Gonsalves, Irwin, and Stoltzfus believe that biotechnology can be a boon for farmers, helping them produce more with less. “Genetic engineering isn’t the silver bullet; it’s just one tool,” says Stoltzfus. “Pesticides are another tool, as are organics. There are many solutions and we need all of them. The goal is the same: sustainable agriculture.

“Farmers are probably the foremost environmentalists out there,” he says. “They won’t poison their ground for a short-term gain. They’re looking to preserve that farm for the long term, to pass on to their kids and grandkids. The land is our lifeblood and we want to make sure that it’s productive.”

If all of this is true, why did so many people rise against GMOs?

Alika Atay is a sweet-potato farmer and outrigger-canoe coach whose roots run generations deep on Maui. He’s a member of the SHAKA Movement (the nonprofit’s acronym stands for Sustainable Hawaiian Agriculture for the Keiki [children] and the ‘Aina [land]), and one of five cosigners of the GMO moratorium. In the days leading up to last November’s election, the native Hawaiian’s flowing white hair and beard became a familiar sight on the news. When I ask him what motivated him to join SHAKA, he evokes the state motto: Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono. “The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.”

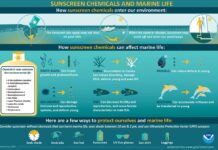

“We need to look at what we are doing to our ‘aina,” says Atay. “We live on an island with finite resources. Forty years ago, Maui ag companies sprayed heavy chemicals onto pineapple. They leached into the soil, down into our water table. Forty years later, the well at Hamakuapoko is still tainted.

“Now when I see excessive spraying, I wonder: When will it seep into our fresh water? When the big rains come and wash through the Kihei fields, where does the runoff go? To our ocean where our children surf and play, where we natives go and collect our food. So, is it safe?”