Story by Teya Penniman

In the waist-high waters of Koieie Fishpond in north Kihei, a small group of men and women shuffle across the sandy bottom, locating rocks with their feet, diving below to raise the stones, then heaving them onto the growing pile at one end of a gap in the rock wall. The stones, chunks of lava that Hawaiians hauled and wedged into place some 400 to 500 years ago, lie strewn across the pond’s bed like a broken string of pearls, scattered by storms and several centuries of neglect.

In the waist-high waters of Koieie Fishpond in north Kihei, a small group of men and women shuffle across the sandy bottom, locating rocks with their feet, diving below to raise the stones, then heaving them onto the growing pile at one end of a gap in the rock wall. The stones, chunks of lava that Hawaiians hauled and wedged into place some 400 to 500 years ago, lie strewn across the pond’s bed like a broken string of pearls, scattered by storms and several centuries of neglect.

Aoao O Na Loko Ia O Maui (Fishpond Association of Maui) has been working since 2005 to restore the ancient pond, and in the process, connecting volunteers to Hawaii’s past. Executive Director Joylynn Paman explains, “We use the same rocks that were used to build the original wall.”

Today, December 17, the work also honors Kimokeo Kapahulehua, cultural practitioner, founder and president of Aoao O Na Loko Ia. On this, his sixty-fourth birthday, he’s issued a challenge: help him rebuild sixty-four feet of the pond. “We’re enriching the shoreline,” he says. “With the wall, the fish, opihi, crabs, lobsters, sea urchins . . . all these will come.” It’s a goal that has brought Kapahulehua to Koieie week after week, year after year. “When the wall is built,” he says, “it becomes a house for the people of the sea.”

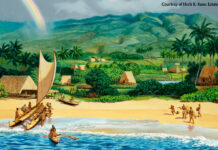

Hawaii’s first settlers found the islands’ sheltered coves and lagoons ideal for fishpond development; their early stonework joined land and sea, delivering the Pacific’s bounty to fishermen with a dip of net or thrust of hand. Teeming aholehole (silver perch) sparkled in shallow waters; pua ama (mullet fingerlings) grazed on floating algae, while their larger kin, amaama, fed along the bottom.

The structural diversity and sheer numbers of na loko ia (fishponds) made the Hawaiians unique among other fish-rearing peoples of the Pacific. Along the fringing reefs, stone-flanked lanes drew fish in or out of the larger walled area; as the fish swam against the tidal current, nets placed across the openings secured the day’s meal. Enclosed ponds, like Koieie, had makaha, or sluice gates, built into massive seawalls. Lashed together, the upright sticks were far enough apart to allow small fry into the pond, but too close for larger fish to pass back out once they grew fat.

Not all fishponds were along the coast. Fish-stocked taro patches, inland pools fed by freshwater streams or springs, and brackish, dune-sheltered ponds rounded out the mauka-to-makai (mountain-to-sea) system of aquaculture that once flourished in Hawaii. Many ponds were royal in origin, with alii (chiefs) claiming rights to the fish. Construction of a walled pond might require thousands of workers, who passed large rocks hand to hand, sometimes from sources a mile or more from the site.

Not all fishponds were along the coast. Fish-stocked taro patches, inland pools fed by freshwater streams or springs, and brackish, dune-sheltered ponds rounded out the mauka-to-makai (mountain-to-sea) system of aquaculture that once flourished in Hawaii. Many ponds were royal in origin, with alii (chiefs) claiming rights to the fish. Construction of a walled pond might require thousands of workers, who passed large rocks hand to hand, sometimes from sources a mile or more from the site.

According to legend, many loko ia were built by Menehune. Some say they were a fabled race that could complete the arduous task in a single night. By other accounts, Menehune were peaceful, flesh-and-blood descendants of early Marquesan settlers. Later waves of Polynesian voyagers came from Tahiti, whose warrior chiefs commanded that the mana hune (“small power” people, in Tahitian) build fishponds or temples over a few days or perish. The original settlers would come down from the mountain caves where they were hiding and labored through the night to complete the task and avoid slaughter. Whether by human hand or mythical being, each fishpond was a phenomenal feat of construction.

Why did a people surrounded by ocean undergo such Herculean efforts? Paman says that ancient Hawaiians knew what Western research took centuries more to verify: the energy efficiency of fishponds is staggering. Most fish grown in island ponds were herbivores—varieties like mullet and milkfish that eat the limu (algae) and microscopic plants that thrive in shallow, sunlit water. A fishpond that produces five tons of limu and phytoplankton can yield half a ton of herbivorous fish for consumption. The same amount of limu and plankton produces only ten pounds of large, carnivorous fish in the open ocean. Cultivating herbivorous fish provides 100 times more protein than open-ocean fishing. Hawaiians were eating low on the food chain 1,000 years ago, and sustaining about the same number of people who call Hawaii home today.

