By Jason Hilford | Photography byJason Moore

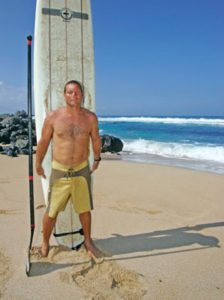

Since April, I’ve probably been gone as much as I’ve been here,” says Dave Kalama. The celebrated waterman is happily back home in Maui, eating a chicken caesar salad—from which he has gingerly picked each and every crouton—and sipping a cold beer on a warm September day at one of his familiar haunts, Charley’s in Pa‘ia.

The Ha‘iku resident has just returned from a seemingly endless stream of worldwide trips centered on surfing, filming, and, most recently, promoting BamMan Productions, the production company he formed with surf buddy/business partner Laird Hamilton and their manager, Jane Kachmer. In fact, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to see a surfing-related medium without images of Kalama, Hamilton, and crew.

Most images depict the men riding monster waves at Pe‘ahi (also known as Jaws) on Maui’s north shore, where this elite group became pioneers of tow-in surfing—using personal watercraft to pull each other into waves too big to catch by simply paddling.

Though well-known and respected on Maui and beyond, Kalama can sometimes take a media backseat to the more vocal and visible Hamilton. And although he has gained international recognition riding those lethal waves, much of the attention overlooks the fact that behind Kalama’s calm and understated persona is a seasoned and well-rounded waterman in the image of the Hawaiians of old.

Thick and dark-featured, Kalama captures the essence of the prototypical watermen, the storied Hawaiians who excelled not only at surfing, but all things aquatic. “Everything I do falls under the category of fun,” explains Kalama, a knowing smile on his face. “Some of it has cultural aspects, some of it has the spiritual, some of it is great exercise, some of it, you get this feeling of accomplishment, but in the end, they’re all pretty fun.”

“I have a pretty fortunate situation,” he continues. “In the end, I get paid to maintain this lifestyle and portray this image that everyone wants to buy into—and it’s not that different from reality. And that’s what’s enabled me to make a living. There’s a little bit of work and effort involved, but the reason I do everything is because it’s fun and it’s good for me and helps everything else I do.”

“I have a pretty fortunate situation,” he continues. “In the end, I get paid to maintain this lifestyle and portray this image that everyone wants to buy into—and it’s not that different from reality. And that’s what’s enabled me to make a living. There’s a little bit of work and effort involved, but the reason I do everything is because it’s fun and it’s good for me and helps everything else I do.”

Half-Hawaiian by blood, Kalama comes from a long line of great Hawaiian watermen, including his grandfather, who brought outrigger canoe paddling to the mainland, and his father Ilima—a lifelong paddler and the 1962 world-champion surfer—who now lives in Pa‘ia.

Somewhat surprisingly, Kalama was born in California—Newport Beach, to be exact. Although he stresses his pride in being Hawaiian, when the subject of his rich ancestry comes up, Kalama is stoic and humble. “When I was young, I knew I was Hawaiian just because my dad was obviously so Hawaiian,” he says. “But I wasn’t really surrounded by it—except for when I was with my Hawaiian cousins. It was never something we sat down and talked about. Plus I was so fair-skinned compared to the rest of them, they kinda treated me like a haole anyway.”

Despite his early exposure to surfing in California when he was a young child, Kalama ironically cemented his water addiction in landlocked Mammoth, California, where he lived during high school—around 200 miles from the nearest ocean. After having learned to windsurf there on a friend’s rig, Kalama received a 10-foot thruster sailboard from his father as a high school graduation present.

“My buddy and I took it down to one of the alkalai ponds in Mammoth,” he narrates. “They’re little half-acre muddy ponds, shoulder-deep or less. On a good windy day, we got it planing [moving steadily across the water]—the first time I’d ever really planed—and it was like [makes angel-singing noise] . . . the sky opened up and the angels sung, and I was like ‘oh my god, this is so fun!’”

In 1985, Kalama, then 20 and in college, was en route to a weeklong family stay on Kaua‘i when the plane stopped at the Kahului airport. One glance at the North Shore’s array of windsurf spots (and screaming trade winds) from the plane was enough reason for Kalama to move to Maui, his ancestral home. Within a few months, he had finished the semester, sold everything he owned, and relocated to the North Shore. After a year, he was a sponsored windsurfer competing at the professional level; he eventually learned to make sails, which he did on the side.

Kalama and friend Brett Lickle first windsurfed Jaws in 1988. In 1992, along with Hamilton and others, they first tried surfing there, using a motorized inflatable boat and boards with footstraps. Kalama still respects his signature spot, to say the least. “That place scares the shit out of me every time I go there,” he admits, an awed hush in his voice. “I don’t care how tough you are—Laird [Hamilton], Hulk Hogan, Mr. T, Clint Eastwood; that wave will do whatever it wants with you. It taught me that no matter how bad things feel, they can always feel worse.”

In recent years, Kalama has added a mildly less life-threatening aquatic pursuit to his repertoire: outrigger canoeing, to which he was introduced unexpectedly a decade ago. His father, who had since moved to Maui, called him one week before the Moloka‘i Hoe, a paddling race from Moloka‘i to O‘ahu, and asked if he’d be part of an all-Kalama team.

“I went, ‘No way, Dad,’” Kalama laughs. “‘I don’t paddle, and I don’t want to let the family down.” Two days before the race, Ilima Kalama called again, this time taking another approach: a fatherly decree. Like a good son (and perhaps half-wondering if he’d have to physically defend himself from his then-52-year-old father otherwise), Dave Kalama relented. “I went over to Moloka‘i, we jumped in the canoe, paddled for about 45 minutes, they showed me how to change in and out, and that was basically it. My next paddling session was out in the channel on the way to O‘ahu.” Once again, he was hooked.

After ten years of almost exclusively paddling a one-man canoe—he was wary of committing to a team situation—Kalama again caved; 2005 was his first season with the Kanaha-based Laeula ‘O Kai paddling club. “It’s turned out to be one of the best things I’ve done in a long time,” he states. “The team thing got me more motivated, sucked me in deeper and deeper. I really enjoy paddling with the other guys and the dynamics of working as a team.”

Kalama gives much credit to his father for shaping him into the man he has become both in and out of the water. “My dad and I have a great relationship,” he says. “It’s almost more like a brotherhood than father and son, although there are times when we need to play those roles. Of course, there were times when I was in high school when I wanted to kill him and [laughing] he probably almost did kill me. In retrospect, he’s largely responsible for who I am, so I wouldn’t change a thing.”