Story by Sky Barnhart | Photography by Jason Moore | Ron Dahlquist | John Carty

David Cole, president and CEO of Maui Land & Pine-apple Company, Inc., has a “Save Honolua Coalition” sticker on the bumper of his car. Ask him why he’d want to support a coalition that vocally opposes his company’s plans, and Cole would respond, “Because I want to save Honolua, too.”

David Cole, president and CEO of Maui Land & Pine-apple Company, Inc., has a “Save Honolua Coalition” sticker on the bumper of his car. Ask him why he’d want to support a coalition that vocally opposes his company’s plans, and Cole would respond, “Because I want to save Honolua, too.”

Honolua Bay—beloved to surfers, revered by Native Hawaiians, treasured by conservationists—is the azure jewel of the Honolua ahupua‘a (ancient Hawaiian land division) on Maui’s northwest shore. Bordered north and south by basaltic cliffs, the bay is a marine conservation area home to colorful corals, green sea turtles and thousands of tropical fish.

On any given day, the highway’s narrow shoulder is a rainbow of rental cars as visitors trek through the jungle to snorkel the bay’s warm turquoise waters. Continue farther up the road, and a dusty assortment of surfers’ trucks lines the old pineapple road leading down the bluff. At the base of the steep, slippery trail is the right-breaking point surf described by The Encyclopedia of Surfing as one of the best waves in the world.

But the view from inside the wave’s glassy barrel has changed. Thirty years ago, when surfers like Wayne Cochran first surfed Honolua Bay, the view was wave, sky and green cliffs. Today, Cochran laments, the view is changing to golf courses and trophy homes.

Over the last year, Honolua has become a symbol of the island’s struggle with encroaching development. After decades of watching the West Side’s precious coastline vanish beneath new construction, many community members were already on edge when, in January 2007, landowner Maui Land & Pine submitted a proposal to the County’s General Plan Action Committee. The company’s concept for the 583.4 acres at Lipoa Point—the bluff overlooking Hono-lua Bay from the north—included forty luxury homesites mauka (inland) of the highway and a links-style golf course overlooking Honolua Bay.

Suddenly, people who never previously bothered to get involved were speaking out at meetings and writing letters to the editors of The Maui News and Lahaina News, opposing the development. Paddlers and surfers were passing around petitions on the beach. Concerned residents were banding together to educate themselves and the community.

“We were catching the flak for a lot of other developers,” says Teri Freitas Gorman, director of corporate communications for Maui Land & Pine. “They threw us all in the same bucket and said all developers are evil, but we’ve been doing business here for 100 years, and we plan to do business here for another 100 years. The people who work here are Maui people. This is our community. It wouldn’t make sense for us to just come in and trash it.”

Eighteen months ago, Maui Land & Pine Development Coordinator Kalani Schmidt started gathering input from community members about their visions for Lipoa Point. Schmidt met with surfers, bay users, Native Hawaiians, and community organizations to come up with a long-term plan.

A major component of that plan was a surf park, with improvements such as slightly widening and extending the access road, paving it with a light-colored surface so as not to burn surfers’ feet, changing the slope so runoff would be captured in the grasses instead of eroding the cliff, and possibly adding showers, composting toilets and trash cans. The footpath leading down to the bay would’ve remained the same, Schmidt says.

In addition, the proposal included a coastal trail connecting to Kapalua Resort; park facilities and informational signs for bay users; a private campground further north at Windmills Beach; and a Native Hawaiian cultural park with a restored boat ramp, authentic canoe hale (shelters) and Hawaiian education facility—an idea developed with guidance from Lahaina-based Hui o Wa‘a Kaulua (Assembly of the Double-Hulled Canoe).

As for the golf course and the homesites mauka of the highway, that seemed the best way to keep the space as open as possible, according to McNatt. As a publicly owned company, Maui Land & Pine has to ensure that its shareholders’ investments are protected.

But as Gorman points out, “People who choose to invest in our company know our company’s values: one of which is malama ‘aina, care for the land . . . so people who say that we’re just in it for the money; I think that’s not very accurate.”

But once the word was out about Maui Land & Pine’s proposal to the General Plan Action Committee, opposition to the golf course and the homesites grew rapidly.

By March, the Save Honolua Coalition was born. John Severson, founder of Surfer magazine, designed a simple wave-shaped logo, and the group distributed hundreds of T-shirts and bumper stickers. Save Honolua members launched a website, hosted meetings, recruited speakers, circulated petitions and lobbied the Maui County Council to acquire the coastal property at Lipoa Point.

“Who are the golf course and the luxury homes for? They aren’t for us,” says Save Honolua President Elle Cochran. “We are everyday people who really care about the area. . . . None of us are in it for the money. You can fill this room full of money; I’m not taking it over Honolua Bay.”

On April 20, hundreds of Maui residents, schoolchildren and representatives of the Save Honolua Coalition packed Council chambers and gave hours of heart-melting testimony, pleading for the bay to be preserved.

Maui Land & Pine heard the public outcry, and withdrew the plans—despite what Bob McNatt, Maui Land & Pine president of community development, calls “an avalanche of misinformation.” “So we took a step back and said, ‘Okay, we need to go back and meet with the community and decide what really is the best thing for both the community and the company,’” McNatt says.

Now the table has been cleared, and the future of Honolua Bay is wide open again. “We’re starting from scratch,” Gorman says. “We’re open to discussion of all options.”

What about just leaving the area alone? Not possible, Gorman says. “The passive access to the bay that currently exists worked really well for a long, long time.” But we’ve had such a growth in population, and with books like Maui Revealed, spots that were previously known only to residents are now known to anyone getting off the airplane. What was once 40 snorkelers a day is now 400 to 500 snorkelers a day. . . . The passive management that we’ve had in the past—it’s not responsible to continue that without some kind of a plan.”

