Shannon Wianecki | Painting by Eddie Flotte | Photography courtesy of Anna Palomino

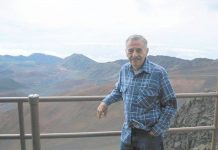

Stoic, wizened, and still full of wonder, Rene Sylva stands in the sunshine at his Pa‘ia Bay home, talking about exploring Hana‘ula with scientific colleagues some 20 years ago. “So cold that day!” He laughs, rubbing his shoulders expressively. He describes leading his friends—the biggest names in Hawaiian botany at the time—into the pristine heart of West Maui, where they discover a native plant, new to science. They later named the species in honor of Sylva, a self-taught botanist whose passion for native plants helped spark a renaissance within Maui’s conservation community.

Stoic, wizened, and still full of wonder, Rene Sylva stands in the sunshine at his Pa‘ia Bay home, talking about exploring Hana‘ula with scientific colleagues some 20 years ago. “So cold that day!” He laughs, rubbing his shoulders expressively. He describes leading his friends—the biggest names in Hawaiian botany at the time—into the pristine heart of West Maui, where they discover a native plant, new to science. They later named the species in honor of Sylva, a self-taught botanist whose passion for native plants helped spark a renaissance within Maui’s conservation community.

Few motorists zooming by recognize one of Hawai‘i’s most respected naturalists as he totes groceries home on Hana Highway, in his uniform white tee shirt and ball cap. Sylva avoids taking any credit himself; he’d rather the plants get all the attention. Talking isn’t easy for him these days; the Hawaiian and Latin names that once rolled off his tongue now come out with some difficulty. But the 78-year-old’s exuberance for endemic and endangered plants hasn’t dimmed one iota. His beachfront yard is a living museum of Hawai‘i’s botanical treasures: A mature lama (ebony) tree guards the gate; luscious white and red abutilon varieties dangle their delicate blooms over the driveway. Real estate in his yard is granted only to the rarest of the rare. Sylva has a soft spot for those plants forced to fight for survival in an increasingly inhospitable world.

Born in January 1929, the lifelong North Shore resident belongs to an older landscape himself. Back when Pa‘ia was a sugar boomtown—population 10,000—his father was the town sheriff. Young Sylva fished for sea turtles. “I have pictures of him throwing nets,” says his long-time friend, Anna Palomino. Like most of Sylva’s friends, Palomino is a key player in Hawaiian conservation herself. Her native plant nursery, Ho‘olawa Farms, is one of the most highly regarded in the state, responsible for supplying critical restoration projects with clean, quality plant stock.

Palomino shows off one of Sylva’s hand-carved tools, a large wooden shuttle used for making turtle nets. He gave it to her when he gave up fishing. “He was a turtle fisherman, but he could see them disappearing,” says Palomino. When a ban on turtle fishing was proposed, Sylva took an unpopular stand, his first of many. He destroyed his nets and gave away his prized shells—the only fisherman who supported the ban. “He said when testimony came up, a lot of fishermen were against him.”

And so the turtle fisher became a gardener of sorts. Recognizing an intimate connection between the health of the ocean and the health of the land, Sylva turned his attention mauka (to the mountains). He explored every peak and valley on Maui. He developed an eye for minute differences in plants from different regions, reporting his findings to preeminent international biologists: Otto Degener and Dr. Harold St. John. When the Maui Zoological and Botanical Gardens opened in Kahului in 1976, he became its caretaker. He personally collected and grew over 200 native coastal and dry-forest species. Gradually he shifted the garden’s emphasis from exotic animals to plants unique to Maui, Moloka‘i, Lana‘i, and Kaho‘olawe—something no one had done before.

“He really started the movement,” says Palomino. “When he [established] the botanical gardens, not many people knew or cared.”

The zoo eventually failed, though the plants thrived, laying the foundation for what is now the Maui Nui Botanical Gardens. When Maui County support of the gardens waned, Sylva organized the Friends of Maui Nui, the seed of today’s Native Hawaiian Plant Society, one of Maui’s most active environmental nonprofit groups. In fact, scratch the surface of any significant conservation effort around Maui County and you’ll likely find this colorful, determined Hawaiian at its root. He initiated the restoration efforts in Honokowai, Kipahulu and ‘Iao Valley, and provided expertise on too many projects to name. Ed Lindsey, collaborator on the Honokowai project and cofounder of Maui Cultural Lands, calls Sylva, “the grand master of native Hawaiian plants.”

“He did some of the first plantings on Kaho‘olawe,” says Palomino. “I remember going to his house and potting up aki aki grass. It’s still one of the most successful plantings over there.” Accepting some credit (where much is due), Sylva agrees. “I planted thousands,” he says.

Not only has Sylva demonstrated a green thumb for rare plants, he’s also found fertile soil in the next generation of conservationists.

“Rene and me are joined at the heart,” says Dr. Art Medeiros, research biologist for the United States Geological Survey. Working with volunteers up at the Auwahi Preserve, Medeiros regularly invokes a Sylva truism: “Mo bettah we do something. We already know what happens when we do nothing.”

“If it weren’t for Rene,” says Palomino, “I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing.” She credits Sylva for inspiring her love and knowledge of native flora. “Days upon days I would be out there with Rene. We hiked all over Maui and he showed me the plants. We’d go out and collect seed. He’d test me; ask me where to find a certain plant. He’s so full of knowledge and so humble at the same time.”

Humble he may be, but this grand master has been a powerful advocate for Hawaiian plants. He doesn’t mince words in an essay published by the Native Hawaiian Plant Society:

“It is a good thing to classify plants as endangered, but we must realize that this does not save them from becoming extinct. It merely gives them paper protection. I recall when the first plant was entered on the endangered species list on April 26, 1978. It is still on that list today. As far as I know, no plant has ever come off the Endangered Species List. The only way for a plant to be removed from that list is to become extinct. To me, this is a disgraceful and insulting way of saving Hawaiian plants.”

“His entire thing is saving the endangered plants,” says Palomino, “because we’re losing so many of them. He’d almost cry when we were out walking because he’d see the destruction from pigs and other invasive species. He’d say he wasn’t coming back to that place again.”

Sylva protested Maui County’s landscaping plans that relied solely on imported—often invasive—plant species. Responding to a proposal for East Maui in 1995, he wrote: “Hana is a very special place. We should be choosy as to what we allow here. It is critically important that we stop the decline of the native forest and begin the turn-around by planting only native species. . . . In the East Maui district there is a better than 50% chance that we can rescue a large portion of the native flora.”

When asked more than a decade later if he still believes this is true—that we can reverse the damage—Sylva nods emphatically. His own work is evidence of what a little perseverance and elbow grease can do. And he’s still at it. He recently joined the fray against the development at La‘au Point on Moloka‘i, arguing for the preservation of the area’s small but precious coastal species. “Nobody cares about the little plants,” he says, shaking his head.

Like the native plants he loves and defends, Sylva is one-of-a-kind, an irreplaceable part of Maui’s landscape. His namesake, tetramolopium sylvae, is a tiny exclamation point of a plant, sporting a wee, daisy-like flower. Despite the threats of grazing cattle, off-road vehicles and aggressive alien species, the plant persists, like Sylva himself.