Story by Judy Edwards | Photography by Bryan Berkowitz

The magical hour in which the moon rises has always been a favorite time of day for me. It is a period when linear time and concrete reality feel just a little bit shifted—and that, really, is the point of the full-moon hike I am about to embark on: to bring all of us who are here for the hike into an in-between-ish state of mind.

We are in the Waihe‘e Coastal Dunes & Wetlands Refuge with the man who will guide our hike: Scott Fisher, the associate executive director of conservation for the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust (HILT), the organization that owns this land. There are twenty or so of us, sitting at weathered picnic tables with our backs to the ocean and the wind gusting around us as Fisher speaks. Before we set out, Fisher—an ecologist who also taught a semester of Hawaiian religion at the University of Hawai‘i’s Maui campus—talks with us about the way in which the Hawaiian spiritual perspective breaks the human journey into three parts.

“The ao is the living world,” says Fisher, “the pō is the darkness or afterworld, and the ao kuewa is the wandering land where the ‘uhane, or spirits, become stuck when they are not pono, or ethically right.”

We have come to experience the Refuge during the silvery light of the full moon, and to hear, well, ghost stories… if ghosts can be thought of as those who are suspended, wandering, between the ao and the pō. The bright moon rises, seemingly fighting to get free of the scudding clouds, over the ocean behind us as Fisher continues, “While these two realms—ao and pō—are distinct, they can, and do, cross over at distinct times, including the nights of the full moon, like tonight.”

Our one-and-a-half-mile hike through the Waihe‘e Dune System will take us through gentle, shrubby terrain that is tucked between the beach and the astonishing two-hundred-foot-high dunes that back them. This is a part of Maui—open to strong sea winds and sparsely populated—that is somehow still barely known to the public. Eons ago these spectacular mounds were formed as the reef and beach eroded and blew inland, forming dunes all the way to present-day Kīhei. Humans obliterated many traces of the great Maui dunes, changing the landscape for agriculture, but on this shore the dunes remain, banked up against the foot of the West Maui mountains.

Until the early 1800s an important Hawaiian community thrived here: the village of Kapoho, which was set in the low-lying land between the dunes and the beach. Then for most of the twentieth century the land belonged to a dairy. Milk cows grazed among the village ruins, and weeds thrived in the wetlands and among the tumbled stones of four heiau (temples). When the dairy was put up for sale by Wailuku Sugar, there was a trembling moment during which it nearly became a golf resort. But HILT was able to purchase the land in 2004. The Trust converted it to a 277-acre refuge and has been hard at work caring for and restoring Kapoho ever since.

Fisher is a devout student of the nineteenth-century Hawaiian historian and writer Samuel Kamakau, and this evening he has been braiding together Hawaiian concepts of life and information on the layout of the Kapoho ruins, the history of the dairy, and HILT’s ongoing restoration of the site. He is clearly bursting with much more that he wishes he had time to tell us. “I want you all to know,” he adds as we gather around him and zip our jackets in the cooling air, “that you are always welcome to come here”—by which he means that anyone can visit the Refuge without signing up for a group event.

As we walk, Fisher begins to move the conversation to the mo‘olelo ‘uhane, the stories of the ghosts. When we top a small grassy rise, he says, “We think that Kapoho was possibly founded here around 1425.” That is a lot of time, four hundred years or so, for a great many sad or terrible things to have happened, the usual basis for a ghost story. Fisher insists, however, that, “Many of the ghost stories told here are so positive. And,” he adds, “I have one of my own.” He was camping with his daughter and her friend on this spot years ago, and in the course of the day the kids found some bones in the sand. (Hawaiian commoners were often interred in the sand, and bones wash up even today.) Deep in the night, Fisher heard kids giggling and running around. Exasperated, he got up to call the girls back to bed. Except they were in their tent, sound asleep. Later examination would identify the bones as those of children.

A bit farther down the trail, Fisher gestures to the vague and silvered outlines of the former fishpond area, a structure estimated to occupy about one third of the roughly eighty acres of original wetlands. Volunteers now pull weeds in this area to restore the fresh water flow to the recovering wetlands. One early morning, when Fisher was busy in the Refuge while a lone volunteer was working near the fishpond, the volunteer waved Fisher over to ask who it was that appeared at intervals, silently watching him work. This kind of experience, says Fisher, is “an experience of aloha, is observational.” In other words, some of the elders are still interested in what happens on the land and are not letting death obstruct their sense of responsibility.

Someone asks about the size of Kapoho village. “That is almost impossible to answer, as the commoners moved up and down the slope with the seasons, and the chiefs and their courts moved around the island and islands, but one researcher’s assessment of the population size seems to indicate a capacity of about three hundred,” says Fisher. The community was associated with the Maui high chief Pi‘ilani, and received state visits from the Kamehameha dynastic family. We pause in sight of the light-limned heiau stones. “This is a luakini, or sacrificial, heiau dedicated to Kū”, explains Fisher. “You hear that luakini heiau are the sacrificial heiau, but a better way to think of them is that they were political. We think this one was in its final form by 1802. When Kamehameha II, Liholiho, was four years old, he came here accompanied by his father, Kamehameha I, to consecrate it with an image of the war god Kūka‘ilimoku. They say the entire peleleu war fleet was at anchor along the shore during the ceremony.” History says that the fleet numbered up to eight hundred canoes.

