Story by Jill Engledow | Photography by Nina Lee

Lahaina’s royal island is being resurrected, one square meter at a time.

Lahaina’s royal island is being resurrected, one square meter at a time.

One of the most significant archaeological sites in Hawai‘i, Moku‘ula was for years the kingdom’s capital, where historic documents like the Mahele (the great land division of the 1840s) and Hawai‘i’s constitution were drafted. University of Hawai‘i–Maui College Professor Janet Six compares it to world-heritage sites like Machu Picchu, and tells her students, “In the future, you’ll be telling your grandkids you worked at Moku‘ula.”

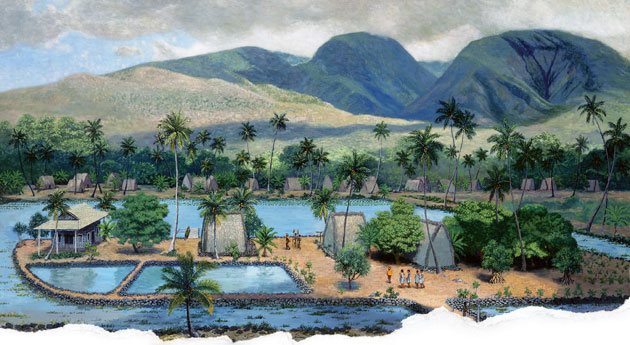

Moku‘ula was the focal point of a royal neighborhood in the area that now includes 505 Front Street, Kamehameha Iki Park, and the parking lot, tennis courts and abandoned softball field of Malu Ulu o Lele Park. Before nineteenth-century sugar planters diverted mountain waters to irrigate cane fields, many streams and freshwater springs kept the area cool and green.

Those springs created a large loko, or freshwater fishpond, called Loko o Mokuhinia. It was named for a daughter of one of Hawai‘i‘s greatest rulers, the fifteenth-century unifier of Maui, King Pi‘ilani, who lived near the pond’s edge. Kihawahine Mokuhinia was transformed upon her death into a mo‘o, or sacred lizard, a powerful guardian spirit who made the pond her primary home.

The worship of Kihawahine and the power she represented descended through the Pi‘ilani royal line to the divine chiefess Keopuolani. When conqueror Kamehameha I claimed this sacred princess as his wife in the 1790s, he also acquired Kihawahine. The area around Mokuhinia remained a headquarters for the royal family for decades. It was particularly important from 1837 to1845, when Lahaina served as the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i during the reign of Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), son of Kamehameha I and Keopuolani. With his sister Nahi‘ena‘ena, Kauikeaouli struggled to navigate the turbulent transition between ancient Hawaiian ways and those of newcomers who brought Western culture and religion.

In Hawaiian culture, the royal brother and sister were perfect mates, destined to produce children whose mana, or divine power, would be magnified by their parents’ merging. Missionaries who arrived in 1820 were horrified by this ancient custom and fought to keep them apart. But when Nahi‘ena‘ena died after bearing a short-lived child (possibly her brother’s), Kauikeaouli went into mourning. He turned the house his sister had been building on Moku‘ula into a shrine and sought refuge there from the change that surrounded him. In what visitors described as “a large chamber elegantly furnished,” he placed three coffins draped with scarlet velvet, containing the bodies of his mother, his sister and her child.

But Honolulu’s great harbor was becoming a center of commerce, and in 1845 the capital moved to that growing town. By the late 1800s, Mokuhinia was essentially abandoned. With stream water diverted for sugarcane, the lake became a stagnant, mosquito-breeding swamp. In 1914, Lahaina businessmen filled the swamp with harbor dredgings and dirt. Before the Friends of Moku‘ula began campaigning to restore the lost island and the pond that once surrounded it, almost no one remembered it existed.

The Friends grew out of Ka‘anapali Beach Hotel’s Project Po‘okela, a pioneer program begun in 1986 and taught by Hawaiian scholar Dr. George Kanahele. Po‘okela’s purpose was to teach the hotel’s employees about Hawaiian culture and history. Their studies led them to rediscover the sacred area that had been home to Maui chiefs for centuries, and to work toward its restoration.

The Friends envisioned a heritage/education center: the pond restored and the island uncovered, accessible only for ceremonial use but visible to everyone, a living reminder of the royal history of Lahaina. Led by founding Executive Director Akoni Akana, the Friends lobbied for funding of a 1993 archaeological excavation that unearthed, among other things, a wooden pier where it’s believed chiefs boarded canoes to cross the pond. A second archaeological study in 1999 recommended careful excavation to find the boundaries of the island, thought to encompass part of the ball field and an adjacent parking lot.

