Story by Shannon Wianecki

Growing up in the Islands, I’ve learned that whenever I sit down with Hawaiians, I leave a little — or a lot — richer. So when four cultural advisors invited me to listen in on a discussion of their work, I made sure not to arrive empty-handed.

A local farmer provided me with something to show my appreciation: four bundles of pa‘i‘ai, pounded taro lovingly wrapped in ti leaves. I toted them to the Maui Arts & Cultural Center where Hōkūlani Holt, Clifford Nae‘ole, Makalapua Kanuha and Kainoa Horcajo sat talking story in the shade. Four warm smiles let me know that the pa‘i‘ai had been the right choice.

I had some idea of what cultural advisors do, having seen each of these four community leaders in action. Serving as intermediaries between Hawai‘i’s indigenous culture and its visitor industry, they bridge seemingly disparate worlds: ancient/modern, cultural/commercial, sacred/profane, local/tourist. They’re the ones called upon to preside over blessings, open conferences with Hawaiian chants, christen new projects and teach residents and visitors alike what it means to be Hawaiian.

I had some idea of what cultural advisors do, having seen each of these four community leaders in action. Serving as intermediaries between Hawai‘i’s indigenous culture and its visitor industry, they bridge seemingly disparate worlds: ancient/modern, cultural/commercial, sacred/profane, local/tourist. They’re the ones called upon to preside over blessings, open conferences with Hawaiian chants, christen new projects and teach residents and visitors alike what it means to be Hawaiian.

Their jobs didn’t exist four decades ago. If a resort happened to employ someone knowledgeable in Hawaiian arts, he or she was likely relegated to stringing lei with keiki (children) or teaching malihini (newcomers) a few hula moves in the lobby. “Hawaiian themes were not valued as they are now,” says Holt. “They were seen as window dressing, not as a culture that has depth and breadth of knowledge.”

As they talk, I realize that what they do is not just a job to them; it’s a sacred trust — what Nae‘ole calls kuleana, responsibility.

“Kuleana also means privilege,” adds Holt. “We have the privilege of being in places that can affect change, of being able to carry forward the ‘i‘o, the meat, of the culture. With that privilege comes great responsibility, not to ourselves, but to our past and future. We were raised to be non-Hawaiians, to be assimilated into American thinking and lifestyle. But if [what we do] is good for Hawaiians, if it uplifts our culture, then it’s good for everybody who lives in Hawai‘i, no matter where they come from.”

“Kuleana also means privilege,” adds Holt. “We have the privilege of being in places that can affect change, of being able to carry forward the ‘i‘o, the meat, of the culture. With that privilege comes great responsibility, not to ourselves, but to our past and future. We were raised to be non-Hawaiians, to be assimilated into American thinking and lifestyle. But if [what we do] is good for Hawaiians, if it uplifts our culture, then it’s good for everybody who lives in Hawai‘i, no matter where they come from.”

What launched them on this powerful path?

“There’s a Hawaiian term called koho‘ia,” says Holt. “It means ‘chosen.’ You don’t choose. It is koho‘ia, chosen for you.”

“Sometimes you get the calling, but sometimes you get the telling,” says Horcajo to laughs and nods around the table. “And no matter how much you want to say, I’m not ready, it’s not really your call to make.”

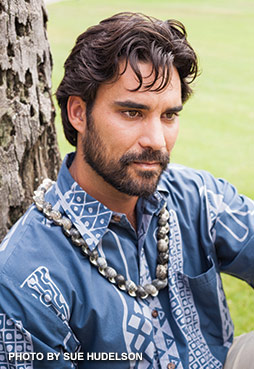

For Horcajo that call came from Kahu Lyons Naone, the man who trained him in lua, the Hawaiian martial arts Horcajo would later teach. “Kahu said, Kainoa, I need you out in Kīpahulu.”

“And the only appropriate answer is, Okay,” laughs Holt.

Of the four, Holt has had the most direct career path. Raised by her grandparents, she was steeped in Hawaiian culture from birth. Holt began teaching hula at age 20 and founded her esteemed hālau (school) in 1976. As the cultural program director for the Maui Arts & Cultural Center, Holt was instrumental in bringing in top-notch Hawaiian performances and facilitated the creation of new works, from Hawaiian-language operas to a groundbreaking exhibit that mixed traditional and modern approaches to making kapa, Hawaiian barkcloth. Today, Holt directs Ka Hikina O Ka Lā, the University of Hawai‘i-Maui

College’s scholarship program for Hawaiian Students.

Nae‘ole found his path later in life. As a young man, he wasn’t interested in taking over his grandfather’s taro farm — his duty as the hiapo, or firstborn — and left Hawai‘i for the mainland. When he returned years later, he found the family’s lo‘i (taro patch) in ruins. The consequences of his choice shook him. After enrolling his son in Hawaiian language immersion school, he felt chastened when he couldn’t help the boy with his homework. “So I started with hula,” he says. “From hula came the root of the language, then came the chant and spirituality, and the doors just busted wide open after that.”

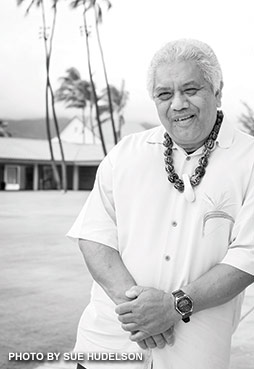

In 1992, Nae‘ole assumed his current role as cultural advisor for The Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua, at a dramatic moment in contemporary Hawaiian history: During the resort’s construction, builders discovered the remains of thousands of Hawaiians buried in the Honokahua sand dunes. Native Hawaiians rallied to protect their ancestors’ iwi (bones), ultimately halting work on the hotel.

