Story by Judy Edwards | Photography by Bob Bangerter

I first saw Nu‘u in 1995, on my birthday. Like so many Hawaiian places, Nu‘u is a specific spot (Nu‘u Landing), a bay, a larger area (Nu‘u is a whole ahupua‘a, or district, of Kaupo) and a descriptor: nu‘u means “height,” and refers to the upswooping, impossible-to-ignore flank of Haleakala that visually dominates this last wild coast of Maui.

I first saw Nu‘u in 1995, on my birthday. Like so many Hawaiian places, Nu‘u is a specific spot (Nu‘u Landing), a bay, a larger area (Nu‘u is a whole ahupua‘a, or district, of Kaupo) and a descriptor: nu‘u means “height,” and refers to the upswooping, impossible-to-ignore flank of Haleakala that visually dominates this last wild coast of Maui.

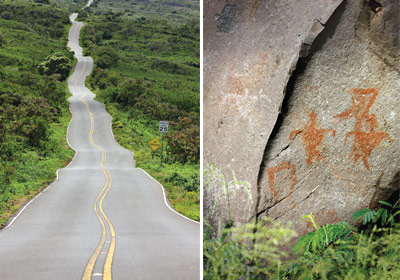

We’d just moved to the island and had not yet driven all the way around it. We splurged on a rental jeep, spent the night in dreamy Hana, and the next morning followed the serpentine road around the corner of the island, past the jungle zone, and into the windswept otherworld of the “back side” of Maui. Jarring and jangling our way along the dirt parts of the road, we came around a bend, parked and stared. I have a photo of myself. My mouth is hanging open. To my left, the dark blue ocean, whipped to froth by the channel winds. Ahead of me, the unfolding leagues of undulating grass and the jagged coastline — boulders, cliffs and arches — and to my right, nu‘u: the heights. If Haleakala’s slope were this extreme above Kihei or Ha‘iku, houses would gradually sliiiiiiiide down over the years, ending at the bottom in a jumble.

And so much space. How is it possible that there was still so much space?

In the ensuing years I have had nothing but questions about Nu‘u, a place that feels like secrets are sleeping. What happened to the people that surely must have lived there? What lies hidden in the folds and cracks of that landscape?

Scott Fisher was the man to ask. He’s the director of conservation for the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust (HILT), and he was raised on Maui, often tagging along with his uncle “Soot,” who was Kaupo Ranch manager from 1968 to about 1982. Scott grew up in this place, absorbing the land into his DNA.

HILT recently acquired, for four million dollars, the eighty-two acres around Nu‘u Landing, another irreplaceable flower in the organization’s lei of refuges that will be available to all, forever. Because the coastal road to reach it deteriorates into a trail beyond ‘Ahihi-Kina‘u Natural Area Reserve, Scott obligingly meets me in Kahului one recent morning and bundles me into his work truck, cheerfully peppering me with questions, answers, musings and stories all the way up the Haleakala Highway through Pukalani, Kula, Keokea, and on through Auwahi, where the great gleaming blades of the eight new white turbines of Auwahi Wind Company are cartwheeling in place against the late-morning sky. A little later, the sight lines open, the long, long coastline comes into view, and Scott pulls over at the twenty-four-mile marker, near the old walls of the first Catholic church on Maui, so I can get out and just look, this time with my mouth closed. He lifts an arm and sights into the distance, where a long, low section of Haleakala’s coast reaches from the skirts of the mountain into the channel. “That’s ‘Ilio Point,” he says, lifting his voice above the wind, “the site of a terrifically important battle when Kamehameha was a young warrior still fighting for Hawai‘i Island. And just this side of it is Apole Point in Nu‘u; that’s where we’re going.”

