Story by Jill Engledow | Photographs courtesy of Friends of Old Maui High School & Ron Dahlquist

When Maui High School was founded in 1913, the island was a rural community of some 32,000, mostly immigrants working in cane fields and sugar mills. Education was available only though grammar school, though boys could continue into their teen years at Lahainaluna, then a vocational-trade school. The upper classes hired tutors, or sent their children to Punahou on O‘ahu or to the Mainland for secondary education. But a growing Caucasian middle class wanted their children educated at home.

When Maui High School was founded in 1913, the island was a rural community of some 32,000, mostly immigrants working in cane fields and sugar mills. Education was available only though grammar school, though boys could continue into their teen years at Lahainaluna, then a vocational-trade school. The upper classes hired tutors, or sent their children to Punahou on O‘ahu or to the Mainland for secondary education. But a growing Caucasian middle class wanted their children educated at home.

So Maui High was begun, the island’s first coeducational public high school and the third in Hawai‘i. Sited at an incredibly beautiful location two miles above Ho‘okipa Beach, the school overlooked the ocean and a coastline stretching to the cloud-crowned mountains of West Maui. Haleakala provided a backdrop for a verdant campus surrounded by fields of sugarcane, cooled by trade winds and kept green by windward showers. Generations of students would enjoy this quiet, spacious campus.

The school was located near the plantation camp of Hamakuapoko, then a thriving village not far from the population centers of Pa‘ia and Pu‘unene. At the end of the first year, the school had sixteen freshmen and sophomores, most from Maui’s prosperous Caucasian families.

That was soon to change, as immigrant families seeking a better future for their children took advantage of this opportunity for a free education. Some middle managers in the plantation community opposed the education of these “alien” children (most of whom were, in fact, American citizens by birth). If you gave such children an education, they would grow up wanting more than a job in the fields. And in a time when race and ethnicity were seen as legitimate dividing lines in society, some white parents preferred that their children not be exposed to other cultures and to those who communicated in pidgin English.

That was soon to change, as immigrant families seeking a better future for their children took advantage of this opportunity for a free education. Some middle managers in the plantation community opposed the education of these “alien” children (most of whom were, in fact, American citizens by birth). If you gave such children an education, they would grow up wanting more than a job in the fields. And in a time when race and ethnicity were seen as legitimate dividing lines in society, some white parents preferred that their children not be exposed to other cultures and to those who communicated in pidgin English.

Yet deep within the souls of many Island leaders were values they had received from their missionary ancestors, whose earliest efforts in Hawai‘i had included creating schools for the native population. And Hawai‘i was a U.S. territory, perhaps someday to become a state. If this were to be an American community, a free education should be open to all.

From the beginning, it was a case of “build it and they will come.” The Kahului Railroad added a train route especially for Maui High students that started in Wailuku and picked up passengers from towns and plantation camps along the way. The train dropped off Central Maui students at Hamakuapoko and then continued east to collect those in the villages at Ha‘iku, Pauwela and Kuiaha. Others arrived by buggy or on horseback or walked barefoot from the closest plantation camps.

Soon the first seven-room wooden structure was crowded with students. In the beginning, probably none of them, whether the children of fieldworkers or of plantation owners, had much of an idea what high school was supposed to be like. Yet within a few years, a typical American high school had sprung into existence in the midst of the cane fields, complete with student government, athletic teams, pep rallies, a yearbook and a school song.

The credit for this must go to the teachers and their principals, well-trained, progressive educators recruited from the Mainland, who initially taught a curriculum that included Latin, French, English, history, business and domestic science. These educators continued to set high academic standards as the curriculum expanded, exposing youngsters to Shakespeare and algebra, teaching them to write poems and to type a perfect business letter. They helped children who had entered school speaking only pidgin or Japanese to communicate in perfect English. And, cognizant of the community’s primary industry, they trained young farmers in a first-rate agricultural program

At the same time, the faculty emphasized values of democracy and equality as they guided their young charges in creating a society in miniature, with representative government, a student police force and court, service clubs and cultural activities. Though the student body included its share of kolohe (mischievous) boys who found out-of-the-way corners to smoke and throw dice, Maui High was a remarkably civilized and peaceful place to learn.

