Story by Rita Goldman

In Genesis, God spends the better part of a week shaping Heaven and Earth from the formless void, then stands back and declares that it’s good. He pays an occasional visit, but long before the Old Testament ends, God drops out of sight, a distant figure detached from His own creation.

In Genesis, God spends the better part of a week shaping Heaven and Earth from the formless void, then stands back and declares that it’s good. He pays an occasional visit, but long before the Old Testament ends, God drops out of sight, a distant figure detached from His own creation.

Hawaiians first encountering this western cosmology must have found it bewildering. In the worldview inherited from their ancestors, the divine is everywhere, and everything is the divine.

One term for this concept, kino lau, translates literally as “many bodies,” the myriad forms of the 400,000 gods that make up the Hawaiian pantheon. Every plant and animal is an embodiment of a god. So are clouds, rain, the movement of lava, the currents of ocean and air.

“There is some connection between the characteristics of the god and the kino lau,” says Hokulani Holt, a Hawaiian cultural expert and revered kumu hula (teacher of hula). She offers the example of Kāne, who, along with Kū, Kanaloa and Lono, is one of the four main Hawaiian gods. Because Kāne’s realm includes flowing and upwelling water, says Holt, “many of his kino lau are either water bearers or plants that need lots of water: taro, bamboo, awa. . . .”

I ask whether the shark is a kino lau of Kū because both are aggressors.

“When Kū is the god of war, the shark is one of his forms, yes,” Holt replies. “But kino lau are complex, because the god, too, has many forms.”

To illustrate, she recalls a question I had asked upon learning that each of the four principal gods is paired with a goddess. I had wondered why Lono, god of peace and agriculture, would be linked with Pele, goddess of volcanoes.

“Lono is not the god of peace and agriculture when he is with Pele,” Holt explains. “He is Lono-makua, the fire god. When he is the god of peace and agriculture, he is linked to Laka, goddess of hula. That’s why at Makahiki, the time of Lono, there is always hula.”

This divine mutability begins to explain how the Hawaiians have 4 gods, but also 40, and 400, and 400,000. Kino lau, it turns out, is a deceptively simple term for the rich and complex relationship between Hawaiians and the rest of the natural world.

Asked for an example of how one might interact with the gods through kino lau, Holt chooses what she knows best: hula.

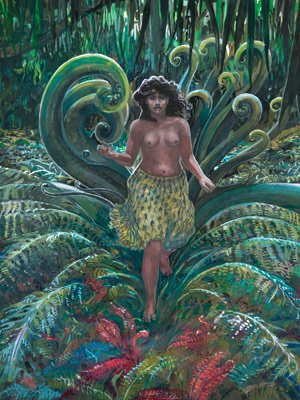

“Among the kino lau of Laka, the plants ʻōhiʻa lehua, ʻieʻie, hala pepe, maile, palapalai and other native ferns usually have the highest status. In addition, many hālau [hula schools] have particular native plants special to them. My hālau is Pāʻū O Hi‘iaka. Hi‘iaka, this particular one, is Pele’s youngest sister, Hi‘iakakapoliopele. Pāʻū-o-hi‘iaka is also the name of a beach vine. The plant holds higher status in our hālau than it might in others.”

“Among the kino lau of Laka, the plants ʻōhiʻa lehua, ʻieʻie, hala pepe, maile, palapalai and other native ferns usually have the highest status. In addition, many hālau [hula schools] have particular native plants special to them. My hālau is Pāʻū O Hi‘iaka. Hi‘iaka, this particular one, is Pele’s youngest sister, Hi‘iakakapoliopele. Pāʻū-o-hi‘iaka is also the name of a beach vine. The plant holds higher status in our hālau than it might in others.”

When non-Hawaiians came to power in the Islands, hula was relegated to mere entertainment —when it wasn’t prohibited outright. But hula is more appropriately comprehended as a spiritual practice. Before the dancers perform, they gather kino lau, plant forms of Laka, to adorn themselves and the hula altar.

“Many hula people conceive of three hula altars,” says Holt. “The first and most important is the mountain. The second is the altar that exists within a hālau hula, a hula school. The third altar is the dancers themselves.”

Because the dancers will become Laka, the essence of hula, there’s another step that precedes the gathering of kino lau.

“Beyond making sure that the dancers are well prepared in their dance,” says Holt, “I expect an understanding of the story being told, the poetry.” If plants are physical forms that connect one to the divine, “poetry is an intellectual connection to the kino lau. The statement I always give to my hālau is: Dance the poetry, not the choreography.

“Let’s say we’re doing ‘Aia La O Pele,’ a well-known chant that describes what happens during an eruption. The second verse says, ‘uhi uha,’ a munching and crunching sound that occurs as the lava moves through the ground and the trees. The lava is the kino lau, but we also know that the lava is Pele, munching and crunching through the land. The sound is her. The dancers incorporate Pele when they dance that verse.

“When the dancers are prepared appropriately, that’s when the plant forms come into play. Because I have a great concern over gathering endangered species in the wild, I do not on a regular basis take the dancers to the mountain to gather the plants,” Holt adds. “I teach them to make lei from other plants that are acceptable. I have taught my lead dancers, my alakaʻi, how to gather, and if needed, they go to the mountain.”

The concept of kino lau encompasses more than rituals and religious belief. It’s a way of being in the world that enabled Hawaiians to thrive on these remote and isolated islands for more than a thousand years. Compare that to two centuries of the unsustainable practices that usurped Hawaiian traditions: The state leads the nation in endangered and extinct native species; and without imported goods, could support a population comparable to that of pre-Contact Hawai‘i for about a week.

The concept of kino lau encompasses more than rituals and religious belief. It’s a way of being in the world that enabled Hawaiians to thrive on these remote and isolated islands for more than a thousand years. Compare that to two centuries of the unsustainable practices that usurped Hawaiian traditions: The state leads the nation in endangered and extinct native species; and without imported goods, could support a population comparable to that of pre-Contact Hawai‘i for about a week.

“Our ancient kūpuna [elders] were aware of the need to be respectful of the environment,” says Holt. “Agrarian societies cannot survive if they don’t know every nuance of the environment: soil, plant cycles, wind. . . .” One way to perceive these nuances is as kino lau.

“In the relationship between the Hawaiian and his environment, things were not all bad or all good. They had both, just like us. Some might think that the shark is bad because of his predatory nature, but the good he provides is the balance within the ocean. Thus, the aliʻi [chief] was also seen as a shark on the land; hopefully, when what he does is done well, he achieves the same thing.”

Before our conversation ends, I ask Holt for an example of kino lau unrelated to hula. The question gives her a moment’s pause. In traditional society, she explains, “Everyone needed to know a little about different things. There was also an imperative to have specialists to take that understanding to a higher level. The culture becomes more cohesive, because you need everyone.”

Then she adds, “I know one thing that a fisherman would not do. He would not take bananas on his canoe. Bananas are an offering to Kanaloa, who is the god of the deep ocean. He will come and take his offering. And the canoe will sink.”