HILT recently acquired, for four million dollars, the eighty-two acres around Nu‘u Landing, another irreplaceable flower in the organization’s lei of refuges that will be available to all, forever. Because the coastal road to reach it deteriorates into a trail beyond ‘Ahihi-Kina‘u Natural Area Reserve, Scott obligingly meets me in Kahului one recent morning and bundles me into his work truck, cheerfully peppering me with questions, answers, musings and stories all the way up the Haleakala Highway through Pukalani, Kula, Keokea, and on through Auwahi, where the great gleaming blades of the eight new white turbines of Auwahi Wind Company are cartwheeling in place against the late-morning sky. A little later, the sight lines open, the long, long coastline comes into view, and Scott pulls over at the twenty-four-mile marker, near the old walls of the first Catholic church on Maui, so I can get out and just look, this time with my mouth closed. He lifts an arm and sights into the distance, where a long, low section of Haleakala’s coast reaches from the skirts of the mountain into the channel. “That’s ‘Ilio Point,” he says, lifting his voice above the wind, “the site of a terrifically important battle when Kamehameha was a young warrior still fighting for Hawai‘i Island. And just this side of it is Apole Point in Nu‘u; that’s where we’re going.”

Nu‘u, facing Hawai‘i Island across the ‘Alenuihaha Channel, was often caught up in the battles of chiefs and, as the area sandwiched between the ambitions of the highborn on both sides, often the site of invasions. As Scott explains to me the intricate social contortions undergone by the people of Nu‘u to appease both island chiefdoms and not get themselves obliterated, I can’t stop thinking of the African saying: When the elephants fight, the mice tremble.

A few yards past mile marker 31, we pull off the road at the public-access gate leading into the Nu‘u parcel. This gate is always open, easy to find, and no permit is required, but vehicles need good clearance. “Nu‘u is a place where we encourage people to connect with the natural world,” Scott says. “It’s a place were you can easily feel the life of the kupuna [elders]. Time spent here is an opportunity to see not only the past, but our way into the future. Everyone is always welcome.”

We back up onto the road and enter the parcel through a nearby, second gate that leads down to a black-sand beach. Surprisingly, this gate is locked, but anyone can call and ask for the key. Scott says it’s locked to discourage people from driving onto the beach, where monk seals haul out and sea turtles nest — and where huge thorns dropped by kiawe trees have been known to pop tires. “When people call for the key, we explain all that,” he says.

We park the truck and start to walk. Because I am already in my head, planning how often I will come back, I don’t register at first when we stop walking. I am facing a wall of rock maybe twelve feet high, a face of columnar basalt that looks like a giant beaver has scraped downward through stone, leaving tall flat surfaces, elongated sections of grey and faded black. On these surfaces, to my left and right, are petroglyphs: people depicted singly and in groups, arms and legs wide, even apparently . . . dancing? We clamber uphill past them to find ourselves encircled by the remains of ancient walls and standing on the scatterings of the small stones that were once thickly laid here for flooring. Temple? Shrine? Homesite? No one knows, although Thomas K. Maunupau’s book A Visit to Kaupo, Maui, which references a trip he took to the area in 1922, suggests that it was a heiau, or temple, and still in good repair at the time.

We park the truck and start to walk. Because I am already in my head, planning how often I will come back, I don’t register at first when we stop walking. I am facing a wall of rock maybe twelve feet high, a face of columnar basalt that looks like a giant beaver has scraped downward through stone, leaving tall flat surfaces, elongated sections of grey and faded black. On these surfaces, to my left and right, are petroglyphs: people depicted singly and in groups, arms and legs wide, even apparently . . . dancing? We clamber uphill past them to find ourselves encircled by the remains of ancient walls and standing on the scatterings of the small stones that were once thickly laid here for flooring. Temple? Shrine? Homesite? No one knows, although Thomas K. Maunupau’s book A Visit to Kaupo, Maui, which references a trip he took to the area in 1922, suggests that it was a heiau, or temple, and still in good repair at the time.