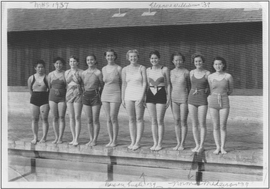

At the center of school life was the administration building designed by architect Charles W. Dickey, a Maui boy who would become famous for creating a distinctive Hawaiian style of architecture. He drew up plans for a single-story, reinforced-concrete school with a U-shaped layout, built in the Spanish Mission Revival style. The building opened with great ceremony in December 1921, and became the school’s emblem, its broad front steps the favored place for yearbook pictures.

Lorraine Sato Tamaribuchi recalls what that building meant to students coming from dusty camps where families squeezed into tiny cottages that often had no indoor plumbing. “It was such a gift to kids like us,” Tamaribuchi recalls. Each day the wide, shallow steps of this quietly elegant building welcomed the students, its side wings stretched out like open arms, raising their expectations about what life might offer.

Many Maui High graduates grew to prominence, on Maui and beyond. They included noted ethnobotanist Beatrice Krauss; Bank of Hawai‘i President Wilson Cannon; James Y. Ohta, first Asian-American executive in the Boy Scouts of America; Earl Isao Tanaka, The Maui News managing editor, and his photographer brother Wayne. There were judges: Hawai‘i Supreme Court Justice Soichi Ogata, Harriette Holt, Kase Higa and George Fukuoka; and politicians: U.S. Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink, Maui Mayors Elmer Cravalho, Hannibal Tavares and Alan Arakawa, Maui County Councilwoman Velma McWayne Santos, state Senator Mamoru Yamasaki.

Many Maui High graduates grew to prominence, on Maui and beyond. They included noted ethnobotanist Beatrice Krauss; Bank of Hawai‘i President Wilson Cannon; James Y. Ohta, first Asian-American executive in the Boy Scouts of America; Earl Isao Tanaka, The Maui News managing editor, and his photographer brother Wayne. There were judges: Hawai‘i Supreme Court Justice Soichi Ogata, Harriette Holt, Kase Higa and George Fukuoka; and politicians: U.S. Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink, Maui Mayors Elmer Cravalho, Hannibal Tavares and Alan Arakawa, Maui County Councilwoman Velma McWayne Santos, state Senator Mamoru Yamasaki.

But while those graduates helped shape Maui’s history, the island itself was changing. The closing of plantation camps had shifted the population to Central Maui. In 1972, Maui High’s faculty and staff, its students and programs, relocated to Kahului. Left to weeds and vandals, the old campus deteriorated. Teachers’ cottages, athletic buildings and fields were lost to fire or bulldozers. The agriculture program’s orchard, with dozens of fruit-tree varieties, died of old age and neglect. The auditorium known as “the Barn,” where young thespians had performed, where prom dancers swayed cheek-to-cheek and graduates had marched, burned down in 2001.

Most disturbing of all was the loss of the beautiful old administration building. Its library was taken over by a banyan tree. Weeds sprang up on the front lawn, the roof collapsed and graffiti defaced the walls.

But the spirit of old Maui High still lives. Last September, more than 1,200 graduates returned for a grand reunion organized by the Friends of Old Maui High and co-chaired by alumni Rodney Inciong and Richard Higashi. Participants traveled from as far as Germany and Japan, some to greet friends they had not seen since high school. For three days, that throng filled the country campus and walked its open-roofed halls, hugging classmates and remembering days of friendship and learning. Cheerleaders led by Sylvia Harima, class of 1945, shook blue-and-white pom-poms, and a couple of graduates from the 1960s demonstrated that they could still do the splits. Alumni sang the alma mater (composed by a French teacher in 1919) with a band made up of young musicians from the new Maui High in Kahului and old-timers whose initial reaction to the idea had been, “You gotta be joking! I nevah touch my instrument for ovah forty years!” At least one graduate was moved to tears. “I never thought I’d hear that song played at this school again,” said Barbara Tanner, class of ’56.

