Rita Goldman | Illustrations by Guy Junker

I must have read The Swiss Family Robinson three or four times as a kid. I loved the tale of that family, shipwrecked on a tropical island, who manage with perseverance and ingenuity to build an idyllic life. Back then, I would have given anything to live in a many-roomed tree house like theirs, woven as it was into the very fabric of nature.

I must have read The Swiss Family Robinson three or four times as a kid. I loved the tale of that family, shipwrecked on a tropical island, who manage with perseverance and ingenuity to build an idyllic life. Back then, I would have given anything to live in a many-roomed tree house like theirs, woven as it was into the very fabric of nature.

Not that the Robinsons and their tree house are on my mental radar as I cross the Manoa campus of the University of Hawai‘i. I’ve come to see the work Dr. Stephen Meder, his colleagues and students in the School of Architecture are doing to make all our buildings more in tune with nature. Meder is not only a professor of architecture; he serves as director of the Center for Smart Building and Community Design, part of the Sea Grant Program funded largely by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (When I ask him why on earth NOAA funds architecture studies, he says, simply, that what happens on land, for good or ill, affects what happens in the ocean.) “At Sea Grant, we look into everything: planning issues, transportation, the impact of development, building design and institutional retrofits. The goal is to have the interaction among the built, natural and human environments be more mutually beneficial.

I first met Professor Meder on Maui, where he helped Montessori School plan its LEED-certified campus expansion. (A buzzword these days, LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design—a rating system created by the U.S. Green Building Council to encourage sustainable practices in design, construction, and building maintenance.) Knowing his passion for environmentally responsible living spaces—and having absorbed the doomsday warnings of documentaries like An Inconvenient Truth—I half-expect a lecture on the need for us Americans to lower our standard of living, sacrifice our creature comforts, and adopt draconian practices to save the planet and ourselves.

To my surprise, Meder not only exudes a Star Trekkian faith that technology can solve our problems, he flat-out doesn’t believe that you can help the environment by making people less comfortable—at least not so long as they have a choice.

Of course, that may not be much longer. Like the shipwrecked Robinsons, we who live in the Islands are separated from the rest of the world by a vast ocean. As cheap and abundant oil becomes a thing of the past, our ability to live well here will depend on how well we steward the resources at hand.

“We burn more oil for electricity than any other state in the country,” says Meder, “and we have the highest energy costs. Yet we also have more opportunities for renewable energy than anywhere else in the world: deep-seawater energy conversion, waves, wind, solar.”

Lowering the amount of energy your home uses not only saves you money, it may actually do more good for the planet than buying a fuel-efficient car. According to the American Institute of Architects, transportation accounts for 27 percent of the world’s use of carbon-based fuels. Buildings consume a whopping 48 percent—about 8 percent in construction and materials, the rest in maintenance and operations: air-conditioning, heating, appliances.

In Hawai‘i, says Meder, “the irony is that we’re designing inefficient buildings that use too much energy to make people comfortable—in the most perfect climate in the world.”

His words call to mind some of the subdivisions I’ve seen spring up in Maui’s Central Valley and on the island’s sun-drenched south shore: rows of one- and two-story boxes with small windows, low-pitched roofs with little overhang, tiny yards whose saplings won’t provide significant shade for a decade or two. But given the high cost of land and construction, what else can we do?

A lot, says Meder, as we stroll over to the school’s Energy Lab. “Building a more efficient home doesn’t have to cost more, and they’re cheaper to operate.”

Energy Economy

My second surprise comes when we arrive at the lab, where cutting-edge technologies are being integrated into architectural design. (Besides educating tomorrow’s architects, the school collaborates with such entities as the U.S. Department of Energy; the state’s Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism; the American Institute of Architects; and the Building Association to put environmental design principles into practice.) Whatever bells and whistles I was expecting, the Energy Lab doesn’t have them. It’s located in an old storage bay. Aside from a dozen or so computers scattered around the room, the only high-tech apparatus I see is a metal podium with large dials along the post that tilt the platform to various angles. (A heliodon, I later learn, the device helps architects determine how sunlight will strike a particular building design at various latitudes and longitudes over the course of a year). Along the walls, and spread out on tables, are samples of building materials so low-tech in appearance, I wonder whether all the lab’s cool gadgets are out on tour.