Each loko ia typically had its own guardian, or kiai, a person charged with protecting the pond’s liquid assets from two-legged thieves and finned predators like barracuda. The kiai kept the pond in good repair and stocked and fed the fish. Fishponds also had a different kind of guardian: the moo akua. These large, lizardlike gods helped fill the watery pantry, but the presence of moo could also turn both water and fish bitter.

Loko ia figure in numerous ancient legends, such as this one taken from Hawaiian Fishing Legends, edited by Dennis Kawaharada, and several other sources:

An accomplished fisherman named Kuula lived in East Maui with his wife, Hina, and built a fishpond between Hana Bay and Hamoa, at Lehoula. Wise and generous, Kuula revered the gods, and provided abundant fish from the pond for his alii (chief). A great puhi (eel) lived in a cave on Molokai, and was worshipped by the people there. When the eel began to steal the fish from Kuula’s pond, Aiai, son of Kuula and Hina, devised a plan. Using a heavy stone for weight, Aiai dove into a cave off East Maui and found the eel’s hiding place. With his father’s sacred fishhook, he snagged the eel, and with ropes tied to two canoes, his neighbors helped haul the eel into shallow water, where Aiai killed it. The eel’s caretaker on Molokai learned of its death and sought revenge by turning the alii against Kuula. Kuula’s house was burned, and he and Hina became spirits of the sea. Aiai escaped, taking with him his father’s fishing knowledge and power. He destroyed the alii who had killed his family, and taught the people how to fish and give proper thanks to Kuula, including the building of koa [fishing shrine], where the first fish caught was left as an offering.

The presence of loko ia was synonymous with wealth. As renowned historian Samuel Kamakau observed, “A land with many fishponds was called fat.” A 1990 archaeological survey documented 488 historic loko ia across the Hawaiian Islands, with 44 on Maui, 4 on Lanai, and an impressive 74 on Molokai. Longtime Hawaiian activist Walter Ritte, who is working to restore Keawanui Fishpond on Molokai, says his island was known as aina momona, or “fat land,” for its ability to feed thousands from its productive ponds.What happened to the loko ia?

Even during the heyday of aquaculture in the Islands, the ponds were vulnerable to intentional destruction by warring armies. Tsunamis and storms also took their toll. But most damage occurred after Captain Cook’s arrival. Western diseases decimated the Hawaiian population, in many places leaving no one to care for the ponds. As the introduction of cattle and the sandalwood trade denuded forested slopes, fishponds began to fill with silt from eroded hillsides. Some ponds, like Mokuhinia at the royal residence of Mokuula in Lahaina, were intentionally filled. Walls that once stood proudly against the relentless sea began to disintegrate.

By 1973, only fifty-six fishponds in the Hawaiian Islands were considered worthy of historic preservation. In 1994, six fishponds were in active production. As the fishponds disappeared, lost also were stories of place. Kepa Maly, executive director of the Lanai Culture & Heritage Center, says no knowledge survives of who made the Lanai fishponds nor of the kapu (prohibitions) associated with them.

Now, it seems, the guardians have returned. Work at Keawanui embodies the same kind of cooperative, inventive problem-solving and persistence of old. Ritte’s organization, the Hawaiian Learning Center, has marshaled thousands of hours of volunteer labor to restore the pond. Days before one section was to be completed after years of effort, the 2011 tsunami took a whole wall system down. Ritte says, “We drank beer, cried for a day, and went back to work.”

Today Ritte is experimenting with different species of fish, shrimp, and mollusks, pushing ancient technology in new directions as he moves in traditional concert with moon, sun and tide. “You can’t know where you’re going unless you know where you came from,” he says. Ritte sees fishpond restoration as central to weaning Hawaii from an unsustainable reliance on imported food.

For today’s kiai, the loko ia hold more than a promise of satisfying an appetite for fish. Ritte’s project engages local students to help restore the pond. After hundreds of years of disuse, much knowledge has been lost, but he says, “The only way to get it back is by doing it.” Like Ritte, Paman says work at Koieie is as much about education as about providing a source of food. “It’s not just about ‘Hurry up, get the wall built.’ We’re learning what works.” Restoration is a slow process. “A fishpond,” she says, “is never complete.”Back at Koieie, a line of high school students stretches from the shore to the wall, passing buckets of coral rubble scooped from the beach to pour on top of a section that is almost done. “The small stones,” Paman says, “are just as important as the big rocks,” acting like cement, filling in the cracks and crevices. With each bucket of pebbles, the young volunteers are securing more than a wall—they are bridging Hawaii’s past with its future.

To learn more about Hawaiian fishponds—and how you can help restore them—visit www.mauifishpond.com.

Easy Viewing

North Kihei: Koieie Fishpond is just off Kalepolepo Park, south of the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary.

East Maui: Private Haneoo and Kuamaka fishponds are visible along the road south of Koki Beach, past Hana on the way to Kīpahulu.

Molokai: Many fishpond outlines are visible along the south shore of the island, especially evident from the air.