People really care about this school—not only those whose school spirit lingers long after they received their diplomas, but also newcomers who are entranced by its architecture and history. Barbara Long, president of the Friends of Old Maui High School, is one of these. She was among a couple of dozen Mauians who responded to a call in 2003 from Community Work Day Director Jan Dapitan to begin the enormous effort of revitalizing the twenty-three-acre campus.

People really care about this school—not only those whose school spirit lingers long after they received their diplomas, but also newcomers who are entranced by its architecture and history. Barbara Long, president of the Friends of Old Maui High School, is one of these. She was among a couple of dozen Mauians who responded to a call in 2003 from Community Work Day Director Jan Dapitan to begin the enormous effort of revitalizing the twenty-three-acre campus.

In 2006, as the Friends prepared to welcome reunion attendees to the newly spruced-up campus, Barbara Long asked me to help write a book that would tell the story of old Maui High. The months I spent reading yearbooks and listening to alumni made it clear why the school’s many graduates treasure the memories of their years there, and why Maui—and in fact the whole nation—owes a debt of gratitude to this country school.

Of all the distinguished students of Maui High School, Patsy Takemoto Mink is the best known. Student body president in 1943–1944 and class valedictorian, this Hamakuapoko girl excelled throughout high school, finding a haven there from the war years’ prejudice against Japanese Americans and the customary second-class status accorded to females.

Things were different in the outside world. Mink applied to many medical schools only to be turned down, switched to law and found, after earning her degree, that no Honolulu law firm would hire a woman. So Mink began her own practice. She joined in the Democratic revolution of the 1950s that eventually made her the first Japanese-American woman elected to the Territorial House of Representatives and the first nonwhite woman elected to the U.S. Congress. There she became principal author of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, now known as the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, landmark federal legislation that ensured equal educational opportunities for girls and women. One result was to require the ratio of spending on athletic and educational programs to be proportionate to enrollment. Title IX would revolutionize women’s sports.

Mink’s high ideals and support for women, poor people and others who might not have a voice led the Friends of Old Maui High School to choose her name for the new incarnation of the school where she had learned so much. An Environmental Protection Agency grant and lots of volunteer work launched efforts to create the Patsy T. Mink Center, opening the campus once more to productive use. The Friends hired planners Chris Hart & Partners to help come up with ideas to advance the legacy of old Maui High School and the ideals of Patsy Mink.

Not long after the reunion, the campus was quiet again on a Saturday morning when members of the Friends gathered in the cafeteria to hear what the planners had put together. That ambitious plan envisions a place where children and adults can come for retreats and education, a model of environmental sustainability and “green” architecture that takes full advantage of the natural setting and remaining buildings of the campus. Many steps remain before the old school where a thousand teenagers once learned and played can flourish again. But it’s a journey that will be powered by the spirit still strong in the many hearts that love the graceful arches of old Maui High School.

TIMELINE

September 1913: Maui High and Grammar School opens at Hamakuapoko with sixty-one students, sixteen of them in two high school classes.

June 1916: First five students graduate.

June 1919: French teacher Cecyl Holliday composes Maui High’s alma mater.

December 1921: Administration building designed by noted Hawai‘i architect C. W. Dickey is built with $66,000 appropriation from the Territorial Legislature.

1922: Maui High’s varsity football team sails to Hilo to play first off-island game.

1926: Grammar school classes move to Spreckelsville as Maui Standard School, later known as Kaunoa School.

1931: An occupational survey of the 447 students who graduated from 1918 to 1930 shows “there are no chronic loafers among the graduates,” The Maui News reports.

1932: First Asian staff member, 1925 Maui High graduate Hisao Nakamura, puts his prize-winning typing skills to work as school secretary.