Not far from this treasure is a breezy meadow where the seasonal structures of residents used to stand. The permanent village of Nu‘u would have been on higher ground, but Hawaiians then and now create temporary homes near the sea when fishing or the season requires it. Scott takes a drink of water and says, “The tsunami of 1946 actually accreted land along this coastline — you can see the difference in the maps—but it ended the time of the last people here. It didn’t destroy the structures so much as it wiped out the road to get down here. It got too hard, and the people left.” He puts the cap on his water bottle, strides over and jumps a fence. I clamber over behind him and walk up to the reason for the fence: the wetland.

It cost $70,000 to fence six acres of wetland to keep the feral pigs and wandering cattle out of it. Every post was dug by hand into rock; Scott’s expression as he describes it convinces me it was horrible work. Every drop of the water here seeps from a spring, that miracle in a dry land. From the air, this must look like an emerald of throbbing life amid rocky, sun-blasted cattle country. Waterbirds define the wetland: endemic Hawaiian coots scoot anxiously back and forth on the surface of the pond while pink-legged Hawaiian stilts take to the air, calling to alert everyone to the presence of two predators, Homo sapiens sapiens, creeping in under the low-slung branches of the kiawe trees that HILT is gradually clearing to open the space and reclaim the wetland. “A lot of ecological restoration is just removing those things that inhibit the recovery of native species, and letting them rebound,” Scott says while he ponders an old pig wallow from the pre-fence days. The stilts settle into the native sedge, makaloa, which is gradually reclaiming its former range. The thing about restoring a wetland on the dry side of an island is that such regions have been the most heavily altered, ecologically. There are almost no examples left of the kind of wetland-in-a-dryland that HILT is working to restore. There is, however, good scientific guessing and a faith that “if you clear it, they will come” back. “It feels good to come here,” Scott says. “I used to come with my parents; now I try to do this with my kids.”

Another fence hop and a short walk down the road brings us to the mile marker 31 gate, and as we go through and head seaward across the peninsula of ‘a‘a (rough, sharp lava) at Apole Point, Scott points to the water-worn stones on which we step, noting that this is a section of the old Hoapili Highway, still used by fishermen today to reach the coast. We divert from the old road to follow the ragged rock boundary at the seaward edge, every now and then stopping to examine the remains of hundreds of ancient temporary structures. It is here that I realize that the crashing, surging, cobalt sea is actually upstaged by the astonishing, majestic slope of the highlands. Whenever we stop, Scott and I unconsciously have our backs to the ocean. There is a reason the people named this area for the heights — they pull on you; you cannot stop looking up-up-up until your sight runs into the bellies of late afternoon clouds.

On the eastern, Kipahulu side of us there is a cliff face on a hill called Pu‘umane‘one‘o that Scott says white-tailed tropicbirds like to frequent. We look for them, but both of us can only notice how eroded the land above the cliff is, how tired and how dry. When there were dryland forests still standing here, was there more water? Was it green more often? Can restoration of the land get us back there?

On the long drive back I absently ask Scott if he dreams. He sits up in the driver’s seat as if I have jabbed him. “It’s so funny you would ask that question,” he says, suddenly animate. “Yesterday I had the most vivid dream. I was looking at the face of Pu‘umane‘one‘o but it was raining, and I was seeing it from the perspective of the ocean. There were white-tailed tropicbirds all over it, on the cliff and in the air, hundreds of them. It was like. . .” his eyes search out mine and then return to the road, “it was like the place was healed.”

If You Go. . . .

- From the Central Valley, the drive to Nu‘u takes about an hour and a half. Call the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust at 808-244-5263 (LAND) to obtain the key, or park nearby and walk.

- DO bring sun protection (hat, sunscreen), closed-toed shoes, food and plenty of water. Nu‘u has no facilities and phone reception is spotty — and it’s a long way from medical attention.

- DON’T climb on arch sites, and please LEAVE DOGS AT HOME; their presence is a major stress to waterbirds.