Story by Rita Goldman | Photography by Cecilia Fernandez Romero

As the truck lurches up the mountain toward Olowalu Cultural Reserve, we’re confronted by the starkness of the landscape and the challenge of the task ahead. Beneath an intemperate sun, grasses leached brown in the arid soil bend before the buffeting wind. Our driver is Al Lagunero, president of the reserve’s board of directors. He stops the vehicle, and we clamber out and stand in respectful silence as he chants in Hawaiian, asking for a lei of wisdom from the ancestors. Then we are off again, rattling slowly along the rock-strewn road.

As the truck lurches up the mountain toward Olowalu Cultural Reserve, we’re confronted by the starkness of the landscape and the challenge of the task ahead. Beneath an intemperate sun, grasses leached brown in the arid soil bend before the buffeting wind. Our driver is Al Lagunero, president of the reserve’s board of directors. He stops the vehicle, and we clamber out and stand in respectful silence as he chants in Hawaiian, asking for a lei of wisdom from the ancestors. Then we are off again, rattling slowly along the rock-strewn road.

Had we sped by, we would have missed the petroglyphs carved into the basanite face of Pu‘u Kilea—anthropomorphic figures that have watched, over centuries, the dramatic changes that occurred here.

Even if we stand still, the soul of Olowalu is largely invisible. But that, too, is changing. A coalition of Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians is bringing life back to this historic valley. What they achieve here could be transformative for the whole island

* * *

Once one of the largest agricultural valleys in West Maui, Olowalu has the dubious distinction of being most famous for a massacre that happened here. In 1790, an American merchant ship lay at anchor off Honua‘ula, along Maui’s southern coast. During the night, natives stole one of the Eleanora’s skiffs, watchman and all. Simon Metcalfe, the Eleanora’s captain, pursued the thieves up the coast to Olowalu, demanding the return of the missing boat and sailor. When all that came back was the boat’s keel and the dead sailor’s thigh bones, Metcalfe lured Olowalu’s inhabitants to paddle out to the ship on the pretence of peaceful trading . . . then opened fire on their canoes, killing more than 100.

Metcalfe meted out more than vengeance against the inhabitants of Olowalu, says Katharine Kama‘ema‘e Smith, a historical novelist who has researched the region extensively. Olowalu was a pu‘u honua, a place of refuge. Commit a crime or displease a chief, and if you could reach a pu‘u honua, not the highest king nor the most powerful warrior could harm you. No wonder the culprits of the Eleanora incident hightailed it to the valley.

“If the massacre at Olowalu is told in the context of pu‘u honua,” says Smith, “Simon Metcalfe unknowingly broke the people’s trust in the concept of sanctuary, and changed how they looked at this area.

“One of our goals is to redeem the purpose of this valley as a sanctuary.”

* * *

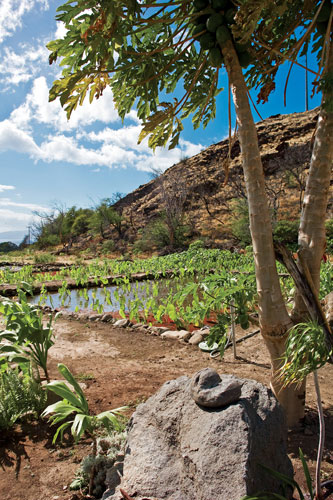

As we climb, the first signs of that transformation appear beside the road: kukui saplings, recently planted and only a few feet tall, but a promise of shade to come. Then the truck crests a plateau into a world of green. Taro leaves nod in greeting, some in red earth, some in lo‘i (paddies) whose water reflects the blue of the sky. Below the lo‘i, someone has planted bananas and sweet potato. Above are the beginnings of a botanical garden of native plants, more than seventy varieties so far, labeled by name and traditional use. Off to one side is a hut where harvested taro can be made into poi.

Smith introduces us to the local topography. That slope forming the valley’s left-hand wall is Lihau, a betrayed wife whom Pele changed into a sacred hill. The Hawaiians considered the leeward sides of the islands female, says Smith. “That’s why this valley was a place of nurture. It had a women’s heiau [temple] and a female chief.”

And not just any female chief. Kalola was the daughter of Kekaulike, ruler of Maui. Her first husband was Kalaniopu‘u, who ruled Hawai‘i Island. Kalola’s granddaughter Keopuolani was so sacred an ali‘i (royal) that the warrior-king Kamehameha sought to capture and wed her to consolidate his authority over all the islands.

In Kalola’s time, and for centuries before, Olowalu boasted a thriving community that enjoyed the bounty of its ahupua‘a, a land division that ran from the mountaintop to the sea. Forests of ‘ohi‘a, koa and sandalwood grew on the valley’s higher elevations, capturing the mist and maintaining the watershed. On its way to the ocean, Olowalu Stream flowed through a sophisticated irrigation system, watering taro, sweet potato and breadfruit, then nurturing the limu (seaweed) that fed fish and people alike. In her booklet Pu‘u Honua: The Legacy of Olowalu, Katherine Smith writes that the valley’s inshore area was a salt marsh that provided habitat for nesting sea birds. Archeological studies of the region have uncovered tools, canoes, and the remains of an inland fishpond.

