Story by Paul Wood

You don’t have to be very old to remember when bomb blasts shook the windows and rattled the silverware of homes all along South and West Maui. Anyone conscious during the late 1970s can recall with a thrill the rising up of Hawaiians and their supporters to demand that the bombing stop. Today, schoolkids learn about the Hawaiian Renaissance, when the indigenous people dared to tell the U.S. Navy: “It’s not okay to destroy a Hawaiian island. Put it back the way you found it.” To the uninformed, it looks as though the Navy fixed a few things and left. The truth is more complex.

Kaho‘olawe is the eighth largest Hawaiian island, one of four that constitute the County of Maui. It sends no representatives to the state legislature, though, because Kaho‘olawe is both uninhabited and uninhabitable. Too much UXO — unexploded ordnance. The United States began bombing the island during the 1920s, not long after territory-hood, escalated during World War II, then increasingly through the Cold War. Today you can’t stick a shovel in the ground without risk of blowing up. Even in areas cleared to the depth of four feet — 9 percent of the island — erosion exposes previously undiscovered bombs. And erosion continues to despoil Kaho‘olawe. Nearly two million tons of soil are washed into the sea each year, leaving behind slick slopes of hardpan, barren and bloody red.

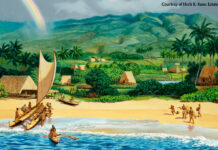

Yet this callused and stern terrain includes some 3,000 features listed with the National Register of Historic Places. From the summit of its single volcanic peak — one-seventh the height of the mountain six miles away, sunrise-blocking Haleakala — you can observe the winds and currents that rush between the islands. Kaho‘olawe was once a navigational training center for Hawaiians; its name was Kanaloa, god of the sea. Some 800 documented archeological sites provide evidence that people lived, fished, farmed, and worshiped here before Western contact.

Kaho‘olawe environmental disaster started in 1793 with the introduction of goats, which scrambled over the fragile dry hillsides, gobbling native vegetation for the next sixty years. In 1858, the Kingdom issued ranching leases for the island. The ranchers planted kiawe (mesquite) trees, which produced good feed, but sucked up groundwater and desiccated their surroundings. By the early 1900s, not even famed Maui cattleman Angus MacPhee could make his Kaho‘olawe ranch viable. Knowing that U.S. warships had been doing target practice nearby, he subleased his ranch to the Navy in May 1941. Seven months later, all hell broke loose at Pearl Harbor.

In 1953 President Dwight Eisenhower ordered the entire island reserved for U.S. Navy purposes. But he also directed the Navy to eradicate all cloven-hoofed animals, cooperate with reforestation efforts, and “when the island was no longer needed . . . and without cost to the Territory of Hawaii, make the island safe for human habitation.”

There’s the rub. The possibility of making Kaho‘olawe safe diminished with each ensuing conflict. During the Korean War the Navy strafed the island and airdropped bombs. The Vietnam era required mock surface-to-air bombing targets. The Cold War demanded increased armed readiness. The island became a kind of mayhem museum, with bombs as large as 3,000 pounds jabbed into the earth. In 1965, a medley of megablasts reconfigured the coastline and further compromised the island’s ability to retain rainwater.

Effective local resistance started in 1976, when a crew of native activists from Maui and Moloka‘i crossed the channel and trespassed on the island. The Navy chased them away, but two young defiants from Moloka‘i — Walter Ritte and Emmett Aluli — hid in the shrubbery. Arrested and released, Ritte and Aluli led a second invasion. This time, the Navy blinked. It agreed to allow limited access for cultural purposes. Then Aluli filed a federal suit to stop the bombing altogether. As that suit simmered, Moloka‘i-born musician and orator George Helm spoke to state legislature, procuring a resolution on behalf of Kaho‘olawe that he took to an audience with President Jimmy Carter. One month later Helm and Maui youth Kimo Mitchell staged a nighttime illegal access of Kaho‘olawe and died at sea. Their deaths sparked conspiracy theories and made them martyrs to the cause.

Still the Navy invited its RIMPAC allies to join them in bombing the island. In 1980, Aluli’s lawsuit succeeded, resulting in a historic consent decree and order. It required the Navy to protect cultural sites, clear surface ordnance from 10,000 acres (about a third of the island), limit the bombing to one-third of the island, and allow monthly accesses (huaka‘i) to a nonprofit, essentially Hawaiian organization called the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana (family). The PKO set up its base camp on the island’s north shore, at Hakioawa, an area rich with archeological sites. These monthly accesses required swimming in from offshore boats, raw camping, and immersion in Hawaiian ritual and sweat labor, and still do to this day.

