Story by Catherine Lo | Photography by Nina Lee

On a quiet Tuesday morning in mid-April, Abraham “Snake” Ah Hee rakes fallen lauhala outside the headquarters of Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua. Mo‘olele, a forty-two-foot Hawaiian sailing canoe, sits on the lawn in front of him, pointed at the shoreline. Behind him, under the corrugated tin roof of the old Lahaina Armory, the pair of hulls belonging to Mo‘okiha O Pi‘ilani rest plaintively on cinder blocks, belying the fact that construction of the ambitious sixty-two-foot voyaging canoe is actually nearing completion.

Ah Hee is a longtime member of Hawai‘i’s voyaging community. He was aboard Hokule‘a, the mother of Hawai‘i’s modern sailing canoes, during its watershed voyage to Tahiti in 1976, and has participated in all of its pan-Pacific journeys since. The success of these long voyages —navigated entirely by traditional wayfinding (guided by stars and sea swells)—lends proof to the theory that ancient mariners capably traversed thousands of nautical miles to settle an incredible expanse of islands. This oceanic migration extended north to Hawai‘i, south to New Zealand, and east to Rapa Nui, ultimately forming the geographic triangle we call Polynesia.

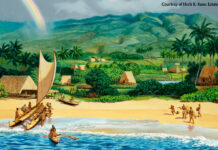

The invention of the voyaging canoe, designed to withstand the most unforgiving stresses of the sea, made Polynesian exploration viable. Primitive boat builders used the natural materials available to them: hardwood trees for the hulls and mast, adze and shells for carving tools, plaited hala leaves for sails, breadfruit sap for caulking, and coconut fibers rolled into sennit for lashing all the parts together. By virtue of the canoes’ masterful construction and the sailors’ extraordinary maritime knowledge, the Hawaiian Islands were populated, and Hawaiian culture given root.

When he was selected to serve on Hokule‘a, Snake didn’t know much about canoe sailing. Like most of his fellow crewmembers—a motley group of paddlers, surfers, and fishermen—he was a resilient waterman who was prepared to endure untold weeks far from land in the middle of the sea. Together, attempting numerous trial runs to and from Moloka‘i, they learned how to sail the remarkable vessel.

By Hokule‘a, Hawaiians found their way home. Its original crewmembers were among a generation who grew up believing it wasn’t okay to be Hawaiian. Western colonization, followed by the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, led to a repression of native culture that lasted through the first half of the twentieth century. During that time, Hawaiians stopped practicing their arts, their religion, their customs, even their language. Traditional knowledge, once passed on through oral history, was lost. When Hokule‘a arrived in Tahiti in 1976, it reawakened Hawaiian culture, showing the world—and Hawaiians—what their ancestors had achieved. The voyaging canoe became the emblem of the Hawaiian Renaissance.

By Hokule‘a, Hawaiians found their way home. Its original crewmembers were among a generation who grew up believing it wasn’t okay to be Hawaiian. Western colonization, followed by the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, led to a repression of native culture that lasted through the first half of the twentieth century. During that time, Hawaiians stopped practicing their arts, their religion, their customs, even their language. Traditional knowledge, once passed on through oral history, was lost. When Hokule‘a arrived in Tahiti in 1976, it reawakened Hawaiian culture, showing the world—and Hawaiians—what their ancestors had achieved. The voyaging canoe became the emblem of the Hawaiian Renaissance.

Hokule‘a inspired Hawaiian communities throughout the Islands to build their own canoes. In 1975, Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua was established on Maui to support the construction of a wa‘a kaulua—a double-hulled canoe. Its name, Mo‘olele, or “Flying Lizard,” recalls the legendary mo‘o (lizard or water spirit) said to inhabit the inland waters surrounding Moku‘ula. The site of that vanished lake and island lies across Front Street from Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua.

For three decades, Mo‘olele has plied the waters around Maui and its neighboring islands, its crab-claw sail fluttering as a visible banner of Hawaiian pride. In 2006, the hui added a thirty-three-foot single-hull canoe, Waipa, to their fleet. These vessels have functioned as living classrooms for Maui’s voyaging community and visitors alike.

It’s the ability of the canoes to teach that anchors the mission of Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua. Building canoes and promoting the spirit of voyaging helps keep traditional knowledge alive, explains Myrna Ah Hee, director of the nonprofit organization and Snake’s wife. Through hands-on experience, students learn about Polynesian voyaging, how the canoe sails, and fundamental values like teamwork, commitment, respect, and conservation that can’t be taught by books.

In 1995, Hawai‘iloa from O‘ahu and Makali‘i from the Big Island joined Hokule‘a and three other voyaging canoes in retracing the ancient sea trail between the Marquesas and Hawai‘i. The expedition prompted Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua to propose its own long-range voyaging canoe that might one day make the same journey of rediscovery. In 1997, the dream of Mo‘okiha O Pi‘ilani, “Sacred Lizard of Maui,” was born.

***

While Snake and Myrna elaborate on Mo‘okiha’s history, Tim Gilliom scurries back and forth, moving tools and materials around the canoe shed. His tall physique is dwarfed by the massive hulls. He is among the second generation of modern canoe voyagers, a fisherman by trade who learned to sail on Mo‘olele thirteen years ago.