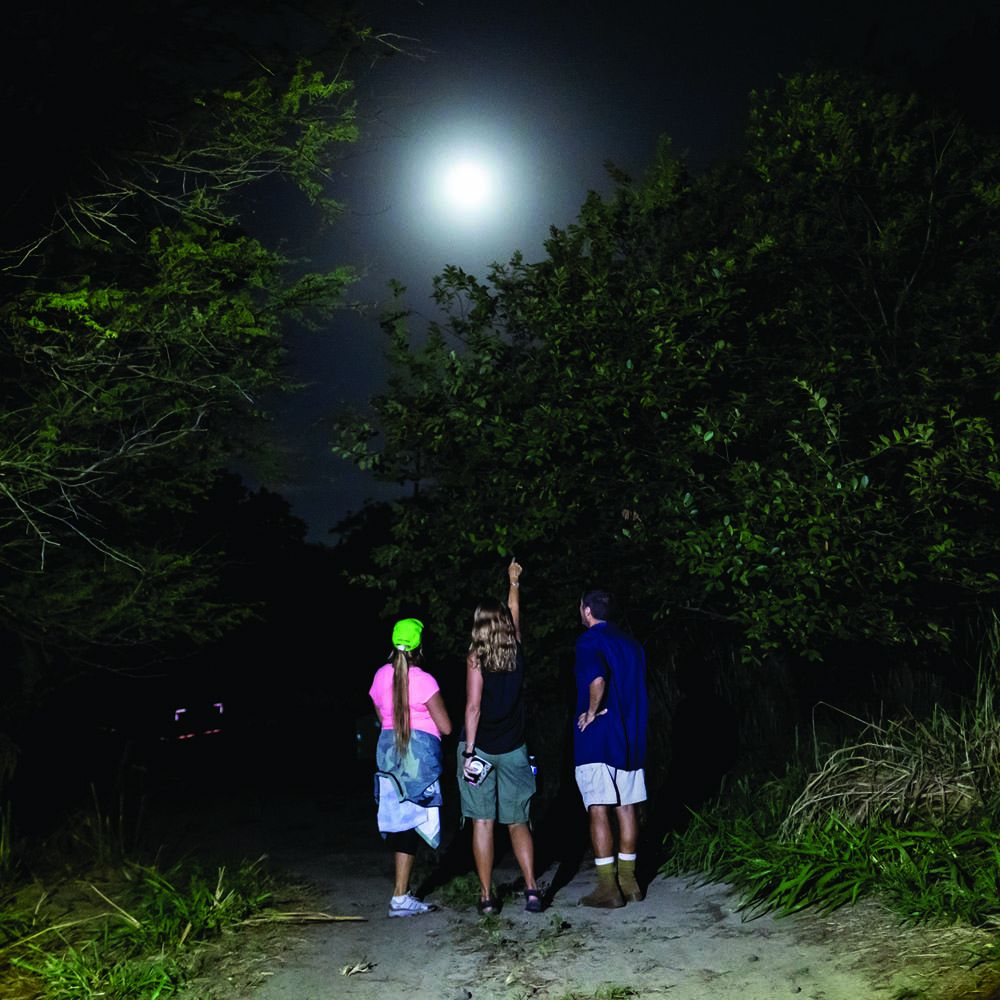

The trail, which has been following the coastline, begins to bend inland towards the dunes. Our group files into a tunnel of trees. Fisher waits while we collect around him. He tells us that we are very near the worker housing of the old dairy. It is much quieter here, and we can hear the tree branches overhead squeak and rub. “The one story that all the dairy workers told us,” he begins, “was about two Filipino bachelors who would, every night, hear tapping on the window of their house. It was driving them crazy. They kept complaining to the dairy manager who finally said he would find a kahuna [Hawaiian priest] to bless the house, though he did not tell the kahuna what the issue was. The kahuna arrived and walked around the house, blessing it, then stopped under the window and said, ‘This is where you hear tapping, yes? There are bones in the ground here, under the window.’ The bones were found and reburied, the house blessed, and the tapping stopped.”

We are a reflective group after that, tramping back with our own thoughts. I ask Fisher a few more questions about his other passion, ecological restoration, and about the school groups that increasingly visit the Refuge. Tonight we have walked just along the shoreline, then inland and back, but there is a longer trail that follows the boundary of the whole Refuge. “I used to run it in the early morning after I opened the Refuge to let the fishermen in,” Fisher tells me. “On those runs, some mornings I used to catch the strong scent of kukui oil lamps, and with it the presence of the kūpuna.”

HILT’s Mission:

The Hawaiian Islands Land Trust (HILT) conserves lands with cultural and historical value, scenic views, agricultural resources, wildlife habitats, water resource areas, and outdoor recreation opportunities. At HILT’s Waihe‘e Coastal Dunes & Wetlands Refuge, active restoration is enhancing critical native wildlife habitat while preserving significant cultural sites.

Moonlight Hike Tip Sheet:

HILT offers a full-moon hike through the Waihe‘e Coastal Dunes & Wetlands Refuge a few times a year. Budget three to four hours for the 1.4-mile round-trip experience, which includes a simple dinner served communally. The wind off the ocean after sunset may be cold; dress in layers. Wear closed-toe shoes that are easy to walk in. The trail is gentle but unpaved and can be either dusty or muddy. Bring water and a flashlight if you have one, though moonlight is the reason for this hike. For further information and to schedule a group for a moonlight hike, contact Scott Fisher at (808) 357-7739 or scott@hilt.org.