Pat Saiki stopped the bombing in 1990. Taking advantage of election-year finagling during the George H.W. Bush Administration, Big Island-born U.S. Congresswoman Saiki cut a deal that compelled Washington to give Kaho‘olawe back to the State of Hawai‘i.

In 1993, the deal became law. Guided by the deft U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye, President Bill Clinton signed a Department of Defense Appropriations Act that included a memorandum of understanding about UXO cleanup and ecological restoration. The Navy killed every goat on Kaho‘olawe and prepared to unbomb the island it had bombed for decades. The limit on what the Navy could do was fixed by the size of the Congressional appropriation: $400 million, minus $44 million set aside for the State of Hawai‘i.

Given this $44 million trust fund, the legislature created a state entity — the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission — to manage the island and its surrounding waters. In 2014 KIRC had seven commissioners, an executive director, and a staff of fewer than twenty employees. Since the end of the Navy’s cleanup operation in 2004, KIRC has spent about $3 million a year to carry out its mandate, and now that fund is gone.

“We’re trying to create a watershed that hasn’t been there for 200 years,” KIRC director Michael Naho‘opi‘i said recently. “If we can replant the hardpan, rain will go into the ground rather than run off. When that happens, people can live again on the island.”

But such work, much of it done by volunteers in blazing sunlight and sandblasting winds, requires ingenuity. If you can’t dig a hole without wondering whether you’re about to blow your head off, you have to invent aboveground methods of reforestation. You make a circle of stone in the right spot, and let winds drop topsoil into the ring, ready for a potted plant. You chainsaw kiawe trees out of a natural basin, shred the trees, and plant native shrubs in the mulch. Soon the basin begins to hold runoff, forming a little wetland. You build a water-catchment system that manages to collect half a million gallons a year from the usually rainless sky, then run drip lines into mile-long, rock-lined mulch beds planted with indigenous dryland forest species. You stop runoff with rock-filled burlap dams. You fly bales of native pili grass from Moloka‘i, fix the bales on top of slick red hardpan, cover them with chicken wire so they won’t blow away, and pray for rain. Naho‘opi‘i keeps photos of these modest successes on his smart phone. A row of nine little rooted shrubs: “See? The greening of Kaho‘olawe is happening a lot faster than I thought it would.”

Naho‘opi‘i is a hefty man with a robust and smiling disposition. “That’s my life — to figure ways around things,” he says. And most of that figuring has focused on the Target Island. As a Kamehameha Schools student in 1981, he went on the first access that allowed teenagers. After graduating, he attended the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis and trained as a submarine officer. In 1993 he got a call from the admiral at Pearl Harbor, who was looking for a native Hawaiian line officer to serve as commanding officer for Kaho‘olawe during the most contentious days of PKO agitation. His main directive from on high was this: “I don’t ever want to see Kaho‘olawe in a bad light.”

When Naho‘opi‘i, in uniform, met with the PKO activists at their Hakioawa base camp, he recognized many of them as his former schoolmates. From that point till today he has remained involved with and committed to both sides, both the grassroots and the governmental. He is the bridge man. In 1995 he left the military and spent ten years managing the island cleanup as a civilian. He worked with Parsons and UXB International, the companies contracted by the Navy to get the work done. He became mo‘olono, a priest of Lono, to perpetuate the annual Makahiki ceremonies on Kaho‘olawe with the PKO. He later accepted the KIRC director position, taking “a huge pay cut, because I wanted to do something meaningful in my life.” He smiles as he admits that his is a difficult job, begging the legislature for money, and fielding the commissioners’ frustrations. “I get beat up a lot in meetings.” But he’s committed to the cause. “I just couldn’t leave the island the way it is.”

“The way it is” is far from ideal. The Navy pledged to clear 100 percent of the surface and 30 percent of the subsurface. After more than seven years of earnest, almost frenetic efforts, the results were, correspondingly, less than 75 percent and less than 10 percent. The work involved flotillas of contracted helicopters moving hired personnel and equipment daily between Kahului and Kaho‘olawe. The paperwork was monumental — environmental impact studies, transects, data processing. A traditional cleanup will focus on 500 acres, says Naho‘opi‘i, but this work encompassed a 28,800-acre island. They mapped and studied thousands of 100-meter-square grids for the state to prioritize, and documented more than 800 archeological sites.

