Stories by Sky Barnhart, Jill Engledow, Chris Hamilton, Paul Wood | Photography by Nina Lee and courtesy of Forest and Kim Starr

One of the pleasures of putting together our environmental issue is getting to recognize a few of the many individuals who are working to make a difference on behalf of these islands. One of the challenges is narrowing that list to five—a feat we only achieved this year by counting as “one” two couples who have woven activism into the fabric of their marriage. Whether their efforts come as part of the job, as volunteers, or a combination of both, Maui is fortunate to have the passion, enthusiasm and insight of environmental heroes like these.

Leading Man

Leading Man

At the start of important meetings, even before he introduces himself, Chris Luedi, Fairmont Kea Lani Maui’s general manager, likes to stand up and chant in Hawaiian.

“Almost immediately I have acceptance, because people understand the importance of perpetuating the Hawaiian culture,” Luedi says.

It’s typical of the way Luedi operates: leading by example rather than by mandate, with a genuine enthusiasm for what he shares. At the Fairmont, Luedi imparts not only his love of Hawaiian culture, but also his passion for the environment.

When Luedi took over as GM in 2001, he put together a “Green Team” of representatives from every department as a base for environmental and sustainable efforts. “It’s a way for all the employees to buy in,” Luedi says.

The idea has worked so well that Maui County has featured the Fairmont in its “Tour de Trash,” a behind-the-scenes look at recycling and waste-processing operations.

To date, the hotel has successfully implemented nearly fifty environmentally friendly initiatives, such as placing recycling bins in guest rooms, treating swimming pools with rock salt instead of chlorine, conducting daily beach cleanups, and recycling laundry water. Green Team members meet every month to ensure the programs continue to grow.

“In the process, we’ve been able to change the attitude of our employees, not only at work but at home,” Luedi says.

More than 500 Fairmont employees have made personal commitments to the environment through Kanu Hawai‘i, a nonprofit organization that encourages individual efforts toward a sustainable Hawai‘i. Fairmont gives everyone who signs up a free tote bag made from recycled materials.

“We’re not forcing them, but encouraging them to make a commitment to take environmentalism to their homes, to replace light bulbs, to use a shopping bag instead of plastic bags,” Luedi says. “The next step is taking this to our guests.”

In 2001, the hotel began placing cards on the beds, asking guests to indicate whether they wanted their linens changed daily or every three days. Recently, Fairmont took it one step further, with cards stating the sheets would be changed every three days to conserve resources.

“We were afraid, but on the contrary, guests actually applauded,” Luedi said. “Ten years ago, it would be unimaginable to think that a guest who spent $2,000 a night wouldn’t get fresh sheets on their bed or new towels every single day. Now green is popular; everybody has an interest in it.”

For Luedi, who was born and raised in Switzerland, environmental concerns have always been a part of life. “In Europe, much is mandated by the government,” he says. “It’s something I grew up with . . . because I spent most of my life outdoors in various adventures.”

With the same zeal he brings to conservation efforts and Hawaiian cultural study, Luedi pursues a wide range of “adventures,” including triathlons, ultra-marathons and long-distance canoe paddling—really long-distance. A founding member of the Hawaiian Outrigger Canoe Voyaging Society, Luedi recently completed a 430-mile journey encircling the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Luedi points to the way the ancient Hawaiians lived in the ahupua‘a system as inspiration. “Sustainable living from the mountains to the ocean is the essence of Hawaiian life, and it’s a great example to talk to our guests about in our Hawaiian cultural tours,” he says. “It all ties together; it’s all one and the same.”

—Sky Barnhar

Stellar Observers

Stellar Observers

While we’re standing in front of the Starrs’ Olinda home, an Anax strenuus passes some ten yards away, looking like a skinny little bird. Kim points, names it. “That’s the endemic dragonfly, the big blue one.” Forest points toward my leg. “You’ve got a Vespula checking you out,” he says. It’s a stocky little wasp hovering near my notepad.

Forest and Kim talk simultaneously, completing each other’s sentences: “The western yellow jacket . . . arrived on Maui in 1980 in a shipment of Christmas trees. . . . They’ve been decimating island insect populations. . . . They cut off the legs and appendages and carry the bodies back to their larvae . . . had an impact on native forest birds.” In twenty seconds I get a ten-minute lesson in the natural history of an invasive species. “We talk at the same time,” says Forest, grinning. “In stereo,” says Kim.

For sixteen years, this duo has made a career out of noticing and compiling scientific data on the plants, bugs, and birds that usually go unnoticed—work that is invaluable to anyone in the state who labors for environmental causes. Last year the Starrs found 300 species of plants in Hawai‘i no one had ever documented.

Snooping around the brackish coastal ponds of leeward East Maui, they spotted a damselfly that had been presumed extinct. Not long ago, they discovered an entirely new species of beetle in, of all places, Kahului, a long-horned wood-boring beetle now known as Plagithmysus kahului. So far it’s only been seen at Kanaha Beach, but Forest and Kim are still looking. That’s what they do—look. When they see something they don’t recognize, they note it and publish the finding. That simple, rare service is their passion.

