Story by Sara Smith, Jen Aly, Teya Penniman, Susanne Gnagy, Matthew Fullmer and Rita Goldman | Photography by Nina Lee

They protect endangered species, preserve the wilderness, and reverse the harm we humans do to land and sea. Heck, they’re even impervious to kryptonite.

What turns an ordinary human into a champion of the environment?

The folks we highlight in these pages can’t leap tall buildings or bend steel in their bare hands. Only one or two wear special costumes when defending Mother Earth.

But they do share a remarkable power: They can see how enormous a job it is to save a planet, and instead of becoming discouraged, grow enthusiastic at the myriad possibilities for making a difference. And through their conviction, in very different ways, they’re showing the rest of us that we can, too.

The Stewards

The Stewards

Last Thanksgiving, the Erdman family gave Maui something to truly be thankful for: permanently protecting more than 11,000 acres of ‘Ulupalakua Ranch from future development.

Pardee and Betsy Erdman purchased the ranch in 1963. In time, sons Christian and Sumner got involved; the latter now serves as ranch president. As if running a viable ranching operation in Hawai‘i weren’t challenging enough, the Erdmans practice a holistic approach to stewardship that includes proper pasture management, invasive-species eradication, extensive reforestation efforts, and revitalizing the watershed.

It’s a formidable task, encompassing 18,000 acres that stretch from shoreline to an elevation of 6,000 feet and span three different ecological zones. The Erdmans succeed, in part, through innovation.

“We’re always focusing on the next problem,” says Pardee. To stay ahead of ever-changing invasive weeds, the Erdmans use a system called managed multispecies grazing. Rotating cattle, sheep, horses, and goats—which have different palates and eating habits—can help keep down weeds such as Sacramento burr and fireweed. Plus, hungry livestock reduce fire potential by devouring overgrown vegetation. This protects the maturing native ecosystems, which reciprocate by improving the water and mineral cycles—a symbiotic relationship that is key to the Erdmans’ balanced land-management strategy.

The Erdmans also collaborate with ten different private, federal, state, and county conservation agencies and organizations. Their most enduring partnership is with Dr. Art Medeiros of the U.S. Geological Service, who heads the Auwahi reforestation project—the state’s most successful restoration of native dryland reforestation—all of it on ‘Ulupalakua Ranch land.

In 2003, the Erdmans joined another Medeiros project: the Leeward Haleakala Watershed Restoration Partnership, a collaboration of the region’s major landholders to restore more than 43,000 acres of native forests. The goal: to preserve habitat for many of Hawai‘i’s endangered plants and animals, and improve the health of the watershed. Native koa trees, for instance, are very important because their sickle-shaped leaves point down, ensuring that captured mist condenses into water that drips to the ground. The partnership’s efforts are working. “The water and mineral cycle has improved,” Sumner confirms.

Now, working with Maui Coastal Land Trust, the Erdmans have established an agricultural easement that will preserve 11,000 acres in perpetuity as a working ranch and native wildlife habitat. The easement includes one of Maui’s most iconic views—the glorious stretch of pastureland mauka (upslope) of Wailea—and all of Auwahi.

“This is the largest-ever voluntary-easement donation in Hawai‘i, a true gift for future generations of Maui,” says Dale Bonar, executive director of the Maui Coastal Land Trust. “The Erdmans have a strong love for the land . . . a decades-long commitment to conservation.”

If Sumner has his way, it won’t stop there. “It goes beyond just our family,” he says. “We hope to lead by example.”—Sara Smith

The Entrepreneur

The Entrepreneur

I turn down Wilma Nakamura’s grassy driveway in Keokea, and park beside her late ’90s Mercedes Benz. Wilma steps out of her front door, passing three lounging cats as she walks to greet me. Later I’ll learn that the car gets forty miles per gallon and runs on recycled vegetable oil.

As a graduate student at UC–Santa Barbara, where she received her M.F.A. in sculpture, Nakamura got an education in environmental activism. “Community gardens, composting, and recycling were commonplace,” she says. In 1991, she worked to have land donated for community gardens in San Ramon.

She grew up on the Big Island and was grateful to return to the Islands in 1992. “When you make Hawai‘i your home, you just signed up to look after the land and the ocean.”

An environmental entrepreneur, Nakamura has been involved in various Maui nonprofits. She serves as executive director of SharingAloha, an organization dedicated to preserving the environment through education and some unusual projects—such as collecting worn-out athletic shoes and shipping them to the mainland to have the rubber soles recycled.

SharingAloha also puts on the Art of Trash, an exhibit featuring art created from recycled objects. Nakamura signed on as coordinator in 1996, when Big Island artist Ira Ono brought the idea to Maui.

Cosponsored by Maui’s Community Work Day Program, Art of Trash creates opportunities for talking about reducing, reusing and recycling. The show is held annually—when funding is available—and will be at the Maui Mall this April in honor of Earth Day.