Then the outside world brought a demand for sandalwood that cleared the upper slopes of trees and weakened the watershed; brought illnesses Hawaiians had no immunity against. In the 1860s, sugar planters started growing cane in the depleted valley, diverting the stream to feed the thirsty crop, and inadvertently changing the coastal habitat. Olowalu became a plantation camp; decades later, a blink-and-you-miss-it stop on the way to the playgrounds of West Maui.

* * *

“We want to restore the ahupua‘a,” says Nani Santos, “to recreate the self-sustaining lifestyle that used to be in old Hawai‘i.”

The reserve’s part-time project coordinator, Santos is an invaluable guide. Through her eyes, you can comprehend what has already been achieved, and what is to come.

Above a pair of wooden bridges that span Olowalu Stream, volunteers have restored two lo‘i that predate Western contact. Below the stream are eleven more, built recently from scratch. “Staff from Old Lahaina Lu‘au started a taro patch here,” says Santos. “Walmart employees built one.”

Almost all the work here—building lo‘i, clearing trails, removing invasive plants and planting native species—is done by volunteers, many of them young. Students from Kamehameha Schools Maui, Hawai‘i Youth Conservation Corps, and Maui Economic Opportunity’s youth division have all pitched in.

One of the most dedicated volunteers is Santos’s father, John Duey, a taro farmer in neighboring ‘Iao Valley.

“Anyone can ‘adopt’ a lo‘i,” says Santos. “My dad will help you start the walls and make sure it’s level enough for water to flow. He brings his tractor to spread the dirt or remove rocks. It doesn’t have to be done only in traditional ways. We don’t charge, and you can keep what you harvest.”

Although a planned culture-and-education hale is at least a year away, Olowalu is already imparting lessons.

“We see lots of middle-school and high-school kids,” says Santos. “When groups come out, we tell the teachers, ‘Have the kids take a walk through the gardens and familiarize themselves with the plants and their uses.’ We want them to become familiar with the way tools and plants were used. Kids are being raised with technology, and have no clue about the past. We tell them, ‘Today no technology: no iPods, no cell phones. You have to immerse yourself.’”

Once a month, Olowalu Cultural Reserve holds a community workday. During February’s, says Santos, “we made almost seventy pounds of poi. We provided poi for a first-birthday lu‘au, and gave some to Olowalu Store. It sold right away.”

That Olowalu is producing the quintessential Hawaiian staple again, after so many generations, is a very big deal to the visionaries behind the cultural reserve. They include Santos’s mother, Rose Marie Duey, who serves as executive director; and until his death in 2009, included Duey’s cousin, Hawaiian conservationist Ed Lindsey. “They saw it as a way to put Hawaiians back on the land,” says Santos, “a way to create opportunities for sustainable living for all of us.”

“The world has conversations now on sustainability,” says Al Lagunero. “We’re looking at cultural sustainability, the return to a meaningful way of life, to creating deeper cultural understandings that can anchor us within the swift global current. That current changes moment to moment; we have to make quicker decisions, yet maintain a sense of mana.

“Mana belongs to everybody,” he adds. “It is what popular jargon calls ‘life force.’ It comes in our food supply, our air; rain puts it into the water supply. We are constantly being held up by this mana, but not everyone knows how to use it. Hawaiian culture teaches you to be conscious of the care of mana.

“What we’re doing here at Olowalu is like arriving again from a great distance.”

Lagunero looks forward to the day when a restored Olowalu Stream flows all the way to the ocean, and the reserve becomes a true ahupua‘a again, its activities and influence extending from the mountain’s summit to the coastal waters, and beyond. “I want us to be able to access the shorelines,” he says. “Families could take their children out at low tide and plant limu, learn how to build holding areas for fish, truly take care of the land mauka to makai, from above to below.

“I’d like to see a repository here for documenting our culture, to restore what’s missing and keep practices alive. We have Bishop Museum in Honolulu, but nothing like that on Maui. A lot of pieces that have been developed by contemporary Hawaiians—new arts, books, paintings, oral histories—have no place to go.”

Lagunero envisions a stone platform built atop the mountain, with terraces for hula and cultural ceremonies. He imagines indigenous people from around the South Pacific arriving at Olowalu ceremonially by canoe, walking up into the reserve, ascending to the platform and being greeted by the people of the region and by an uninterrupted view down the valley to the sea.

Those big dreams are still in the future. For now, Olowalu Cultural Reserve continues to share the land and its wisdom with anyone who wishes to learn—and is willing to get dirty.

For more information on Olowalu Cultural Reserve, call 214-8778 or e-mail lihauolowalu@live.com.