The Friends envisioned a heritage/education center: the pond restored and the island uncovered, accessible only for ceremonial use but visible to everyone, a living reminder of the royal history of Lahaina. Led by founding Executive Director Akoni Akana, the Friends lobbied for funding of a 1993 archaeological excavation that unearthed, among other things, a wooden pier where it’s believed chiefs boarded canoes to cross the pond. A second archaeological study in 1999 recommended careful excavation to find the boundaries of the island, thought to encompass part of the ball field and an adjacent parking lot.

That excavation is finally happening, “very, very slowly,” says Janet Six, who was in her first year at Maui Community College when the original excavation was done. Now teaching archaeology and anthropology at UH–Maui College, Six has connections at mainland universities with high-powered professors who are excited to be involved in a project of this importance.

Six has pulled together a winning partnership between the Friends’ Ka I‘imi ‘Ike (the pursuit of knowledge) educational program and the UH–Maui College Archaeological Field School. Archaeologists explore a fascinating site. Maui students gain hands-on experience in a profession with lots of job opportunities. (Six says there are twenty-one archaeology firms in Honolulu alone.) The community is invited to observe and even participate as history is uncovered. And the Friends of Moku‘ula see their dream move toward reality.

The chance for students to be mentored by professional archaeologists who have worked all over the world is a big deal for the college, says Six. Students in the field school earn six college credits by spending five weeks mapping, digging and sifting soil from one-meter-square holes. They gently scrape away dirt with a trowel, recording any objects they find, then sift the dirt they’ve removed to be sure they haven’t missed anything. The scraping stops when the texture of the dirt changes to the firmer soil of the island. “Once we get down to the island, we move sideways,” says Six. “The idea is to build on the work done in ’93 and ’99,” digging widely rather than deeply.

The project will continue during regular semesters one or two days a week, with more intensive work during the summers. The second five-week session started July 12, with Six’s former classmate, Dr. Karen Holmberg, as visiting archaeologist.

In the first session (May 14–June 18), workers found pieces of old glass and ceramics, a cow tooth, a handle made of bone, some buttons and “a lot of pop-ups from the ’70s,” says one of the students in that session, Joelle Yurkanin of Waikapu. There was also a red brick, possibly part of the brick palace built by Kamehameha I at Lahaina Harbor. Along with other artifacts, it is stored in the Friends’ office awaiting tests that will provide more information, says Friends Acting Executive Director Shirley Kaha‘i.

In the first session (May 14–June 18), workers found pieces of old glass and ceramics, a cow tooth, a handle made of bone, some buttons and “a lot of pop-ups from the ’70s,” says one of the students in that session, Joelle Yurkanin of Waikapu. There was also a red brick, possibly part of the brick palace built by Kamehameha I at Lahaina Harbor. Along with other artifacts, it is stored in the Friends’ office awaiting tests that will provide more information, says Friends Acting Executive Director Shirley Kaha‘i.

Yurkanin leaves this fall to study anthropology at UH–Hilo. She spent a significant portion of her summer on her hands and knees under blue tarps shading the work area, scraping away dirt. Students also used a tool called a theodolite to calculate the depth of each day’s excavation and to mark the sites of artifacts they found. “It was tedious, dirty and time-consuming and required a lot of patience,” she says of her Moku‘ula experience. “But it was wonderful. It’s so much fun, playing and working in the dirt and being a part of history. Janet always says the fieldwork is what makes or breaks you” in choosing this area of study, and Yurkanin says the session at Moku‘ula definitely reinforced her interest.

In addition to Maui College students and others who need the fieldwork credit to obtain their master’s degrees, Six’s connections will bring archaeologists and scholars from Brown, Harvard and Stanford Universities for a project she laughingly predicts will go on “forever.” After more than 400 years of ali‘i (royalty) living in this area, “we have to tease apart who lived where, when,” Six says.

While other ancient sites in Hawai‘i have been restored, this project is unusual because it has to be excavated, and because it exemplifies a new trend in the field. “This is what we call public archaeology,” Six says. “A lot of times this stuff is done in isolation. Public archaeology not only benefits scholars but also benefits the community.”

While other ancient sites in Hawai‘i have been restored, this project is unusual because it has to be excavated, and because it exemplifies a new trend in the field. “This is what we call public archaeology,” Six says. “A lot of times this stuff is done in isolation. Public archaeology not only benefits scholars but also benefits the community.”

The project was planned with community input and the advice of cultural experts. Each day on the site begins and ends with chants taught to the workers by the Friends’ cultural consultant, Hokulani Holt. And the public is welcome to ask questions, Six says; preserving the community’s heritage means both listening to the community and sharing what is being learned.

Anyone interested in joining in the work, whether learning the techniques of excavation or simply helping to keep the site cleaned up, can contact Kaha‘i at the Friends’ office. Potential volunteers have been plentiful, she says. “It’s everybody’s project, and that’s the cool thing.”

Visit online: www.mokuula.com. Phone: (808) 661-3659.