“We never know until the last minute what will show up,” says Nakamura. “It will blow you away, what people come up with.” Even the entertainment uses instruments made of trash. Last year, artist Robert Sargenti brought ukuleles made from cigar boxes and drums made from buckets. His musician friends “stole the show,” Nakamura says. “We invited them to play this year. They call themselves the Junk Band.”

Through another SharingAloha project, Nakamura teaches a class on composting and worm composting one Saturday a month—for which she charges a nominal $5. When people kept asking where to find a good, affordable composting bin, she researched to locate the best, and got the County of Maui to pay the freight, reducing the cost by more than half. The black cylindrical bins, which she sells at her classes in Kahului, are made from recycled plastic.

David McCreight, president of SharingAloha’s board, says Nakamura “makes activism seem effortless. She gets people interested and able to see that they can make recycling and composting a part of their life through simple changes.”

At the end of our interview, Wilma invites me to attend this year’s Art of Trash—and maybe even participate. The exhibit is open to all Maui residents.

She says people often attend the opening dressed in “trash,” and describes how she accessorized her simple black dress for last year’s show, sewing pleated ruffles of newspaper and attaching them to the bottom of the dress, then adding a cummerbund of black-and-white tissue to the waist.

Evidently, when your life is all about recycling, there’s no such thing as having nothing to wear.—Jen Aly

The Fisherman

The Fisherman

How does an orchid grower who speared uhu (parrotfish) to put himself through college become an advocate for bag limits, fishing licenses, and lay-net bans? For Darrell Tanaka, it’s a no-brainer. This Maui native has been fishing ever since he could hold a pole. By high school, he was spearfishing. He studied the commercial harvest of uhu for his degree in marine science. But over the years, he started to see big changes.

Back when he was a commercial diver, Tanaka could shoot most fish in only twenty feet of water. Now, he’d have to go a lot deeper. He notes that even ‘Ahihi-Kina‘u Natural Area Reserve, which he calls a “shining example” of a marine-protected area, has problems: a lot of the biomass in the reserve includes nonnative, invasive fish.

Now this avid fisherman has set his sights on species that don’t belong here—advocating for more regulations and building community involvement. And Maui’s reefs are reaping the benefits.

Tanaka helped get lay nets banned from Maui’s waters. He calls lay nets second in destructiveness only to dynamiting, but stresses that his focus is on Maui—not Maui County and not any other island. He explains, “Every island is unique. Maui’s reefs are small. It’s easy to overfish them.”

Tanaka’s latest endeavor is the Roi Round-Up, a spearfishing tournament focused on introduced species. Twice a year, divers compete to bring in the most roi, ta‘ape and to‘au, fish that compete with native species or simply devour them. (Printed on the Roi Round-Up souvenir T-shirt is the number of fish an adult roi consumes each year: 146.)

Maui’s Roi Round-Up is spawning similar tournaments on other islands. To keep the momentum going, Tanaka leads monthly “kill roi” days. “Divers,” he says, “are doing their part—one roi at a time, one reef at a time. They are stepping up to the plate.”

Tanaka is also quick to credit his Round-Up partners, Brian Nishikawa of Maui Sporting Goods, and Kuhea Paracuelles, Maui County’s environmental coordinator. They are equally swift with the praise. Paracuelles calls Tanaka the “horn,” bringing attention to marine issues and changing the attitude of divers, while Nishikawa commends Tanaka’s “pure motivation” to help the reef, with no personal gain involved.

Tanaka admits the family business—Sunshine Orchids of Maui—may suffer from his advocacy, but adds that his wife, Jackie, supports his passion. “It’s not what I want,” he maintains. “It’s what our reefs need. Everyone is entitled to their fair share, including the reefs.”

One Saturday afternoon at the Olowalu reef, Tanaka and nine other divers gather under the kiawe trees. They have been in the water for up to six hours, all of them targeting roi. The catch is small compared to earlier “kill roi” days, a sign their efforts may be paying off. Almost 1,000 roi have already been removed from this reef.

Tanaka didn’t know he’d find so much support. But as he observes, “If you never try, you never know.”

Keep trying, Darrell. Maui’s reefs need you.—Teya Penniman

The Forester

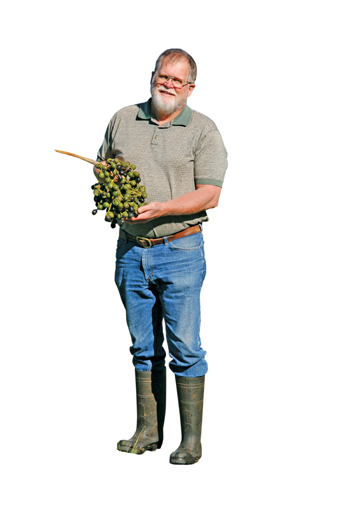

The Forester

Retired state forester Bob Hobdy has a passion for sharing his knowledge of Hawai‘i’s native ecosystems. Over the course of a forty-year career with the Department of Land & Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry & Wildlife, Hobdy became an authority on Hawaiian botany. He is credited with discovering twelve new indigenous species, and has extensively collected and documented indigenous plants for O‘ahu’s Bishop Museum. “Bob has a superior ability to see patterns, to see nature,” observes Dr. Art Medeiros, a research biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hobdy’s enthusiasm for local flora is rooted in his childhood on Lana‘i; when Bob was fifteen, famed Hawaiian botanist Otto Degener came to the island to collect samples in the forest, and Hobdy volunteered as his assistant. He went on to earn a degree in forestry at Oregon State University, but it was in the 1960s, as a young state forester on the island of Kaua‘i, that Hobdy truly began to learn about Hawaiian forests. “I would meet specialists and take them around the island [to show them where various plants were growing] and start learning below the surface about these different plants. It’s the best way to learn.”

