Story by Shannon Wianecki | Photography by Nina Kuna

Kamapua‘a is a beloved character in many ancient Hawaiian mo‘olelo (stories). The shapeshifting demigod appears alternately as a handsome man, a fierce boar, a slippery humuhumunukunukuapua‘a (pig-nosed triggerfish), a curtain of misty rain, or a lush ‘ama‘u fern. One tale recounts how Kamapua‘a traveled to Kīlauea to woo the volcano goddess. Pele dismissed his advances, crying out, “‘A‘ohe ‘oe kanaka, he pua‘a ‘oe!” (“You are not a man, you are a pig!”) His pride stung, the feisty boar leapt towards the goddess. She hurled fire and molten lava while he summoned torrential rains to douse her flames. After the encounter, Kamapua‘a surrounded Pele’s fiery domain with fields of ferns. Thus the summit of Kīlauea is called Halema‘uma‘u, house of the ‘ama‘u fern.

Ferns such as the ‘ama‘u provide a backdrop for myriad Hawaiian stories—and the foundation for Hawaiian ecosystems. Thanks to its striking colors, the ‘ama‘u is among Hawai‘i’s most recognizable native ferns. New fronds emerge bright red, and mature into shiny green. Synonymous with Halema‘uma‘u, the rainbow-hued beauties can also be found growing trailside at Haleakalā National Park.

Ferns were among the first plants to colonize the Hawaiian archipelago. Many millions of years ago, wind-blown spores crossed the vast Pacific to land on freshly cooled lava, where they nestled into cracks, germinated, and grew. Over countless generations, these pioneer ferns evolved into more than 170 distinct species: some adapted to coastal strands, others to rainforests, and a few to frigid mountain summits. Hawai‘i’s ferns are forest builders. They help break down mineral-rich lava into soil. As they decompose, they create habitat for the next wave of plants: hardy naupaka shrubs and noble ‘ōhi‘a trees.

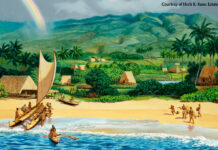

When Polynesian voyagers first made landfall in Hawai‘i, they found islands lush with ferns, the majority of which existed nowhere else on Earth. They cherished these dainty living laces, gave them poetic names, and wove them into stories and daily practices. ‘Ama‘u ferns played many roles in ancient Hawai‘i. Kāhuna (priests) and ali‘i (royalty) walked on paths softened by crushed ‘ama‘u fronds. Builders waterproofed thatched hale (houses) by stuffing ferns into the corners—a practice that continues today at Hale o Keawe, a royal mausoleum in Hōnaunau on Hawai‘i Island. Women used the gummy sap from ‘ama‘u shoots to glue their kapa (barkcloth) together, and other ferns to dye and scent their clothing. Ferns could even serve as weather forecasters, according to Hawaiian historian Mary Kawena Pukui. Her book of proverbs includes this storm warning: Huli ka lau o ka ‘ama‘u i uka, nui ka wai o kahawai. (When the leaves of the ‘ama‘u turn toward the upland, it is a sign of a flood.) In other words, when the wind blows inland, rain is on the way.

so happy to see your article, mahalo