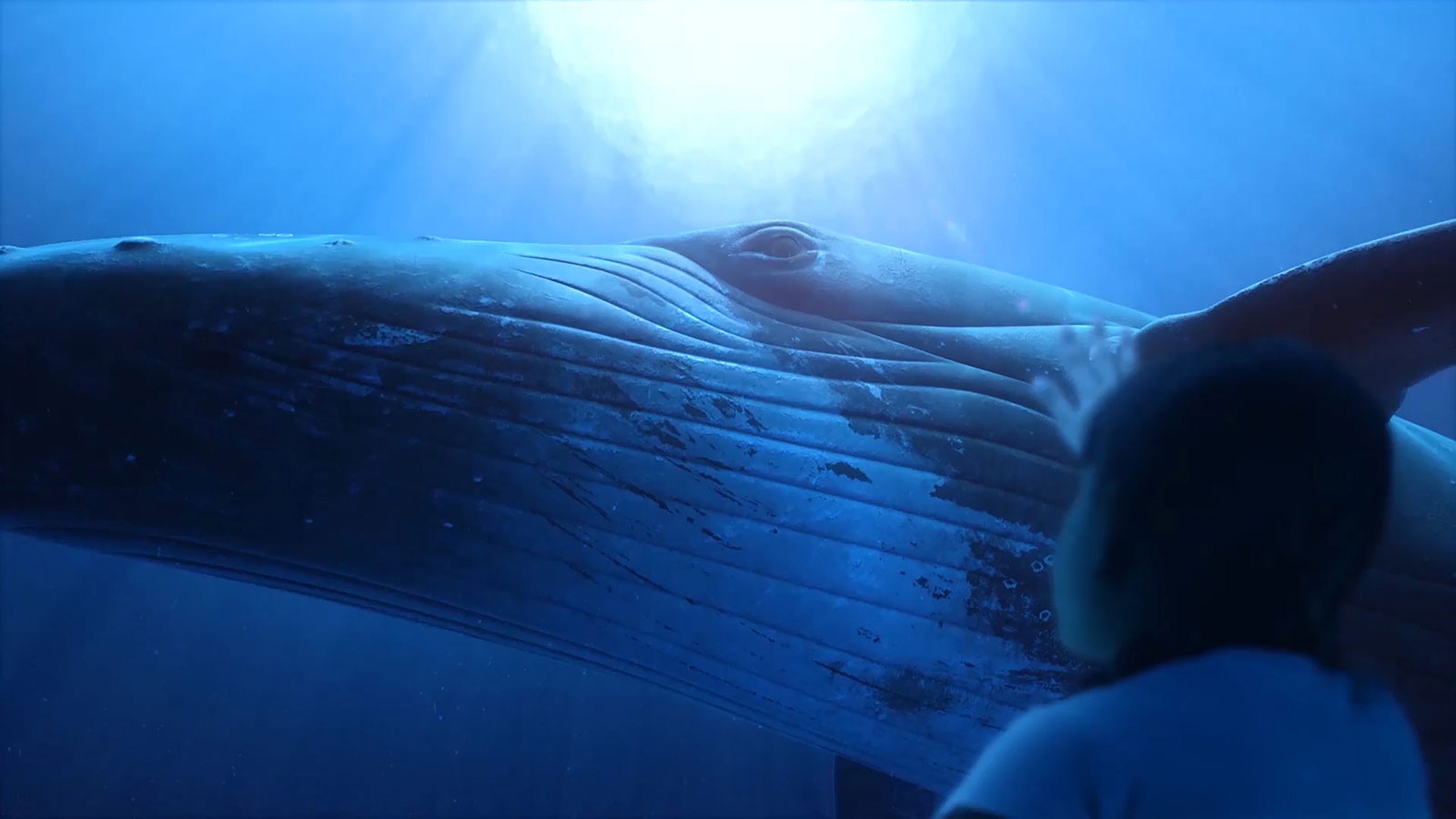

Every year, people come to Maui from all over the world to witness the arrival of the humpback whales, admiring their majesty with reverence, deference and awe. But there are more reasons than beauty to be concerned with whale conservation, especially as it relates to the health of the oceanic ecosystem, and one of the humpback’s most important contributions is, well, poop. Humpbacks consume approximately 3,000 pounds of krill and small fish per day while summering in the cold waters of Alaska. This tonnage is later returned to the sea in the form of organic waste that contains an abundance of nitrogen, iron and phosphorus. It then helps fertilize and grow phytoplankton, the very base of the oceanic food chain without which the sea as we know it would cease to exist.

But human beings were not always kind to these mammoths of the sea. Whaling was regular practice for thousands of years, and hunters traditionally used all parts of the whale — from the skin to the blubber to the bones — for food, tools and other commercial goods. A single whale could sustain an entire community for several months or more, but with technological advances such as gun-loaded harpoons and steamships, it was hardly a fair fight. People began hunting whales for sport rather than necessity, and by the 1970s, eight species of whales were listed as endangered, including our beloved humpbacks.

In 1975, Greenpeace launched the Save the Whales campaign, a grassroots movement that quickly captured the hearts of millions. They retaliated against the whaling industry by physically putting themselves and their boats between whaling ships and whales, and documented the cruel reality of commercial whaling on video. Their efforts led to an international ban on commercial whaling, thereby giving the whales a chance to rebound and flourish. Humpbacks went from a devastatingly low global population of only 10,000 to nearly 100,000 — and growing.

Today, however, the waters are muddled with new dangers. Marine debris and abandoned fishing nets (aka “ghost nets”) threaten entanglement, and overfishing of the humpbacks’ food sources has once again made them vulnerable.

“Whales are a sort of canary in the coal mine for climate change and anthropogenic [human-caused] impacts such as overfishing,” says Jessica Colla, director of education at the Maui Ocean Center. “You can’t just fix one threat, wipe your hands, and be done — it doesn’t work like that. Conservation has to take an interdisciplinary approach, and you have to be able to look at all threats at the same time.”

While a layperson might not be able to do much to curtail the abundance of fishing lines and garbage in our oceans, everyone can help by making small, thoughtful changes each day. For instance, respectfully observe humpbacks in the wild from at least 100 yards away — 300 when a calf is involved — and learn more about them on dry land at places like Maui Ocean Center’s Humpbacks of Hawaiʻi exhibit and Sphere. Practice sustainability as it relates to energy, waste and water, and teach your children to do so, as well. If everyone does their part, these small efforts will add up, and will give humpbacks a chance to survive and thrive.

“The story of the humpback whale is so inspiring,” says Colla. “Before the Save the Whales movement, the humpback population was dangerously close to extinction. Now, more than 10,000 whales return to Hawaiʻi to breed each year. Not only does it show the resilience of the species, but it also demonstrates how humankind can work together to protect these incredible animals from extinction.”

We Live Ocean Aloha. Go to https://mauioceancenter.com/ocean-aloha to learn more.