Story by Rita Goldman

This August, the Maui Academy of Performing Arts will stage Miss Saigon in the Castle Theater at the Maui Arts & Cultural Center. Inspired by Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, the play recounts the ill-fated love affair between a young Vietnamese woman and an American GI. A winner of multiple Tony and Drama Desk Awards, Miss Saigon remains, twenty-five years after its debut, one of Broadway’s longest-running shows.

How does an arts organization that began as an after-school program for kids have the chutzpah to mount so ambitious a production — and do so with local actors and musicians, most of whom have

other day jobs? The same way it did last August, with Les Miserables. The big-cast musical ran for six performances on the Castle stage and drew more than 6,000 theatergoers, becoming one of the most successful productions in MAPA’s forty-year history.

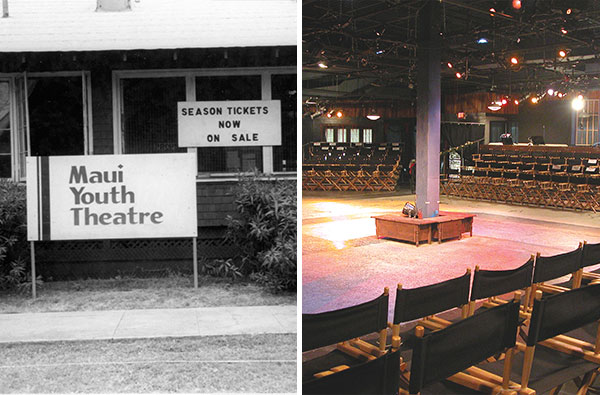

The show’s director, David Johnston, has been MAPA’s artistic director since 1992. In that time, he has faced so many seemingly insurmountable odds that he must feel a particular kinship with the masses who scaled those stage-set barricades in Les Mis. When Johnston moved to Maui in 1990, the organization that would become the Maui Academy of Performing Arts had already been around for sixteen years, long enough for its first participants to grow from little kids to adults. Its founder, Linda Takita, recalled how Jan Dapitan from the county’s Parks & Recreation Department had asked her to use her background in children’s theater to create some activities for the island’s youngsters. Under Takita’s leadership, what began as a six-month pilot program transformed into Maui Youth Theatre. That was in 1974, the same year Takita directed MYT’s first production, The Hobbit, in the old Territorial Building in Kahului.

“It was theater for kids, by kids,” says Johnston. “People like Keali‘i Reichel, Amy [Hanaiali‘i] and Eric Gilliom started at Maui Youth Theatre.” So did Greg Poirier, now a Hollywood screenwriter whose credits include The Lion King II and the ABC TV series Missing, starring Ashley Judd.

Takita created a traveling youth company, called Vagabond Players, and a traveling adult group (known as TAG), which brought classical theater into schools across the Islands. By 1977, Maui Youth Theatre was producing plays featuring adults as well as youngsters. Within a decade of its launch, it was the second-largest nonprofit theater program in Hawai‘i — and even took second place at the 1983 Festival of American Community Theaters in Laguna Beach, California. (Last year alone, MAPA’s classes, camps, and traveling shows reached 38,500 students statewide.)

What makes these achievements even more remarkable is that, for most of its history, the organization hasn’t had a proper home.

In 1980, the county and Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company offered Maui Youth Theatre the old Pu‘unene Clubhouse, next to the A&B Sugar Mill. “It was never a good solution,” says Johnston. “The roof leaked, and it was termite-ridden. Linda remembered rats falling from the ceiling behind her while she was giving the cast their notes . . . having to carry ballerinas across the puddles backstage . . . and the power going off in the middle of performances.”

In 1990, the clubhouse was demolished. The organization moved its classes to Kahului Community Center, its offices, costumes and set construction to the old Maui News building.

That was also the year Maui Youth Theatre changed its name to the Maui Academy of Performing Arts. Although it had long incorporated adult classes and productions, many Mauians continued to think of it as a nice little organization that taught kids to dance and gave them opportunities to act.

“One of our issues, still, is that we’re associated mostly with children,” says Johnston. Then he laughs. “When we did Macbeth, people said how ambitious that play was for kids!”

When Takita left Maui in 1992, MAPA split her job into two positions, hiring David Johnston as artistic director, Francie von Tempsky as managing director.

“The Japanese were investing in Hawai‘i in those days,” Johnston recalls. “Everyone was flush. We would get $100,000 from the state, $75,000 from the county; it allowed for a lot of expansion.”