“We got six new records on Kaua‘i when we were on our honeymoon,” says Forest.

Working with “soft funding” (which means they have no fixed salaries and live from project to project), the Starrs have systematically traveled every road on Maui, using GPS technology to map 120 plant species. They have studied most of the state’s offshore islets. Every year they tally the Haleakala silversword population. They’ve studied ants and done surveys of commercial nurseries.

“We take a picture of every single plant we look at,” says Forest, and these images go on their website, available for free to all. The site (www.hear.org/starr) gets 10,000 views a day.

As volunteer organizers, Forest and Kim have led efforts to save and restore seventy-five acres of coastal dune ecosystem at Kanaha Beach, where they like to surf. But their personal mandate (and profession) is to provide biological information to conservation managers.

The Starrs met while studying at Cornell University, she in hotel school/marketing, he in business. They found their truer natures through rock-climbing, canoeing, and outdoor education. Eventually, Forest brought Kim to Maui, where he was born and raised. Together they trained themselves to be as sharp a pair of naturalists as you’ll find. A true pair.

Forest takes care of the big vision, says Kim; “I take care of the details.” “We work together,” Forest agrees. “It’s our schtick.”

Or true love.

—Paul Wood

Keeping the Coast Clear

Keeping the Coast Clear

It all started with a morning walk. Bob and Lis Richardson, recently retired to Maui from Portland, Oregon, liked to walk the shoreline near Kihei’s Kama‘ole parks. But the path was overgrown, so the Richardsons began to clear the brush.

Nine years later, their casual trail-clearing has turned into a long-running volunteer effort, called Hoaloha‘aina (Friends of the Land), that opened and now maintains the South Maui Coastal Heritage Trail linking Kihei with Wailea. Volunteers remove invasive plants and replace them with natives, help restore dunes and open nesting space for the ‘ua‘u kani, or wedge-tailed shearwater.

Hoaloha‘aina’s first recruits were folks who saw Lis and Bob at work, and offered to help. Then the Richardsons joined forces with the Kihei–Wailea Rotary Club, which had adopted the Kihei Boat Ramp. Now both are Rotary members; Lis is club president this year. Still other volunteers are attracted by regular “Datebook” listings in The Maui News.

Every Monday morning, the Richardsons and their crew spend a couple of hours on the project. One recent Monday, they cleared a view on the point between Kama‘ole II and III by chopping down large invasive shrubs. More important than the view, the Richardsons say, is that removing the invasives would allow native plants to grow. Their deep roots will help hold the dune in place, protecting the ocean from reef-killing runoff.

Down the beach, one volunteer had planted pohuehue, the Hawaiian beach morning glory, with signs directing beachgoers to use paths on either side of the plants. Using marked pathways rather than cutting through beach vegetation prevents erosion and degradation of the dunes.

Having begun near the Kihei Boat Ramp nearly a decade ago, the Richardsons and friends have worked their way a couple of miles north to Kama‘ole I. On one of the first workdays, in 2003, the volunteers filled a forty-foot container with debris from shoreline that had become a drive-through dump and hangout for drug dealers. That stretch of the coast is now a peaceful natural hideaway just yards from busy South Kihei Road; waves splash along rocky cliffs and a mulched trail meanders past burrows left by nesting ‘ua‘u kani and benches installed with funds and labor from the Kihei–Wailea Rotary Club.

The path is edged with coral that had washed up in a big storm. The Richardsons used the coral only after asking Hawaiian cultural expert Kimokeo Kapahulehua if it would be appropriate; he told them that it was a traditional way to mark trails. Careful consultation about the proper procedure is typical; the Richardsons work each step of the way with state and county authorities.

“We expected to hit a bureaucratic wall” when they began reaching out to the government agencies responsible for the shoreline, says Bob Richardson. Instead, the pair say they’ve been amazed and humbled at the respect and cooperation they’ve received from officials. And to their surprise, the Richardsons, who’d never done environmental work before they started clearing a walking trail, are now seen as experts—they’ve been invited to consult with other groups about the best way to restore a coastline and have helped state wildlife biologist Fern Duvall protect and monitor the ‘ua‘u kani.

—Jill Engledow

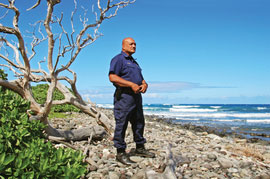

The Enforcer

The Enforcer

Randy Awo doesn’t just attend all manner of meetings related to the environment, the community, and the machinations of government. He presides over them—whether he’s at the front of the room or not.

He doesn’t try to impose himself. He simply exudes leadership.