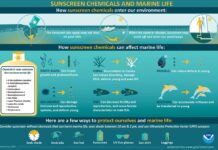

A major factor in the need to “save” Honolua is the health of the bay—health that has declined considerably since the 1990s, according to Katherine Chaston, Ph.D., coordinator of Hawai‘i’s Land-Based Pollution Threats to Coral Reefs Local Action Strategy at the University of Hawai‘i at Maanoa.

“It’s still one of the healthiest and most diverse coral reefs on Maui, but there are ongoing studies through the Department of Aquatic Resources which show that the coral has decreased substantially over time, and the levels of recruitment [young corals] are lower,” Chaston says. “There’s a lot of debate over what is causing the coral decline. . . . We believe it’s sediment runoff from the watershed, but we can’t say definitively.”

A hundred years of agriculture—especially the notoriously fertilizer-greedy pineapple—has exacerbated the amount of runoff entering the water.

“Because Honolua is a bay, it’s not well flushed,” Chaston says. “Sediment can settle and stay in the bay for up to six months, depending on when a storm event occurs. When there’s lots of surf, sediment can get flushed out, but in the summertime, sediment can stay on corals and smother them.”

Sediment can also turn the water chocolatey brown, reducing the amount of light seeping through to the coral. The effect is what Chaston calls a “double whammy”: the sediment smothers the coral and blocks the light it needs to reproduce.

“We are at this critical point where we really need to do something,” she says. “The main thing is to try to stop these sediment runoff events.”

The situation is likely to improve now that pineapple is no longer grown in the area. But more importantly, any future development must incorporate low-impact design to minimize runoff, Chaston says. Not a problem, says McNatt—Maui Land & Pine already incorporates best-management practices throughout all its projects.

No development is acceptable if it’s north of Honolua Ridge, says Save Honolua board member Nikki Stange. While the coalition is still “engaged in research and education” at this point, Stange says, the one clear goal is to see the land preserved as open space.

Toward this end, the Maui County Council has set aside $1 million as seed funding to purchase the coastal land and is holding regular meetings with Maui Land & Pine to discuss options such as converting much of the land into a conservation easement. Speaking at the coalition’s June 12 meeting, Tavares warned the packed crowd that acquiring the land would only be the first step—then there must be a management plan.

Gorman is doubtful whether the County has the resources to manage such a fragile, high-use area. “I think the County would be the first one to agree with that,” she says. “And so what we’d have to do is a little out-of-the-box thinking . . . maybe some kind of a corporate/private partnership.”

Longtime Maui surfer and board shaper Les Potts would like to see the area become a coastal land trust. “I disagree with the coalition’s plan to have the County buy the property—then it’s public,” Potts says. “Look at the trails down the cliff. There are enough lawsuits waiting to bankrupt the County—unless they build stairs, and most surfers don’t want that. . . . Get the land put into a coastal land trust. That way you don’t buy the property, but you buy the development rights. You preserve the property and there’s not as much liability because technically it’s still private property.”

Historically, the area has been used in many ways: as a thriving fishing village and for growing kalo (taro) and sweet potato prior to European contact; for cattle and coffee production in the late 1800s; for growing pineapple throughout the twentieth century. In 1946, a tsunami destroyed the remaining community in Honolua Valley. Thirty years later, Kapalua Resort was developed. The same year, the first Hokule‘a sailed out of Honolua Bay on her epic voyage to Tahiti, giving strength to the growing reemergence of Hawaiian culture.

David Kapaku’s family has lived at Honokohau, about four miles north of Honolua, for generations. An ordained minister with a doctorate degree, Kapaku sees Maui, and all of the Hawaiian Islands, as a spiritual body.

“Honokohau is the softest part of the head, where the pulse beats,” Kapaku says.

“Honolua strengthens that passage of breath. Once you take that strength away, you’re in trouble. That’s why we have to save Honolua. If we shut off the breath of God, Maui will die.”

Maui Land & Pine understands its “ingrained responsibility” to care for the land, McNatt says. With its malama ‘aina cornerstone, the company has initiated conservation projects such as recent efforts to restore a thirty-acre dry-mesic native forest in fallow pineapple fields above Honolua Bay.

“There’s no two sides of the fence here,” Schmidt insists. “Everybody wants the same things for the bay, so how are we going to get there? We need to leave the pilikia [trouble] and move forward.”

Elle Cochran is in agreement that the issue should not be an “us versus them.” “It’s all of the community involved,” she says. “The support from the community has been tremendous. Now we need to get everyone’s input to form an overall concrete vision.”

Kapaku proposes that one thing should be built immediately at Honolua: an altar. “I propose we ask people from all over Maui to come and bring a pohaku [stone] from where they live, and we will build the altar,” he says. “Then we’ll see the spiritual rise, and Honolua—and Maui—will be saved.”

Ancient Hawaiians in the area laid stones with their hands, Kapaku says. “It is our kuleana [responsibility] to put our hands on the stones so our kupuna [elders] can let go. But we tell them, ‘Don’t let go yet, leave your hands there and teach us how to do it correctly.’”

To learn more about efforts to save Honolua Bay, visit Maui Land & Pine’s website at www.malamahonolua.com; or the Save Honolua Coalition website at www.savehonolua.org. The coalition meets every Tuesday from 6:30 to 9 p.m. at King Kamehameha III Elementary School Cafeteria at 611 Front Street in Lahaina. In addition, Chaston’s report on the synthesis and analysis of land use and marine information in Honolua Bay will soon be available to the public. For more information, e-mail to: chaston@hawaii.edu.