And that’s the point—or at least one of them—that Meder and his colleagues hope to make. “The beauty is that it doesn’t take high-tech materials to make your home more energy efficient. Most of the technology we need, we already have.”

To illustrate, he picks up what looks like a small block of particleboard with a strip of aluminum affixed to one side. It’s an example of a radiant barrier, one of the best investments a homeowner can make in reducing home energy costs—especially here in Hawai‘i, where air-conditioning is second only to the conventional water heater as a major energy hog.

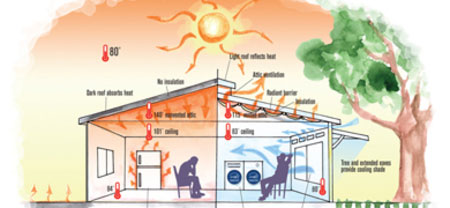

“The rule of thumb,” says Meder, “especially here in the tropics, is to reduce the amount of heat that gets through the building envelope—the roof, walls, doors and windows. At our latitude, the sun beats down most on horizontal orientations.”

If yours is a typical home, the main horizontal orientation is your roof; whatever you do to help it reflect the sun’s rays means less heat absorbed into the home. A radiant barrier stops the radiant heat transfer by reflecting the energy back the way it came. But while metal’s shiny surface is reflective, it’s also a good heat conductor—as anyone who’s ever picked up a hot pan without oven mitts can attest. Leaving about an inch of air between the roof and the radiant barrier breaks that conductivity.

“A radiant barrier costs about seventy cents a square foot,” Meder says. “When installed properly, it can reduce radiant heat gain by about 80 percent.”

And here’s something I hadn’t thought about since high-school physics: because light surfaces are reflective, and dark surfaces absorptive, changing the color of your home’s exterior can change the temperature inside. “Light-colored shingles reduce radiant heat gain by 25 percent,” says Meder. But light-colored shingles also show mold, so many people won’t use them. One compromise is medium-toned shake; the air spaces around the slabs of shake help reduce the conductive transfer of heat. (Want to really go green? Install sod on your roof, atop an impermeable plastic barrier. That vegetative cushion will happily soak up the sun’s warmth before it enters your home, and create more oxygen for the atmosphere, while it’s at it.)

And while those of us who transplanted here from colder climes are more familiar with insulation as a means of retaining indoor heat, it works just as well to keep heat out and cool air in. “If you don’t have a temperature difference inside and out, insulation isn’t that critical,” says Meder. “But if you’re air-conditioning the home, insulating the roof and walls that are exposed to solar heat gain is vital.” Forego it, and you’re paying to cool not just your house, but also its immediate vicinity.

Adding insulation and radiant barriers, installing a solar water-heating system, replacing inefficient appliances with those that earn the Energy Star rating . . . such measures are relatively inexpensive, especially when you figure in tax rebates and lower energy bills that can recoup your investment in just a few years. And they’re easy to install, if you’re refitting an existing home. If you’re buying, building or renovating, you’ve got even more options, such as extending roof overhangs and recessing windows to provide greater shade, and “low-E” (low-emission) windows whose virtually undetectable metallic glaze reflects around a third of the heat of the sun’s rays, while transmitting most of the visible light.

How you orient your home on the property can make a major difference, too.

At Home In The Islands

Upstairs, we meet Clark Llewellyn, AIA. The new dean of the UH School of Architecture, he’s an avuncular fellow with an engaging smile above a white fringe of beard. Llewellyn picks up the subject of building orientation: Which direction does your breeze come from, and how much breeze do you want indoors? Putting your operable windows on the windward side increases the airflow; size, position, and type of window affect how much airflow you receive, and where.

Orienting a dwelling properly also takes into account that east- and west-facing walls get the most sun; in warmer climates, it makes sense to extend the rooflines on those sides.

