Story by Kyle Ellison | Photography by Kyle & Heather Ellison

“I found it!” I yell to my wife, Heather, as we explore abandoned Keomoku village. “I found the Lahaina passenger boat — you’ve got to come check this out!

Covered in yellow kiawe leaves, and protruding from the mud-crusted earth, the boat has sat here, forgotten and splintered, since the middle of the 1920s. Back then, Keomoku village was the hub of life on Lanaʻi, and this boat helped move passengers, packages, and poi across the channel to Maui. Standing in this grove of kiawe today, what amazes me more than the boat itself and its rusty block of an engine, is the fact that it’s sat here for ninety-plus years and is nowhere close to the shore.

It didn’t move; the land did. When the boat was hauled onto the beach in the twenties, its hull lay on the sand. But a century of grazing by introduced deer, sheep and cattle denuded the mountain, and rains brought runoff and sediment, literally creating new land. Three hundred feet of red mud and dirt now separate the boat from the waves.

In the two dozen times I’ve driven this road through Lanaʻi’s rugged “backside,” I’ve never before seen this boat — or even known it existed. Usually when I’m here, driving dirt roads, it’s either to surf or to camp, but today I’m off on a scavenger hunt in search of cultural treasures, using the Lanaʻi Guide, a new app from the Lanaʻi Culture & Heritage Center.

The man behind the recently released app — and the island’s cultural resurgence — is Kepa Maly, executive director of the Lanaʻi Culture & Heritage Center, and the senior vice president of culture of culture and historic preservation for management company Pulama Lanaʻi. Raised on Lanaʻi in a Hawaiian-speaking household, Kepa has spent the past thirty years unearthing Hawai‘i’s stories, translating tens of thousands of pages of Hawaiian archives and oral histories passed down from the kupuna, or elders, who lived them.

To understand the enormity of this project — and the trove of information on the app — you must first understand the vast amount of printed Hawaiian text. The University of Hawai‘i estimates that, between 1834 and 1948, more than 1.5 million pages were printed in Hawaiian newspapers — not counting journals, personal letters, and firsthand accounts. During this time, more published material came out of Hawai‘i than from the rest of the Pacific combined, and since only 2 percent has been translated into English, UH researchers suggest it’s potentially “the largest cache of untranslated historical material in the Western world.

From the Smithsonian to Harvard and back to Lanaʻi, Maly has served as a kind of literary and cultural archaeologist, though instead of searching for artifacts buried in Lanaʻi’s deep red mud, he’s unearthing tales of the island’s past covered up by the sands of time.

“Much of the material in the app,” says Maly, “is sourced out of native-language accounts we’ve translated over the years. We have thousands of native-language and foreign-visitor accounts of Lanaʻi that haven’t seen the light of day since they were written.

That is, until now.

Standing in front of the passenger boat, I scroll down the screen, reading the app on my smartphone, and relay to Heather the story of kupuna Venus Leinaala Gay Holt, who was born in Keomoku in 1905, and regularly rode the boat across the channel to Maui.

“No matter how rough [the water],” she recalled, “Noa Kaopuiki knew how to wait. He would keep the engine running . . . he knew how to count the waves. . . . And all of a sudden, he’d go!

Recalling Holt’s words as I peer out at the waves, I’m struck by how the long-forgotten village comes to life for me. Having just this morning crossed from Maui on the ferry that docks at Manele Bay, I can picture the splash of the boat’s bow cutting quickly and violently through the waves, and feel the sway of the ‘Au‘au current whipped up by the easterly trade winds. I continue scouring Keomoku village, reading one tale after the next. With each successive place the app leads me to, the personal accounts and human touch instill a sense of familiarity with this far-from-empty ghost town.

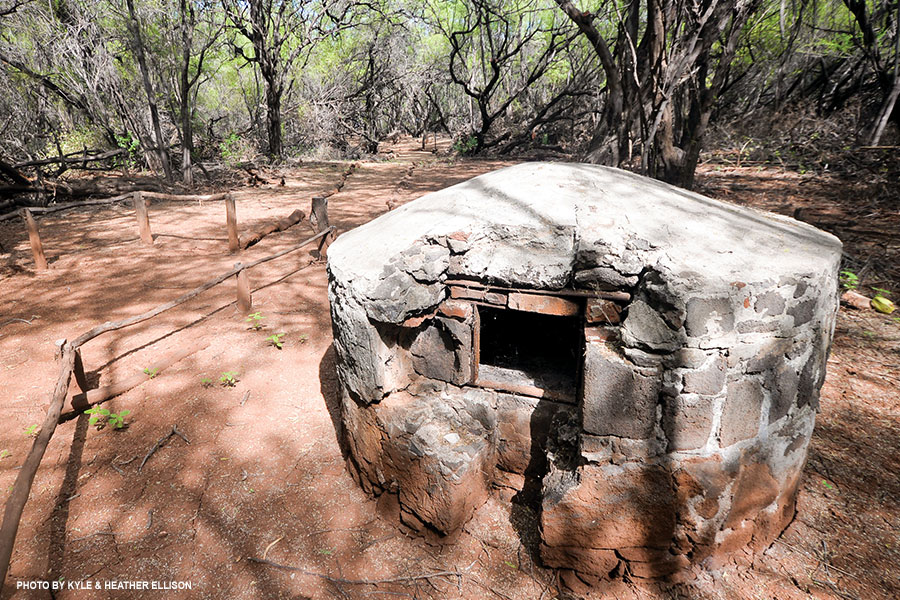

Standing inside hauntingly beautiful but empty Ka Lanakila Church, I imagine the congregation at worship when it was built in 1903, and thanks to the app’s historical photos I can see the church lined with pews. Since the Lanaʻi Guide is GPS enabled and synced with digital maps, I’m told I’m only a quarter of a mile from the Maunalei Sugar Company Mill site. Following a narrow, kiawe-lined trail departing from the back of the church, I emerge at a crumbling, concrete foundation where dreams for the mill once flourished. Reading my screen, I learn it was here where plantation manager W. Stoddert proclaimed in 1899, “The land is proving all that’s promised, and I have no doubt of the substantial returns to the stockholders.

