts, was driven to near extinction after the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. The number of people working today to revive the craft — Denby’s klatch, so to speak — is probably just two to three dozen. Endemic resources are so depleted now that kapa-makers can no longer harvest from the forests. They must grow their own wauke and dye-source plants, and Denby has to contend with deer that invade her yard and scrape their antlers on her living bark supply. On the plus side, she participated in a dramatic moment at the 2011 Merrie Monarch Festival on Hawai‘i Island: she and two-dozen other kapa-makers clothed an entire dance troupe in authentic hula attire for the first time since . . . who knows when. Denby has developed her own kapa style, in dye patterns, symbols and display practices. (Although her pieces are considered art, not functional wear, she won’t seal them behind glass. They must be touched and smelled.) She is finding her way to root her artistic nature deep in the Hawaiian landscape and to keep herself as much as possible outdoors. Rather like you-know-who.

We should note that both mother and daughter are Hawaiian, something between one-half and one-quarter by the math of DNA. Betty Hay’s great-grandmother was half-sister to Princess Ka‘iulani. But Betty Hay and Denby do not regard themselves as cultural practitioners. They see themselves as living forward, not back. “You don’t have to be a kumu [practitioner] to be a Hawaiian,” says Betty Hay. Denby, thinking of both herself and her mother, says, “Landscape is the basis of the culture.”

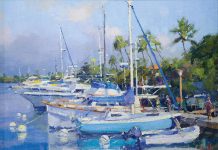

The Sunday interlude ends with Denby walking home, where children ages four and six are waiting. Betty Hay walks from her studio into the main house, which is loaded with paintings, heritage calabashes, feather lei, relics of plantation days, a magnificent antique table that she restored back when she started taking art classes in order to cover the walls, and in every room windows, windows, windows. “Every room opens through windows to the outdoors,” she says. “If you want to kill me, shut me up in a room. Here, I can always see out.”

The Village Galleries carries Betty Hay’s paintings at its venues on Front Street in Lahaina, and The Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua; her work also shows at Viewpoints Gallery in Makawao. Find Denby’s art at Viewpoints, and at Native Intelligence in Wailuku.