Instantly captivated by the voyaging tradition, Tim has clocked thousands of hours aboard Hokule‘a, both in the water and out at dry dock. In the process, he acquired the skills to become a captain, and it’s in this capacity that he serves Mo‘okiha. His voyages on Hokule‘a have taken Gilliom to remote destinations, from tiny atolls in Micronesia to the lush, volcanic islands of the Marquesas. Along the way, under the guidance of first-generation sailors like Snake, he learned the ins and outs of canoe sailing firsthand.

“With the canoe, you always learning,” Snake says. He talks about Mau Piailung, the Micronesian who reintroduced the ancient knowledge of celestial navigation to the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Piailung’s protégé, Nainoa Thompson, became the first modern Hawaiian to master the art. “We would watch Mau, see what he do. If he put his raincoat on, we put our raincoat on,” Snake recalls, explaining how the crew learned to become cognizant of changing wind and water conditions. “Sometimes we would be sleeping and Mau would say we gotta put the sail down. He couldn’t see nothing, but he could sense a squall coming.”

“You have to learn from the bottom up,” he says. “If you’re far from land and something breaks, you better know how to fix it.”

For Snake and Tim, Hokule‘a afforded once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to visit far-flung Pacific islands, but the education wasn’t always glamorous. A voyaging canoe requires an inordinate amount of time and sweat to build and maintain. Gilliom explains that the process includes grasping the function of its architecture and engineering, not to mention the complexities of its rigging. “You have to learn from the bottom up,” he says. “If you’re far from land and something breaks, you better know how to fix it.”

Though Mo‘okiha is being constructed with modern tools and materials like fiberglass and nylon sails, its structural design remains true to the traditional voyaging canoe. There are no screws or nails—the pieces of the canoe are held together by ropes. Also, guiding the canoe from point A to point B cannot be accomplished by pushing a button; voyagers must possess an in-depth understanding of celestial navigation, ocean swells, and weather patterns.

These are lessons Gilliom’s experiences on Hokule‘a have taught him. But what sustains his unwavering devotion is his firm belief in the canoe’s ability to inspire others. “I drop everything for these canoes. I do this because I believe in the canoe. How powerful it is. Who it touches,” Tim insists, laughing about the fact that, since he became involved with Hokule‘a, he’s had four girlfriends and five cars. When Hokule‘a landed on Okinawa, a woman drove half a day from the other side of the island just to present the crew with a painting. People are always bringing tokens of hope and appreciation, he says.

Gilliom is confident that Mo‘okiha will have a similar impact. Realizing it’s now his turn to pass on the knowledge, he is eager to see her ocean-bound. After thirteen years in planning, that day draws near. Last April, some twenty members of Hokule‘a’s crew sailed to Maui and helped sand Mo‘okiha’s hulls in preparation for painting. The mast, sail, and spars have been delivered, and the cedar deck planks will soon be laid.

So far Mo‘okiha has cost more than $700,000 to build. “When you add volunteer hours? It’s been millions,” says Myrna, who credits the generous contribution of nameless volunteers and passersby who stumble onto the project. “One guy built eleven sawhorses,” she says. “The passion is about getting it done.”

So far Mo‘okiha has cost more than $700,000 to build. “When you add volunteer hours? It’s been millions,” says Myrna, who credits the generous contribution of nameless volunteers and passersby who stumble onto the project. “One guy built eleven sawhorses,” she says. “The passion is about getting it done.”

When Hawaiian musician Willie K. was elected president of the hui in 2007, Myrna adds, Mo‘okiha received a much-needed kick-start in donations from benefit concerts he hosted. His commitment is driven by his vision for the canoe: “I want to see her in the water. I want to see her sail into the sunset.”

Myrna keeps her fingers crossed that Mo‘okiha will launch this fall, but it’s hard to predict exactly when. Regarding any timetable, Snake offers a fitting analogy: “Same thing with sailing the canoe. Supposed to be certain place at a certain time, but if no more wind, no can reach.”

***

A group of students from Lahainaluna High School arrives at Kamehameha ‘Iki Park and gathers around Mo‘olele. Practicing Hawaiian protocol, they offer a chant by which they identify themselves and ask permission to approach. Myrna welcomes them to the canoe shed.

As they study the canoe, the teenagers quickly become engaged. “How much does it weigh?” one asks. “Right now, 2,000 pounds—same as Mo‘olele, outside,” Tim replies. “But that’s just the hulls.”

Myrna talks about the hui’s plans to turn the site into a comprehensive cultural education center where visitors can learn not just about voyaging, but about native plants, la‘au lapa‘au (traditional medicine), and the area’s historical significance. Lahaina, she points out, was once the capital of the Hawaiian kingdom.

“The canoe is like an island,” adds Gilliom. “If one lashing over here goes, this whole thing falls apart. If you don’t sustain your island—if you don’t malama ‘aina—the damage trickles down.”

“For me, having a place like this is like having your tools. The canoes are teaching vessels,” Myrna reiterates, nodding toward the students, the future beneficiaries of voyaging knowledge. “They teach people how to take care of each other.

“Everywhere the canoe touches, it awakens the people. [It’s] a revival of their culture.” As she looks up at Mo‘okiha, hope fills Myrna’s eyes. With much pride, she tells the canoe, ‘ohana wa‘a—the canoe’s family—is waiting.