Story by Catharine Lo Griffin | Photography by Tony Novak-Clifford

On May 1, 1976, Hōkūle‘a embarked from Maui’s Honolua Bay on her maiden long-distance voyage, bound for Tahiti. It was the first time in 600 years that a Polynesian voyaging canoe—lashed together with six miles of rope and no metal fasteners or screws—had been launched from Hawaiian waters.

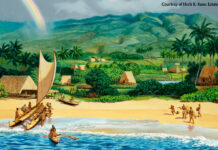

Built by the Polynesian Voyaging Society, Hōkūle‘a’s mission was to retrace the path of seafarers who sailed from Tahiti and other Pacific islands more than a millennium ago, navigating solely by wind, wave and stars. Westerners had long asserted that those early sailors reached Hawai‘i not by celestial navigation, but through sheer luck—how could a “primitive” people find their way without so much as a compass or quadrant? That same assumption of native inferiority gave westerners license to misappropriate the land and disparage Hawaiian culture and the people’s sense of self-worth.

Thirty-one days after her launch, Hōkūle‘a arrived in Tahiti’s capital of Pape‘ete, navigated there without modern instruments. Seventeen-thousand people—three-quarters of the city’s most populated commune—were there to greet her. Her successful journey symbolized the liberation of a culture that had been shackled for more than a century and a half, and confirmed that the Polynesian diaspora across Earth’s vastest ocean had been the deliberate feat of skilled voyagers. It was a watershed moment that reconnected Hawaiians to their ancestral roots and sparked the Hawaiian renaissance.