Don’t lower eaves reduce the amount of interior daylight?

“There are all kinds of ways to deal with that,” he says. “Add a light shelf, which reflects light deeper into the house. Use skylights to illuminate an interior room. If you can eliminate a lot of the lighting, you’ve got a major portion of energy saved. Compact fluorescent lights (CFLs) use less energy and create only a fraction of the heat of incandescent bulbs, but CFLs have mercury, and people are concerned about their cumulative effect in landfills. Nothing’s perfect, but daylight’s close.

“Housing in Hawai‘i can be so minimal compared with other places,” he adds. “I’d get rid of the air-conditioning, add screens to the lanai, and live outdoors more. The Pacific Club, here in Honolulu, is a series of individual small rooms with covered walkways. If privacy and security are concerns, I think courtyard buildings would be worth exploring.”

I almost don’t hear him; my mind is still stuck on the image of CFLs leaching mercury into the landfill. Llewellyn nods. Even going green requires choices.

“When I deal with clients as an architect, they tend to have an oversimplified view: three bedrooms, two baths, this many square feet. If I have no social conscience, I can just build the three bedrooms. But where is the sense of values?”

Some designers have foregone LEED certification, which can be pricey, and put the money into additional environmental measures. And even LEED doesn’t take into account factors like siting a house for a specific climate.

“LEED doesn’t deal with off-gassing, a potential health hazard. I designed a house for a client who wanted no off-gassing. We used low-emission paints, no carpeting, no plywood, no plastic laminates. One thing we were concerned about was finishes for the wood. Lacquer is stable once it’s applied, but during application, it’s one of the most toxic substances. Choosing it, you may be transferring the risk to another human being.”

Happily, there are plenty of ways to improve your home’s efficiency and benefit the planet, as well. One of Llewellyn’s goals for the school is an integrated program that incorporates landscape architecture—everything from adding shade trees, to grading the site to control storm runoff. “Too many people get concerned about the box they live in, and forget about the areas they control up to the property line.” (Those shade trees? They not only beautify the landscape, they also they keep carbon out of the atmosphere and recharge the aquifer.)

“You don’t have to live a Calvinist life to pay for the sins of energy abuse,” says Llewellyn. For example, he suggests installing air-conditioning in a single room, rather than the whole house. “Insulate the room, and don’t use jalousies, which don’t seal as well as other windows. You’ll make it a habitable space that doesn’t use a lot of energy.”

At some point, living sustainably becomes a community endeavor. Llewellyn would like to see more mixed-use neighborhoods that allow people to live, work, and access services without having to get in a car. “It’s not a matter of deprivation,” Stephen Meder concurs. “It’s a matter of how we react as civilizations and human beings. The damage society is receiving is because we haven’t acknowledged our place in the system of nature.”

It’s getting easier, being green. If you’re ready to bring your home more in harmony with the planet, here are some resources to get you started.

The U.S. Green Building Council’s Green Home Guide (www.greenhomeguide.org) is a primer for making dwellings environmentally friendly, complete with checklists for building or retrofitting your home.

The American Institute of Architects’ Hawai‘i Chapter has a website, www.aiahonolulu.org, where you can request information on architects and other professionals who adhere to green practices in design and construction.

Located on the Maui Community College campus, the Sustainable Living Institute of Maui (SLIM) is developing degree programs and internships in sustainable energy and construction, and is a great local resource for information. You’ll find them online at www.sustainablemaui.org.

John Bendon, a LEED-accredited professional and certified energy rater on Maui, and Alex de Roode, executive director of SLIM, will co-host an Energy & Environmental Building Association workshop on Thursday, March 20. Called “Houses That Work,” the workshop is intended for architects, developers, builders, contractors, designers and realtors, but welcomes do-it-yourselfers who’d like to go green. Call de Roode at 984-3379, or email johnbendon@gmail.com for details.

Innovative Design, a Raleigh, North Carolina company, offers “50 Green Strategies That Cost Less.” Visit them at www.innovativedesign.net/guidelines.htm