Story by Heidi Pool | Photography by Zane Mathias

When Zane Mathias suggested we meet at Hanzawa Store in Ha‘iku so I could follow him home, it seemed I was in for an adventure. My intuition was correct—it’s the most fascinating house I’ve ever seen.

When Zane Mathias suggested we meet at Hanzawa Store in Ha‘iku so I could follow him home, it seemed I was in for an adventure. My intuition was correct—it’s the most fascinating house I’ve ever seen.

Kaupakalua is a two-lane country road with plenty of hairpin turns as it winds its way around Ha‘iku’s hills and ravines. Leaving the road, our cars crunch down a long gravel driveway, past brilliant red torch ginger, shiny anthurium, and thick rain-forest vegetation, eventually arriving at a clearing where we park. A lanky six-footer, Zane has a lengthy white ponytail and beard to match. His youthful exuberance belies his seventy-five years. Like a child eager to show off his room, Zane leads me up a set of concrete stairs to the lanai, where we’re joined by his wife, Beth, who, at four feet, ten inches, is as diminutive as Zane is rangy.

The first indication of the delights in store for me is the coffee table in their outside entertainment area. The base is five iMacs in different colors—tangerine, lime, strawberry, blueberry, and grape—arranged in a circle and topped with a pane of glass. It’s Zane’s interpretation of Apple Computer’s “Yum” poster, created in the late 1990s when the fruit-inspired iMac was introduced. Displayed in the computers’ screens are photos of friends, family members, and pets. “If we have visitors coming and I have a photo of them, I can pop their picture into the monitor as sort of a welcome gesture,” Zane tells me. “I change the pictures all the time.”

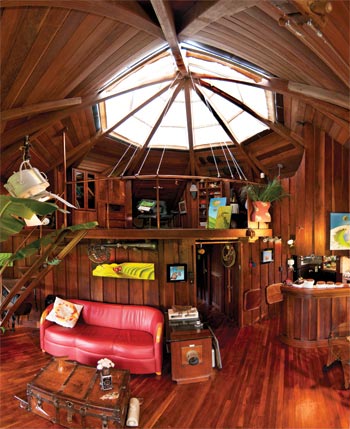

The house Zane and Beth have shared since 1989 with their twenty-one-year-old cat, Beanbag, is 710 square feet, octagonal, and made entirely of eucalyptus and glass. From the living/dining area inside the home, you can see into all the rooms on the main level, as well as the loft above. Zane says: “It’s like living on a boat that’s run aground in the jungle.”

Zane and Beth have adapted remarkably well to living in a house with a tiny footprint. “When you live in a small space, everything in it has to be something you actually use,” says Beth, “and it’s all about creative storage solutions. My biggest concern when we moved in was, ‘Where will I put all my stuff?’”

In the compact kitchen, Beth has everything at her fingertips. To compensate for the lack of drawers, Zane mounted frequently used items on the ceiling; cooking pots and lids, plastic storage containers, and even a silverware caddy hang overhead. Beth stands on a stool to reach them. “I love watching my wife in the kitchen,” Zane says fondly. “She’s like a lazy Susan as she turns this way and that.” Beth adds, “It’s the best kitchen I’ve ever worked in. I used to have a lot of items in storage, but I got rid of them, since there’s just no space here for things I don’t use.” They keep a minimal number of dishes, and when guests come for dinner, Zane and Beth wash plates between courses.

Living in Ha‘iku presents additional challenges for the couple. They’ve had to take measures to keep bugs from invading dry goods and appliances. Zane made a toaster cover from scrap wood, using an old camera for a handle, and the plastic storage jars mounted to the kitchen ceiling contain sugar, flour, rice, pasta, and Zane’s beloved Easy Mac. Every Ha‘iku householder knows plastic jars are one of the better means of protection, but not everyone affixes them to a ceiling.

Bugs aren’t the only nuisance of rain-forest living. A fine-art commercial photographer, Zane had to figure out a way to protect his camera lenses from the effects of humidity. “Moisture is the bane of any Hawai‘i photographer’s existence,” he says. “It causes fungus to form on the lenses, which eats the glass and ruins them. But I’ve conquered it by putting a sixty-watt incandescent light bulb into this old steamer trunk that functions as our coffee table, as well as a storage compartment for my cameras. The bulb creates its own weather pattern, circulating air throughout the trunk that keeps my lenses dry.” Another old camera and a Zulu warrior’s wooden headrest, found at a Lahaina swap meet, are mounted on top of the trunk, serving as handles. “Multipurpose furniture is essential in a small space,” he adds.

Zane is reluctant to be called an inventor. “I take great pride in giving new life to obsolete items, and modifying things to make them more functional,” he says. He collects antique brass musical instruments and transforms them into light fixtures. Illuminating the dining area is an old baritone Zane seamlessly welded to a morning-glory gramophone horn into which he installed lightbulbs. It’s adorned with more than 900 old Hawai‘i bottle caps flattened, strung, and painted to resemble an ilima lei, and a “maile lei” made from soda cans cut and manipulated to look like flowers. Above the sofa is another of Zane’s lighting creations; he made it out of an old French horn.

Zane and Beth took the concept that began in the kitchen and applied it to the bedroom. Rows of baskets and storage compartments mounted on the ceiling contain paper goods, clothing, sheets, tools, and other household items. “It shrinks a space when there is too much clutter on the floor,” Beth explains.

To keep their vacuum cleaner out of the house, Zane created what he calls a “poor man’s central vac system.” The unit is in an adjacent workshop, connected by hoses that run throughout the main floor of their house. “One of these days I’ll connect it to the upstairs so Beth doesn’t have to haul a vacuum up [to the loft],” he says. “Zane is always creating things,” Beth adds. “Anything he decides to put his hand to, he’s successful, but it’s never in the conventional way.”

Adding to the home’s quirkiness is the fact that all interior partition walls are curved, making furniture and artwork placement inherently challenging. Zane built a pair of curved wooden bookcases in the bedroom that separate to reveal a pull-down ironing board. He bends plastic or precisely cuts wood to make bowed picture frames. “Having curved walls makes you think differently.

“This house helps me brainstorm; it’s my idea chamber. I haven’t changed the house nearly as much as the house has changed me,” Zane says, “and I enjoy thinking small.” Beth is the pragmatic one, handling the couple’s finances, and it’s fortunate she does. “Zane didn’t realize until he was in his fifties that you actually have to pay for electricity,” she says ruefully.

I ask how their landlords feel about the modifications they’ve made to the house. “I love our landlords,” Zane enthuses. “They let me do whatever I want. They treat us like they’re the renters instead of the other way around.”

Besides the curved bookcases, the pièces de résistance for Beth are Zane’s custom-made shades covering the expansive octagonal window above the loft. She arrived home from work one evening to find him furiously measuring, cutting, and sewing canvas into eight pie-shaped segments. The shades are operated by an ingenious system of weights, ropes, and hooks. “Being married to Zane is like living with a thirteen-year-old,” laughs Beth. “He believes it’s his responsibility to make my life one continuous adventure.”