Story by Shannon Wianecki | Photography by Bryan Berkowitz

Hawai‘i is the most isolated population center on the planet, lying more than 2,200 miles from the nearest continent. Eighty percent of what we consume in the Islands is imported and 98 percent of that arrives by boat. Hawai‘i’s two commercial shipping companies—Pasha Hawai‘i and Matson—serve as lifelines; we rely on them to deliver everything from medical equipment to mandarin oranges to the publication you hold in your hands.

Every two months, a new issue of Maui Nō Ka ‘Oi is printed, trucked to a dock in California, and shipped to Hawai‘i aboard a Pasha vessel. When the editor of Maui Nō Ka ‘Oi asked if I wanted to follow the magazine’s journey across the Pacific, I didn’t hesitate. I’ve dreamt of hitching a ride on a cargo ship since I was a kid. My flight from Maui to San Diego took five hours; the return trip by boat took eight days.

Day 1: Wednesday

At the far end of the San Diego pier, the Jean Anne is easy to spot: ten stories tall and nearly six hundred feet long with “PASHA HAWAII” painted across her broad hull. Jim Marren, the ship’s third mate, welcomes me aboard and gives me a tour of the vessel.

Pasha built the Jean Anne especially to serve Hawai‘i. Named after the founder’s wife, the boat represented a milestone for American shipbuilders: the first pure car/truck carrier built in the nation. While the company’s five other ships carry containers—twenty-by-forty-foot metal boxes that are packed with any and all manner of goods—the Jean Anne is what sailors call a “ro-ro,” a vessel designed to transport roll-on and roll-off cargo. Essentially she functions as a floating garage, capable of carrying 2,500 cars or anything on wheels. Three of her ten decks dedicated to cargo can be raised to accommodate oversized items such as city buses, yachts, and even roller coasters destined for the Hawai‘i State Fair.

I watch the dockworkers drive cars and tractors onto the ship via a one-hundred-ton ramp on the stern. Hotel valets could learn from these speedy, skillful stevedores who pack vehicles in like sardines. The cargo is carefully distributed to maintain balance at sea and every vehicle is lashed down to the deck.

