Jason Moore

When I ask Dr. Isabella Abbott, a Hawaiian-plant expert and retired professor of botany and biology from the University of Hawai‘i, what she would most like to teach children about the kukui (candlenut) tree, she responds, “It’s such a joy to see them in the mountains, and I think children would like to know about the lights.”

When I ask Dr. Isabella Abbott, a Hawaiian-plant expert and retired professor of botany and biology from the University of Hawai‘i, what she would most like to teach children about the kukui (candlenut) tree, she responds, “It’s such a joy to see them in the mountains, and I think children would like to know about the lights.”

Any Maui resident knows the beauty Dr. Abbott is talking about: groves of kukui painting distant valleys a silver-green, or lining the hillsides, their branches drawing ink strokes against a Maui twilight. But what’s less-known are the almost innumerable benefits the kukui tree has bestowed on the Hawaiian Islands, as a source of medicine, food, cloth, and canoe products. Even in a society where plants occupy a special sphere of reverence, the kukui has a place of honor, and within Hawaiian culture, no aspect of the kukui is more revered than its role as both a literal and a spiritual source of light.

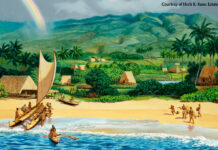

The hardy kukui, or Aleurites moluccana (from “floury,” as in the whitish tint of the leaves’ underside) originated in Malaysia and Indonesia and was spread through Polynesia and southeast Asia as farmers discovered its many uses. The trees may seem to be primeval anchors of the Maui landscape, but it’s generally agreed that kukui, like the ‘ulu (breadfruit), were among the 20 to 50 “canoe plants” whose seeds, roots, and cuttings arrived with the canoes of the Polynesian migration.

The kanaka maoli (original people) knew how valuable the tree could be, and turned the kukui into a virtual botanical factory. Roast or bake the kukui nut, grind it, and mix it in carefully measured doses with Hawaiian salt and limu (seaweed) and you had a relish called “imamona,” still used today, often with chili peppers. As Sig Zane, who has studied native plants extensively for his clothing designs, “That’s what makes the poke so ‘ono.”

Of course, as biologist Art Medeiros warns, the kukui tree contains natural toxins to protect against herbivores, and its products should only be consumed in a very controlled manner. Eat the meat of too many of those tasty nuts, he told me, and you suddenly learn one of their ancient Hawaiian medicinal uses: it’s an excellent laxative. One mashed nut or the sap of the green nut was often used in combination with other traditional medicinal plants for constipation. It was so potent that only experienced practitioners would administer the doses.

The kukui filled many niches of Hawaiian medicine. Dr. Abbott told me that her Hawaiian mother would pull the stem off the green fruit and use the sap that filled up the resultant tiny well as a remedy for a sore throat or sores inside the mouth. Only if that didn’t work would she shrug and say, “better go to the haole doctor.” Other medicinal uses include wrapping heated kukui and noni leaves around rheumatic joints, deep bruises, or wounds and applying baked kukui nut meat and noni fruit to skin ulcers.

This canoe plant was often used to embellish and fortify canoes. Dr. Kawiko Winter, director of the Limo Huli Garden and Preserve, told me that kukui wood was used for the manu, or bird, the removable figurehead of the canoe. Burn the seed and a fine black soot (pau) was produced that could dye kapa (bark cloth) or paint designs on the canoe prow. The inner bark provided a red-brown dye for ‘olona cordage, the outer could provide kapa while the gum from the bark strengthened and helped waterproof the kapa. Perhaps kukui’s most fascinating maritime use was for creating a kind of lens for ocean fishing: chewed kukui nuts spat upon the surface calmed small ripples and increased visibility. One of the most well-known ‘olelo no’eau (proverbs) regarding the kukui is “pupuhi kuku—malino ke kai.” (“when the kukui nut is spat on the water, the sea is smooth”).