In 1994, the Maui Arts & Cultural Center opened, and MAPA moved into the McCoy Studio Theater. “Then the Japanese bubble burst, and funding started to shift. Christmas, 1996, we had to lay everyone off, thirteen full-time people. It was down to Francie and me. We moved into a unit in Wailuku Industrial Park, stopped doing community productions, and focused on touring shows to schools and classes in dance and theater. I wasn’t sure the organization would survive.”

One day Johnston got a call from Chris Hart, a consultant who had headed the county’s Human Concerns and Planning Departments.

“Chris was our champion,” says Johnston. “He wanted us to be part of Wailuku, to help revitalize the area. The old National Dollar Store was sitting empty on Main Street. Chris said maybe we could take part of the building. We walked over, stood on the mezzanine, and talked. I said, ‘Chris, I don’t want to share this. It could be a theater, too.’”

With help from then-mayor Linda Lingle, MAPA received a $250,000 grant from the county, obtained a low-interest federal loan, and purchased the building in 1997. Each week, some 500 students attend classes there in drama, singing, ballet, hip-hop and jazz dance. While the kids are in class, parents spend the time frequenting Wailuku’s restaurants and shops.

That the arts can be good for local economies comes as no news to Johnston. He cites a national study by Americans for the Arts, which found that in 2010, despite the recession, nonprofit arts and culture organizations generated $61.1 billion in economic activity, with an additional $74.1 billion in event-related expenditures by their audiences.

“Nonprofit arts and culture organizations are employers, producers, consumers, and key promoters of their cities and regions,” the report stated. “Attendance at arts events generates income for local businesses — restaurants, parking garages, hotels, retail stores.”

Arts organizations even benefit one another. Les Miserables had a $200,000 budget — $75,000 of which went to the Maui Arts & Cultural Center in rental fees and a portion of ticket sales. And becauseLes Mis was a local production, those monies stayed on Maui, a point of pride for Johnston.

That lesson in economics hasn’t been lost on the island’s commercial establishments, either. Autumn Wigley, marketing manager for Maui Mall, notes that foot traffic increases by 250 to 300 people on the one Friday each month that MAPA dancers perform there.

Before Lisa Paulson became executive director of the Maui Hotel & Lodging Association, she headed marketing for Queen Ka‘ahumanu Center. In 2005, she talked with Johnston about having MAPA take over a vacant restaurant on the mall’s upper level, and helped negotiate a lease for what is now Steppingstone Playhouse. That in-house theater not only boosted traffic, says Paulson, “It brought in a demographic we wouldn’t otherwise have — people from Kapalua and Wailea who wouldn’t normally shop here.”

Steppingstone has been a godsend for MAPA, but as the name suggests, it’s a temporary solution. The space is small, maxing out at 158 seats, with difficult acoustics. The logistics of the room necessitate ingenious stagings; a support pole smack-dab in the middle is so obtrusive, it has its own Facebook page.

If David Johnston gets his way, MAPA will have a permanent home before this decade closes. “My dream is a black-box theater similar to the MACC’s, with a capacity of 200 to 300 seats.”

That dream is shared by the county’s Planning Department, which in 2010 hired Brad Segal, president of Denver-based Progressive Urban Management Associates, to come up with a plan for revitalizing downtown Wailuku. His advice? Build on the town’s arts and culture.

“Nationwide, communities are supporting their downtowns more,” says Segal. “Younger people, millennials, want walkable, bikeable urban environments. These are profound demographic and lifestyle shifts.

“We’re seeing a new generation injecting energy into Wailuku. A lot of the boutique stores there are run by people in their twenties and thirties. I think Wailuku is a key to the economic stability and growth of Maui, if [the island] wants to diversify beyond tourism.

“Arts and culture are key components,” Segal adds. “Wailuku could become a thriving attraction for residents. MAPA’s a [major] part of that. What impressed us was not just its programs, but how MAPA is tied to education, to kids and families.”

Erin Wade worked with Segal as a member of the county’s Planning Department, and has made Wailuku’s revitalization her mission. When she says, “We can’t do it without MAPA,” she means it literally.

“The National Endowment for the Arts has a grant program called ‘Our Town’ that requires collaboration of the private and public sectors, and a nonprofit organization.” Wade plans to apply for the grant with Maui County as the public entity, MAPA the nonprofit. As for the private sector, Wade has been talking with the owners of several lots along Church and Vineyard streets where MAPA could build its black-box theater, including that corner location. “It’s the old King Theater site,” says Wade. “Think of the history!”

David Johnston thinks also of the future. “My vision is to develop professional-quality community productions,” he says. “Some people think you start with arts education, and maybe some of the kids will make a living at it someday. I think of it the other way — if kids see excellent productions, they’ll want to be a part of them. Even bigger than our opportunity to have a permanent home, it’s our opportunity to help integrate the arts into our community.”