“I was serving on the burial council, and that put me on two sides: the council and The Ritz-Carlton,” says Nae‘ole. “I knew that my responsibility was to the kūpuna [elders] and there were times when I had to say to my employer, I’m sorry but this won’t work. You have to abide by these rules. Thankfully, [they] always listened to what I had to say.” The Ritz-Carlton agreed to relocate the hotel farther inland, and the remains were reinterred according to traditional protocols. “Being there, actually putting the iwi back into the earth … that was and is still a very strong emotional attachment for me,” Nae‘ole says.

Over the years, Nae‘ole has educated and advised thousands of employees, guests and visitors. He pioneered a host of educational programs on proper Hawaiian protocol, traditions and mo‘olelo (storytelling). In partnership with The Ritz-Carlton, Nae‘ole offers a weekly Sense of Place video, discussion and walk to the Honokahua preservation site.

Kanuha never imagined she’d be a cultural advisor. The striking chestnut-haired hula dancer planned to sing and dance her way around the world, a goal that she achieved early on. “My turning point was political,” she says. “It was the 100-year anniversary of the overthrow of our queen. That’s when it sparked in my mind: what was I doing for my country or my people? Are my grandkids going to say, How come you never did something?”

When the Westin Kā‘anapali Ocean Resort Villas offered Kanuha a job, her family nearly called a tribal meeting to dissuade her from taking it. “Everybody asked, Why? They’re going to change you,” she says. But Kanuha saw the chance to influence one of the largest resorts in Hawai‘i from the inside out.

“My original position was guest activities director/cultural person,” Kanuha says. “They didn’t have a cultural orientation program for new hires. That’s where I love to be — part of the decision-making, at least by witnessing and saying, Excuse me, why don’t we do it this way? Because this is the proper way to do it.”

After several long consultations with her employer — and a few ultimatums — she transitioned to full-time director of culture, and then became the complex director of culture for the Westin Ocean Resort Villas and the Westin Nanea Ocean Villas. She oversaw the construction of the resorts’ cultural center and regularly teaches Hawaiian language classes.

Listening to them, I’m envious. Like many Americans, I’m culturally adrift. I know next to nothing about my ancestors who hail from various parts of Europe. I can’t imagine what it would feel like to trace my lineage back centuries, identifying the specific people, places and communities that helped form me. To belong to a single community.

But they haven’t had it easy.

The Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s delivered the equivalent of defibrillator shocks to a culture suffering from near-catastrophic injuries. From the time of Western contact in 1778, kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) had endured insult upon injury to their 1,000-year-old traditions. Early missionaries condemned sacred Hawaiian dance as lascivious, while entrepreneurs exported hula skirts as exotic souvenirs. After the overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893, schoolteachers punished Hawaiian children for speaking their native language. Astoundingly, the law forbidding classroom instruction in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i wasn’t repealed until 1986, nearly 100 years later.

Attitudes towards Hawaiian culture have changed — due in no small part to those gathered today. Kanuha, Nae‘ole and Holt belong to the generation on the cusp of the Hawaiian Renaissance. They’ve had to figure out their roles while reassembling their culture and overcoming stereotypes about what it is to be Hawaiian.

Increasingly, Hawai‘i visitors and residents alike crave authenticity; they want to experience full-strength aloha, not a watered-down version. Island executives better recognize the value of incorporating traditional Hawaiian practices and beliefs in the workplace, and many now employ cultural advisors to steer their businesses in the right direction.

Horcajo, the junior member of this esteemed group, represents the next generation of cultural advisors. He, too, was inspired by the commemoration of the queen’s overthrow. He was 11 years old, one of many Hawaiians packed into the War Memorial Stadium in a show of solidarity. “I didn’t know what was going on, but I saw all of these proud people,” he says. “It was an awakening for me.”

He began investigating Hawaiian culture, studied indigenous politics in college and later discovered lua. He’s still very much a student, but has begun to see the impact he can have. Once he helped teach a four-hour class in Hawaiian culture and hospitality for airport security agents. “Afterward, this Hawaiian boy, very local with a beautiful kakau [tattoo] on his arm, came up to me and said, Your class was the first time I ever felt proud to be Hawaiian.” Horcajo was floored.

In 2013, Horcajo brought that native energy to the Andaz Maui at Wailea Resort, where he helped shape the resort’s identity from the ground up, choosing culturally appropriate names for its restaurants and spa and designing educational activities for guests and employees. He then served as Hawaiian cultural ambassador and director of culture for the Grand Wailea Maui Resort, and today owns a cultural consultancy called The Mo‘olelo Group, which focuses on cultural integration and community outreach.

“We’re living in a wonderful time for Hawaiians and Hawaiian culture,” says Holt, her voice humming with optimism. “Our parents thought they had to choose between English and Hawaiian. Today, we know we can have it all. We know that our culture is valuable. It’s valuable to us who live here, and it’s valuable to people elsewhere.”

“Four of my grandsons participated in the Ho‘okuikahi festival [commemorating the founding of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i by Kamehameha the Great],” says Kanuha. “The next generation has got the Hawaiian language, and now they’re seeing kanaka men doing their kuleana. They, too, will learn service, and what it is to be kanaka maoli into this time.”

“Many, many people have come before us,” says Holt. “They’ve laid this foundation of appreciation for Hawaiian culture and the place where we live. Despite all those years of struggling … and many more struggles yet to come … it’s a good time for blossoming. If we can open one mind, if we can influence one decision for the benefit of Hawaiian culture — we live our life for that one.”