Rita Goldman| Photography by Cecilia Fernández Romero | Nina Lee | Jason Moore | Marata Tamaira

Abigail Romanchak

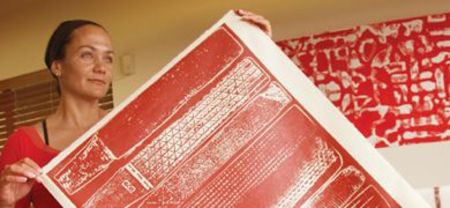

Abigail Romanchak

In her authoritative Hawaiian Dictionary, Mary Kawena Pukui defines maoli as “native, indigenous, aborigine,” and also as “genuine, true, real.” For artists of Hawaiian ancestry, the meanings are inextricably interwoven.

You’d never guess by looking at Abigail Romanchak that Hawaiian blood flows through her veins. Her art is another story. One of Maui’s most accomplished young artists—of any ethnicity—Romanchak employs Western techniques and materials to explore the riches of her maoli heritage.

“My sources, my inspiration, link back to my ancestors, who happen to be Hawaiian, Ukrainian, Spanish, French and English,” says Abigail. “But I was born and raised here. I am much more familiar with, and closest to, my Hawaiian roots.

Romanchak was among the artists represented in last May’s Maoli Arts Month—a citywide celebration that featured works by Native Hawaiians at galleries across Honolulu. Her piece is a stunning depiction in wood and paper of the corded framework for a feathered cape. Romanchak had seen examples of such framework in Hawaiian art-history books, and actual netting created by contemporary Hawaiian cape makers. The artist in her saw a metaphor. “I looked at the beautiful netting, naepuni, and thought, This is the most important part. It’s the foundation that holds everything together.

“What makes me a Hawaiian artist? That’s the first question I had to face for my MFA,” she says. For her thesis, Romanchak created an installation she conceived as a dialogue between herself—a contemporary printmaker—and traditional makers of kapa, Hawaiian bark cloth.

“I took something usually hidden, the watermark beaten into kapa, and enlarged it so the viewer couldn’t help but wonder what it is. I produced such a piece in Waimea at Piko, a gathering of indigenous artists. I was in the same room as traditional kapa makers, using traditional watermarks, but I was using Japanese kozo paper, Western oil-based etching inks, and printing with a press. When I finished, I thought, What is someone like Auntie Marie going to think? Marie McDonald is a kupuna [elder]; she’s probably the best kapa maker in the state. She instantly recognized the marks. She said, ‘Oh, this is fabulous! I love it!’

“For the culture to live,” says Abigail, “we need to talk to our kupuna, look at the museum artifacts, then move on.”

“Would your art be Hawaiian,” I ask, “if you were born and raised here, but had no Hawaiian blood?”

“I don’t know,” she admits. “But it upsets me when non-Hawaiians paint or sculpt Hawaiian themes, but aren’t in the least bit educated in the culture. I’m a printmaker—I use an etching press used in the eighteenth century. But I studied kapa making. I had to know the tools. I don’t care if people call me Hawaiian or not, so long as my work has integrity.”