Then the whole operation simply ran out of money. For Congress and frankly most everyone else, the attention has wandered away to other matters.

The Navy’s website says its operation purged more than 100,000 ordnance items, 10 million pounds of metal, and 14,000 tires; installed more than 8,000 boundary posts, a 9.6-mile road (cost: $8.8 million), and some $10 million in equipment and facilities, all of which it handed to KIRC in the official transfer of access control at the end of 2003. At the transfer ceremony, staged on the grounds of ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu, Rear Admiral Barry McCullough announced: “I am very pleased with the quality of the work done here. The efforts of all the workers and this team will allow the State of Hawai‘i to provide safe, meaningful access to the island for what the State has in mind.”

Michele McLean presently serves as chairwoman of KIRC. By day she is deputy planning director for the County of Maui and is a veteran of government work on county, state, and federal levels. Reflecting on KIRC’s use of its trust fund, she states firmly that she has never seen more efficient and effective use of appropriated moneys. But the island is still derelict.

Now that the federal trust fund has run out, it is time for the state legislature to pony up. The response has been feeble — $2 million total for 2016 and 2017, a sum that cuts KIRC’s meager budget by two-thirds. This will certainly necessitate layoffs in its little staff of a dozen-and-a-half, and cripple the commission’s ability to recruit and transport volunteer labor. Everyone who visits Kaho‘olawe is moved by its rugged beauty, its timeless aura, and its great need — but few can make the trip. So KIRC has created a public site next to the Kihei Small Boat Harbor, where it stages monthly public-awareness events, and it is appealing for financial support. In one month last summer, KIRC raised $38,000, well short of its $100,000 goal.

The newest KIRC commissioner, appointed in Fall 2014, is Hokulani Holt, who in previous years helped the PKO establish cultural protocols for visits to Kaho‘olawe. When she joined the commission, she says, “I was shocked at the finances. To spend down the trust fund to almost nothing, and to have no other plan! I went, ‘I must be missing something. Everyone thinks this is okay.’”

KIRC chairwoman McLean expressed a similar puzzlement. The federal trust fund was never meant to be an endowment, but the state could have managed the money in some way other than to spend it down. Likewise, the state could have refused to take the island back in such ragged condition. “But we accepted it,” she said. “Now [if we protest to the federal government] we don’t really have a leg to stand on. The legislature, the administration, the activists, they were all so delighted to get it back that they didn’t say, ‘Wait a minute. . . .’”

KIRC’s mood, though, is not blameful, nor is it determined that UXO will ever be cleared from the island. “It would [cost] hundreds of millions, if not billions, to be able to say that the bombs have been substantially cleared. Certainly we will never be able to say that the waters are safe,” says McLean.

More important: habitat restoration. Activists envision Kaho‘olawe as a refuge for endemic plants and wildlife. A sanctuary for seabirds, now that rising sea levels are drowning nesting sites on northwest seamounts and islets. An underwater shelter for the replenishment of fish populations. A living site of traditional Hawaiian culture. A model of alternative energy practices. Above all, a caution, and a reminder about right living.

“All the islands are like family members,” says Holt. “How can I ignore my grandparents and set them adrift? Kaho‘olawe is not just for the Hawaiians. We as humans need a wild place. Kaho‘olawe is for all of us.”

Ironically, manmade disaster has spared the island from the creeping sprawl of civilization. In time, Kaho‘olawe might become something other than an emblem of failure — a symbol of hope.

Get Involved

Make a charitable donation to the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission, or to the Kaho‘olawe Rehabilitation Trust Fund at GoFundMe.com/AlohaKahoolawe2015.

Visit KIRC’s website for:

- a wish list of equipment to support KIRC’s mission;

- details on attending Mahina‘ai, KIRC’s free monthly educational hikes, Hawaiian music, and more;

- free teaching materials, chants and historical documents.

Schedule a workday with your club, classroom or other group at KIRC’s Kihei site, where Kaho‘olawe experts are developing a community learning space.

Testify to support KIRC funding when the state legislature goes into session in January. Look for announcements at Facebook.com/KircMaui, and register for hearing notices and submit testimony at Capitol.Hawaii.gov.

Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission

811 Kolu Street, Suite 201

Wailuku, HI 96793

808-243-5020 | Kahoolawe.Hawaii.gov