Story by Rita Goldman

Macario Pascual was five years old in 1962, when he and his mother left the Philippines to join his father at Pu‘ukoli‘i Village, a plantation camp run by Pioneer Mill. “I couldn’t speak the language,” he says. “I didn’t have a lot of friends.” But Macario could draw. “By third grade, I was good at it; that’s how I started making friends.”

Art became the bridge between his old life and the new. Walking home from school, he would pass the studio of artists Stephen Sands and Cecilia Rodriguez. “I would see their paintings through the screen, and my curiosity got the best of me. They welcomed me in. Stephen was a velvet artist, and yes, I started with velvet. With a really good velvet painting, you can still feel the nap. It’s like old masters’ paintings, with many thin layers of paint.”

By the time he was twelve, Macario was selling his work under Lahaina’s banyan tree, alongside older and more accomplished artists. “I had my first show at Lahaina Arts Society when I was seventeen. After the show, I told my dad, ‘This is what I want to do.’ I was bracing for the worst. My father had only a fourth-grade education. He came in 1946 with the last big group of sakadas [Filipino men hired to work on Hawai‘i’s plantations]. He came for a guaranteed paycheck, and he’s talking to his oldest boy — who wants something that’s not a secure occupation. After a quiet pause, he said, ‘Okay, but you know it’s a tough life.’ I think he saw how hard I worked, how art was my passion.”

With the help of an art scholarship, Macario attended the University of Hawai‘i, graduating with a BFA in design. His sophomore year coincided with the seventieth anniversary of Filipino immigration to Hawai‘i; it pulled him back to his roots. “The research I did opened my eyes. I started thinking, ‘I want to paint people like my dad.’”

Macario started filling his canvases with the people and scenes he’d grown up surrounded by: brown-skinned men and women laboring in the fields, hands in thick work gloves cutting the cane with machetes, backs stooped to gather the stalks to load onto cane-haul trucks, anonymous workers in head-to-toe clothing that protected them from cane spiders and centipedes in the hot Lahaina sun.

His work caught the eye of Richard Nelson, an artist and educator who was then executive director of the Wailea Arts Center, which was owned by Alexander & Baldwin — one of Hawai‘i’s “Big Five” corporations and the parent company of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar. When the corporate offices decided to commission a major art show in Honolulu, celebrating sugar in Hawai‘i, Nelson recommended Macario. “He was just a kid, right out of college, but he was a natural. He has always been a colorist, picking the time of day when the sun has a warm light. His work hit a responsive chord with A&B.”

Nelson saw in Macario’s depictions of plantation workers the kind of empathy and affection the French Realist Jean-Francois Millet invested in his painting The Gleaners (1857). “The idea of bringing dignity to a [working-class] level of society, showing common, ordinary scenes . . . Realism went against what was then the status quo and changed the definition of what is art,” says Nelson.

Nelson saw in Macario’s depictions of plantation workers the kind of empathy and affection the French Realist Jean-Francois Millet invested in his painting The Gleaners (1857). “The idea of bringing dignity to a [working-class] level of society, showing common, ordinary scenes . . . Realism went against what was then the status quo and changed the definition of what is art,” says Nelson.

But while Macario was establishing himself as an artist who could capture plantation life with richness and depth, dignity and compassion, Hawai‘i’s sugar industry was struggling against increasing competition. When Pioneer Mill closed in 1999, it left HC&S, in Maui’s Central Valley, the state’s last surviving sugar plantation. And as HC&S mechanized, says Macario, “My source of human subjects disappeared.”

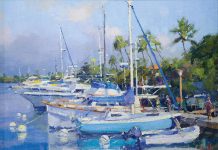

He began to focus more on landscapes, returning to an early interest in plein air. Instead of sketching or photographing his subjects and going back to the studio to paint, Macario would set up his easel out on location and work to capture the landscape before the sunlight changed. He participated in plein-air shows around the county, and in the Maui Plein Air Painting Invitational, which each year brings in respected artists from Hawai‘i and the mainland for a week of painting outdoors, with the public invited to watch.

He began to focus more on landscapes, returning to an early interest in plein air. Instead of sketching or photographing his subjects and going back to the studio to paint, Macario would set up his easel out on location and work to capture the landscape before the sunlight changed. He participated in plein-air shows around the county, and in the Maui Plein Air Painting Invitational, which each year brings in respected artists from Hawai‘i and the mainland for a week of painting outdoors, with the public invited to watch.

“Plein air has made me a better, more flexible artist,” says Macario. “The biggest difficulty is, there’s so much information, and things are in constant motion—people, clouds, trees. . . . It’s hard to process it all. When I’m looking at a photo, I tend to paint almost everything the photo gives, because it’s not moving. With plein air, I’m taking notes. I decide how much or how little information I’ll show.”

But he wasn’t painting what he loved best: the people and activities of his childhood. “I thought that era was gone,” he says. Four years ago, a collector changed his mind. “My biggest collector,” he recalls. “She felt that I should do what I know and hold dear. She gave me a grant to do a theme I had talked about, plantation life revisited. Using models and props, old photos and drawings for reference, I came up with seven large paintings; each has a story. That’s when I realized that I can go back. I can’t paint workers in the fields anymore; the fields are gone. But when I was painting in the late seventies, eighties and nineties, I was focusing on the work, and not showing my subjects’ faces. I want to go back and paint the faces, to learn and be inspired by who they are, where they came from, what they felt.”

At Plantation Days, an annual celebration of Lahaina’s past, Macario found himself reconnecting with folks he hadn’t seen in years, and having his paintings viewed by people he’d never met. “It dawned on me that a lot of Lahaina kids have no idea what that smokestack stands for. They don’t know that there were buildings around it, and trucks, and fields of green cane blowing in the wind. These kids will inherit their parents’ and grandparents’ photos and memorabilia, and be one step away from tossing them.” He’s begun to ask families to let him explore their photo albums, so that he can tell their stories through his art.

“Maybe I’ll recreate a photo as a painting, or incorporate aspects of it into my own story. Photos get handed down, but they’re easy to throw away if you don’t know the stories behind them. A painting is something you can hold onto. You might give it away, or sell it at the flea market, but the story gets to live on. Maybe the kids will discover the story and appreciate where they came from and what they have. I think that would be pretty cool.”