Story by Teya Penniman

Coral came first. In the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant, the coral polyp is the first life to emerge from the slimy darkness, solidifying its role in the formation and functioning of marine ecosystems. The Olowalu reef on Maui’s West Side has its own ancient coral—or, perhaps, had.

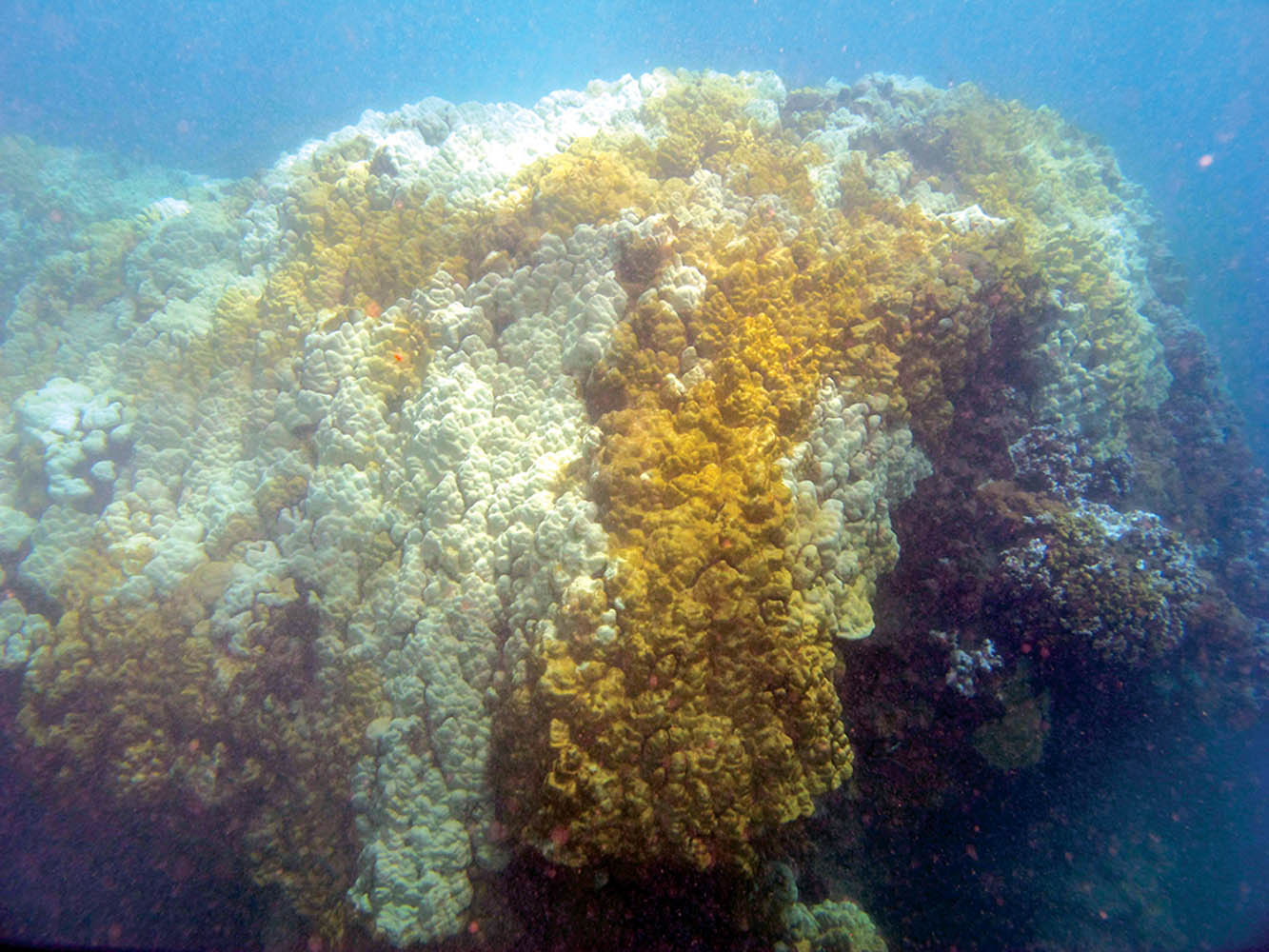

Olowalu’s reef covers nearly 900 acres—making it the largest intact fringing reef in the state. It’s also home to the largest and oldest free-standing coral colony. “Big Mama” spans twenty-seven feet and, based on core samples, was pushing 300 years. Large colonies generate new life and shelter many species of fishes and invertebrates. But the 2015 coral-bleaching event hit Big Mama hard, killing nearly 90 percent of its living tissue. The once-vibrant matriarch turned brown, smothered by turf algae.

“I know about climate grief,” says Darla White, longtime marine educator and the state’s co-manager of the Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary (jointly managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, and the Hawai‘i Department of Land & Natural Resources). White describes her first experience at Olowalu, in 1993: “Standing in knee-deep water, I stuck my face in and had a pufferfish staring back at me. There were fish all around me.” Yellow Porites lobe coral lined a wide, oatmeal-colored, sand channel; this golden corridor led to deeper waters and even more diversity.

It looks like a ghost town now, but White maintains her optimism. She highlights the need for good reef etiquette, and also community support for better management. “These animals [yes, coral polyps are animals] are resilient. It’s incredible what they can bounce back from, but [to do that] we have to remove the stressors.” She points to Olowalu’s designation as the state’s first “Hope Spot”—a global conservation campaign launched by renowned oceanographer and National Geographic explorer-in-residence Sylvia Earle. Shining a spotlight on treasures like Olowalu can bring more awareness and, perhaps, protection. Governor David Ige’s 2016 Sustainable Hawai‘i Initiative recognizes the need for more aggressive action, with a goal of effective management of 30 percent our nearshore ocean waters by year 2030.

Big Mama might be gone, but she’s still talking to us. Will we listen?

What You Can Do:

Practice reef etiquette.

- Don’t stand or walk on coral. (The weigh crushes living organisms.)

- Use reef-safe sunscreen. (Read the label-oxybenzone harms coral larvae.)

- Don’t feed the fish. (Hand-fed fish become habituated to human feeding, are more vulnerable to predation, and don’t get their need nutrients.)

Learn More & Get Involved:

Many organizations on Maui are eager to share their knowledge about our coral reefs. Here are three:

- Maui Nui Marine Resource Council (MauiReefs.org)

- Maui Ocean Center (MauiOceanCenter.com)

- West Maui Ridge to Reef Iniative (WestMauiR2R.com)