Awo is Maui branch chief of the Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement (DOCARE) within the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR). That makes him the county’s top environmental enforcement officer—but that’s not why he goes to all those meetings, often volunteering his time to attend. For Awo, malama ‘aina (protecting the land) is a calling.

He was born on O‘ahu and raised on Hawaiian homestead lands in Waimanalo. His grandfather and uncles were fishermen, his father a fish-and-game warden. Those elders were his role models and instilled him with traditional values.

Awo has been with the DLNR for twenty-one years. His “turf” stretches from the tops of Maui County’s mountains to three miles beyond the islands’ shores. His mandate is to enforce regulations—everything from preventing lobster poaching to stopping boating infractions—for the DLNR’s eleven divisions, which include parks, boating, and historic preservation. And he does so with a stretched-thin twenty-three-member team.

“I can’t tell you how many hours [the job] is,” says Awo, “but it definitely isn’t a forty-hour work week. We go wherever the need is.”

Awo gained fame in 2007 when he testified at a state hearing against the Superferry, voicing his concern over its potential as a conduit for the spread of invasive species and theft of natural resources. His stance ran counter to the governor’s steadfast support for the ferry system. No reprimand.

“I definitely felt I might be working at Burger King the next day,” Awo says with a chuckle.

Instead, state legislators gave Awo a prime seat on the Temporary Interisland Ferry Oversight Task Force (the Superferry task force), and his officers conducted vehicle inspections for a year to record natural resources that people were taking from the island.

Despite the broad chest, thick forearms, and a pate tanned from years spent outdoors, Awo speaks softly and has a fair and thoughtful demeanor, say his colleagues and his many admirers —even those who don’t always view state government approvingly.

“I think the world of Randy and all his DOCARE officers,” says Irene Bowie, executive director of Maui Tomorrow. “He has a huge heart, integrity and cares so much about this place. I thank our lucky stars we have him.”

The fact that his team is understaffed and overworked has inspired Awo to help organize public-private partnerships like the Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund‘s Makai Watch program for South Maui’s Ahihi-Kinau Natural Area Reserve. He shares his knowledge with the islands’ young people to recruit them as unofficial protectors.

When Awo, fifty-six, retires from DOCARE in four years, he plans to start his own nonprofit environmental watchdog and lobbying organization.

“As powerful special-interest groups exert economic and political influence over these islands, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the balance between ‘progress’ and environmental protection,” Awo says. “The true wealth of our island state is under constant pressure.

“I think we all share the common ground of wanting to protect the ‘aina,” he says. “This is an honor.”

—Chris Hamilton

The Slim Man

The Slim Man

Alex de Roode has a daunting day job. As executive director of the Sustainable Living Institute of Maui (SLIM), he is charged with helping the island to achieve sustainability in agriculture, renewable energy and local economics.

He is also the institute’s only employee.

De Roode joined SLIM in 2007, two years after the organization was launched as a partnership of Maui Community College (MCC, where SLIM is based), Maui Land & Pineapple Company, Earth University of Costa Rica, and the Royal Technological University of Sweden. His own background includes time spent in academia and on the land, working with traditional farmers in Panama.

De Roode envisions a future in which our isolated island will thrive in harmony with its environment, minimize human impact on natural resources, and preserve those resources for generations to come.

He’s entrepreneurial in his approach, always on the lookout for opportunities to join with others in that mission. Good thing—because his work often overlaps into his free time. One example: He’s a volunteer member of the Maui County Energy Alliance, which was formed after the Maui County Energy Expo in 2007. The alliance expects to recommend plans for a green-power future for the county at a second expo this spring.

Much of his work—on the clock and off—revolves around education. As chairman of the alliance’s Green Workforce Development & Education subcommittee, de Roode helps teachers K–12 develop curricula focused on sustainability, from making their own infrastructure energy-efficient, to teaching kids how to start a garden. He also donates his time to the sustainability committee of his alma mater, Seabury Hall.

An instructor of several of MCC’s “green classes,” which he helped set up, he teaches adults how to lower their energy bills and ecological footprint. And he’s been lead organizer of two major conferences on the MCC campus: the Maui Water Resource Forum in December 2007, and the Island Sustainable Living Expo in August 2008.

“He’s ignited us,” says Lehn Huff, a member of de Roode’s Green Workforce subcommittee. “Alex is a remarkable resource contained in a single human being. He’s focused on what we need for sustainability, and he works hard. His skill is that he can connect people; he’s a champion networker.”

At the base of his commitment to sustainability is a love of nature that began when de Roode was a boy on Maui. Born in Paris, France, he lived here from ages seven to eleven, then returned to attend Seabury Hall. “That connection with Maui and its natural beauty and natural resources really made an impact on me,” he says.

His travels have taught de Roode that people everywhere face similar challenges, and he knows the planet is at a perilous point. But de Roode has hope. “I run into people every day who are involved and really motivated to make Maui sustainable,” he says. “I see a lot of obstacles, bur I rarely see one that can’t be overcome.”

—Jill Engledow