Two years later, in 1901, the operation went bankrupt.

After a ten-minute hike, I find myself giddily glued to my phone and running down the road, wanting to find the next site — and the next — of history hidden in the trees. With the moving blue ball on the screen of my phone instructing me right where to go, I find the abandoned church and schoolhouse by the road in Kahalepalaoa, and the memorial to Japanese laborers, who endured the ocean journey from Japan to toil here in the fields for the reward of seventy-five cents per day. According to the info in my hand, seventy of these workers would die in the span of three years as a result of “various affliction.

Although Keomoku village, Kahalepalaoa, and Maunalei Mill are gone, Maly hopes that these stories of place will ignite an interest in culture, and Lanaʻi can grow as a pu‘uhonua, or sanctuary of cultural resurgence.

“We have a responsibility,” says Maly, “to ensure this history is passed on. And this isn’t just a visitor thing; our kids haven’t been to many of these places. Our people need to be the foremost stewards, because we can’t expect anyone to respect [our culture], if we don’t respect it ourselves.

With the reopening of the renovated Four Seasons Resort Lanaʻi, and the expected revival of tourism, the app is a timely way to explore the roots that have shaped the island’s culture.

“Today’s visitors have evolved,” Maly claims. “For well over a century, tourism in Hawai‘i was sand, sun, surf, sex, mai tais, and the game of golf. There was minimal authenticity. The app’s goal is to provide a meaningful opportunity for people to experience a place unlike anywhere else on Earth. What we have here on Lanaʻi is something nowhere else can offer.

The next day, Maly’s words echo in my head as I park at the Kaunolu shoreline, preparing to explore the Kealia Kapu – Kaunolu Heritage Trail. This heritage complex is also a National Historic Landmark. It was King Kamehameha I’s favorite peacetime fishing ground; his kahua hale, or homesite, is still visible on the bluff, where Halulu heiau towers above the rocky coast. It’s believed Halulu may have been a luakini, or sacrificial heiau. A translated 1868 account from King Kamehameha V says, “Halulu, it is a temple, and place where the bodies of men were placed on the altar, just like a bunch of bananas.

Beneath Pali Kaholo, the massive cliffs that rise vertically a thousand feet above the sea, an epic silence pervades, broken only by the indefatigable waves. It’s humbling enough just to walk here on ground that was home to ancient kings. To read about this exact place, in words first spoken in Hawaiian in 1868 by one of those kings, borders on the surreal. To stand in a place of such cultural import, a setting so untouched, is to feel that Maly might be right — this is unlike anywhere else on Earth.

Late that afternoon, at Manele Harbor, as we wait to cross back to Maui, I whip out the app for a dose of knowledge before the ferry ride home. Apparently, just 100 yards away is an ancient fishing shrine, where submerged springs provided Manele village with fresh water. The remains of a 1920s pipi chute, where cattle were loaded onto boats for transport to O‘ahu, is only a short walk away, as are the Kapiha‘a Fisherman’s Trail and the view of Pu‘upehe islet. Enchanted by the wealth of knowledge in my pocket, available at the tap of a finger, I’m tempted to skip the ferry ride home — stay a little bit longer — and further connect with the island itself, feeling its past brought to life.

If You Go…

GETTING THERE

Expeditions ferries passengers between Lahaina Harbor on Maui and Lanaʻi’s Manele Bay five times a day. Schedule, fees, reservations and other info are at 808-667-3756, Go-Lanai.com. • Your other option is Island Air; the flight between Kahului Airport and Lāna‘i City takes half an hour, and costs $85 round trip. IslandAir.com

GETTING AROUND

Jeeps are available through Dollar Lanaʻi, 808-565-7227, DollarLanai.com; and Lanaʻi Cheap Jeeps, 800-311-6860, LanaiCheapJeeps.com. • Aloha Adventure Rentals offers a Hummer H2; 808-286-9308, AlohaAdventureRentals.com

WHERE TO STAY

Newly reopened, Four Seasons Resort Lanai sits above Hulopo‘e Bay, twenty minutes from Lanaʻi City; rates start at $960. 808-565-2000, FourSeasons.com/Lanai. • Located in Lanaʻi City, Hotel Lanaʻi is a short walk from the town’s restaurants and shops. Rates start at $174, but with only eleven guestrooms, reservations are strongly recommended. 808-565-7211, HotelLanai.com. • The island’s only campground is at Hulopo‘e Beach Park, a five-minute walk from the ferry terminal. Permits are required, and fees apply. Info@LanaiBeachPark.com

WHAT YOU’LL NEED

Basics like food, drink and gas are available for purchase in Lanaʻi City. You’ll need to bring other items with you from Maui: snorkeling equipment, surfboards, camping gear, etc.

The Lānaʻi Guide app was designed and implemented by Maui-based technology firm Koa IT. Visit their website at KoaIT.com.