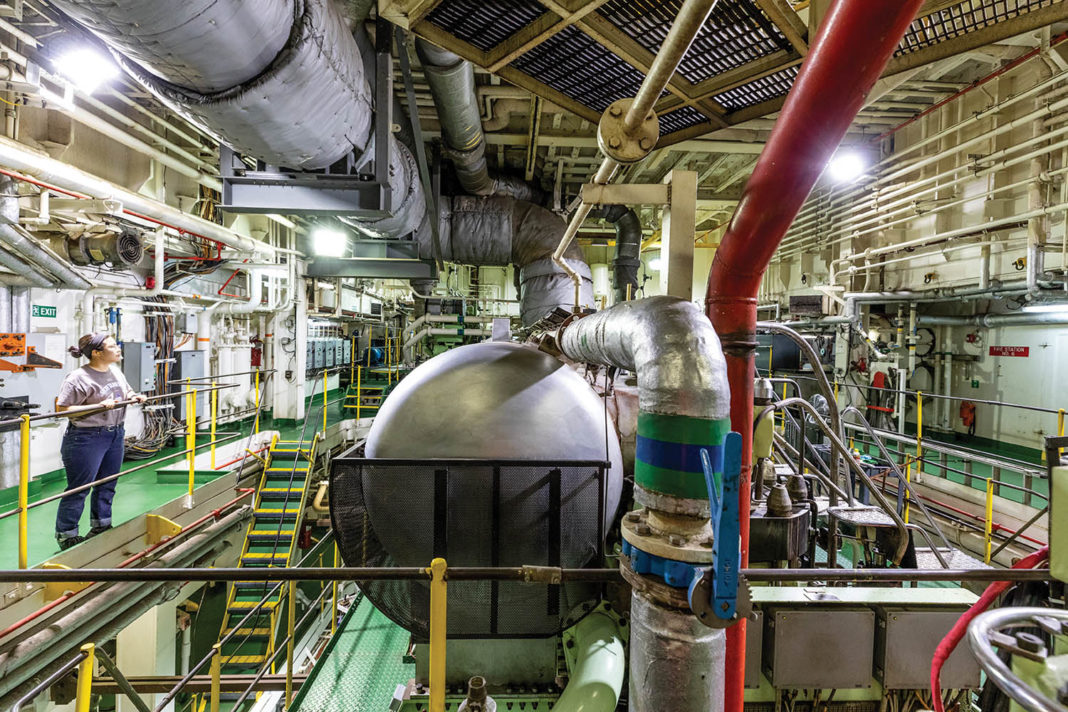

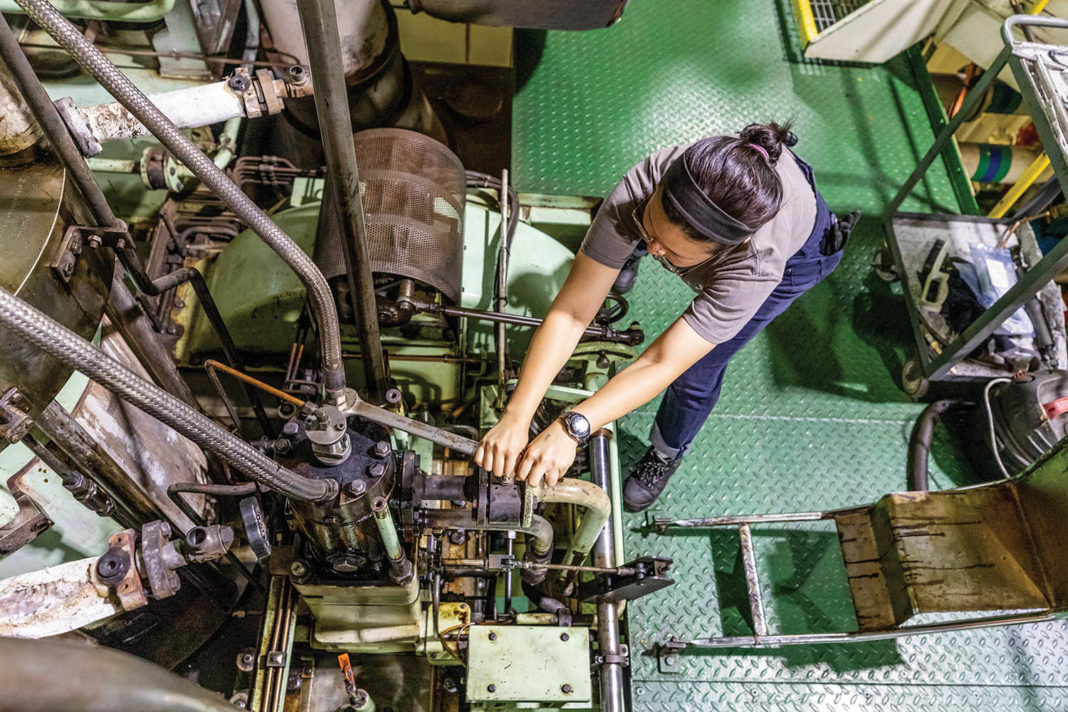

Marren leads me down a metal stairway to the engine room, which occupies the three lowest decks. The roar of the engine is monstrous even when it’s idling; its 14,825 units of horsepower turn Jean Anne’s massive propeller. Next Marren shows me to my cabin—a large stateroom with a tidy bunk, bathroom, and two portholes. Up on the navigation bridge, I meet Captain Steve Bond. The stern but cordial seaman has been with the Jean Anne since the boat launched fourteen years ago. “It’s not as rigid as other ships,” he assures me. “We try to keep it a family atmosphere.” Later, as proof, I hear him practicing guitar in his cabin.

At three p.m., sailors haul the docklines aboard and two tugboats maneuver the Jean Anne off the pier. A harbor pilot joins Captain Bond at the bridge and navigates us safely out to sea. As we pass Point Loma—the last solid ground we’ll see for a week—the pilot prepares to disembark. The crew lets a ladder down the ship’s starboard side to a waiting tug.

Eighteen permanent crewmembers sail aboard the Jean Anne: the captain, three mates, four engineers, several deckhands, two cooks, a bosun, a medic, and an electrician. They work long shifts: seventy days on, seventy days off. After living together for three-plus months, they return to vastly different lives around the globe. Captain Bond lives on a lake in Maine. The chief engineer lives in Sweden. Several sailors are originally from Yemen and the Philippines and now live in Southern California.

Squadrons of pelicans fly alongside the Jean Anne as California fades in our wake. I watch day turn to night from the navigation bridge with Marren. On the horizon I see the silhouette of a single boat. “The captain wants to be alerted if we get within a mile of a ship,” Marren says. “So I make sure he’s never alerted.” With so little traffic in the Pacific, it’s an easy chore.

The heart of any boat is its galley, and that’s especially true on the Jean Anne. Ismael Garayua, the ship’s chef de cuisine, makes all of his sauces and pastries from scratch and regularly prepares special dishes from the crew’s various home countries. My mouth waters at his description of the feast he cooked in honor of Eid, the Muslim holiday. He’s thirty-five years old, from Puerto Rico, and plans to open his own restaurant after a few more years at sea. Tonight he serves tuna steak with wasabi cream, wild rice, and beans, a meal to rival any cruise ship fare.

The traditional naval hierarchy is evident at mealtime. Officers dine in a separate room, able-bodied seamen eat together, and the lone cadet has a whole table to herself: Twenty-three-year-old Kanguen Seo was born in Korea, raised in Turkey, and now attends the Merchant Marine Academy at King’s Point in New York. As the youngest person aboard pursuing a career at sea, this engineer’s apprentice both bucks the stereotype of those who sail these ships and represents the future of the industry. The Jean Anne is her second ship and she loves it.

When I settle into my bunk to sleep, I feel as though I’m lying on the back of a great black horse galloping towards an ever-receding horizon. In the timeless dark my body tenses, anticipating a pause in the movement—but no, the ship lurches on and on carrying me along.