Hobdy transferred to Maui in 1971 and focused on native and endangered species, invasive-weed and pest control, and watershed management. But his work has reached beyond the boundaries of his job. Hobdy has shared his expertise through his membership in such environmental organizations as the West Maui Mountain Watershed Partnership, the Maui County Arborist Advisory Committee, and perhaps most notably, the Maui Invasive Species Committee. With his exceptional eye, Hobdy has identified a number of alien species while they were still incipient on Maui and there was a chance for containment.

As an example, in the early 1990s, on a helicopter ride outside of Hana, Hobdy spotted an outcropping of Miconia calvescens, a highly invasive ornamental tree that has devastated Tahiti’s native forests. This was the first known incidence in the wild on Maui, but with its incredibly high rate of seed dispersal, miconia can quickly take over a native forest. Hobdy urged the Division of Forestry to establish an eradication program before the problem became widespread, and he went on to manage the first field crew of the miconia control program. According to Medeiros, “[Hobdy] blew the whistle on something that could have sealed the fate of Maui, had we waited just a few more years.”

Because of his willingness to collaborate with others, Bob Hobdy has been present for such conservation milestones as the formation of the East Maui Watershed Partnership and the Maui Invasive Species Committee—each the first of its kind in the state, and each subsequently duplicated on the other islands.

“I feel proud to be from Maui, because a lot of this stuff has been pioneered here,” Hobdy notes with quiet appreciation. “Maui people have this willingness to work outside of their boxes and cooperate. That’s the key to success.”—Susanne Gnagy

The Divers

The Divers

When a company’s official motto includes the word “bubbles,” you can pretty much assume the owners won’t be your average corporate types. Not, at least, if the owners are Don and Rachel Domingo, whose Maui Dreams Dive Company lives and breathes by the credo “Take only photos. Leave only bubbles.”

Maui Dreams opened in Kihei in 1999. Ever since, the Domingos and their ebullient staff have shared their love of diving with thousands of ocean enthusiasts . . . though not always in conventional ways. Each year, the company hosts Olympic competitions, Easter egg hunts, and pumpkin-carving contests—all of them under water. Rachel’s blog is filled with stories about close encounters with sea turtles, including the honu that mistook the diver’s hair for some succulent seaweed.

What the Domingos and their staff take seriously is protecting the ocean environment. Four times a year, the Maui Dreams crew participates in major marine cleanups with Project Aware, a nonprofit organization founded by members of the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI). The average haul per cleanup? Two-hundred pounds of fishing line, lead weights and hooks taken from Maui’s coastal waters. Nobody requires Maui Dreams employees to participate, says Rachel. They just do it.

In 2004, Don helped establish the Maui Reef Fund, an organization dedicated to the health of Maui’s marine ecosystem. Though Maui Dreams is small as dive companies go, with just one shop, one vessel and sixteen employees, its contributions to the Fund have been disproportionately generous: $23,000 in the past five years in monetary donations and in-kind services. Ananda Stone, project manager for the Fund, considers Don a rarity: “a visionary who gets things done.”

Case in point: the day-use mooring program that is Don’s brainchild. Moorings are crucial to the health of coral reefs where dive activities happen; they give vessels a place to tie up without having to drop anchor and potentially damage the reef. Don spearheaded a successful grant proposal to Project Aware to pay for the underwater drilling equipment required to install the moorings—though he’s also been known to pay out of pocket to get a mooring job done. He is also one of only a handful of divers approved by the state’s Department of Land & Natural Resources to repair and maintain day-use moorings.

In 2007, Don won the Living Reef Award for his contributions to marine education and environmental enforcement. He and the crew of Maui Dreams have also won the respect of colleagues like marine biologist Hannah Bernard of the Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund. “Don doesn’t [let the company] grow too big, too fast,” she says. “He grows with integrity. You can see it in [Maui Dreams’] energy and generosity.”

You can see it in the way the Domingos inspire their staff, as well. Teri Leonard, Maui Dreams’ shop manager, chairs the Reef Sustainability Committee for South Maui Sustainability, a grass-roots environmental organization; and co-chairs the Clean Water Committee for the Maui Nui Marine Resources Council—of which Don is also a member.

And then there was the Maui Dreams employee who, when asked what he wanted his business card to say, replied, “Defender of the Reef.”—Matthew Fullmer and Rita Goldman