In the 20th century, the only references to Hawaiian hale could be found in the far corners of hotel properties, structures used for massage huts or bars. But since 2002, a reemergence of hale building has been taking place on Maui, and these structures can once again be seen around the island. Palani Sinenci is leading this hale-building renaissance. Since retiring from the Air Force after a 29-year career as a maintenance manager on military aircraft, Sinenci is sharing his ‘ike (knowledge) to revitalize the skill of hale building.

In the 20th century, the only references to Hawaiian hale could be found in the far corners of hotel properties, structures used for massage huts or bars. But since 2002, a reemergence of hale building has been taking place on Maui, and these structures can once again be seen around the island. Palani Sinenci is leading this hale-building renaissance. Since retiring from the Air Force after a 29-year career as a maintenance manager on military aircraft, Sinenci is sharing his ‘ike (knowledge) to revitalize the skill of hale building.

Quoting the 19th-century Hawaiian historian David Malo, Sinenci explains the traditional significance of the Hawaiian hale: “Three things were important for the well-being of the kanaka maoli [original Hawaiian people]: The canoe for travel, fishing and warfare, the ‘aina [land] for planting taro, and the hale that provided the place to rest.”

“We have seen the revitalization of the sailing canoe and farming taro among our people,” he continues. “Now, the revitalization of the hale fulfills the last of the three requirements for a complete and healthy Hawaiian lifestyle and culture.” He believes perpetuating these foundational elements will promote pride among the Hawaiian people.

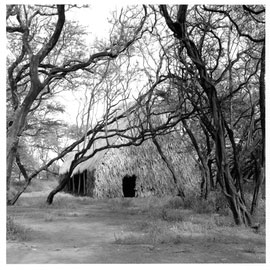

In ancient times, the Hawaiian village consisted of many different types of hale. The kane (man) built separate hale for himself and his family in accord with the ancient kapu system, which stipulated, for example, that men and women were not allowed to eat together. Different hale also provided places for different kinds of work and rest: hale ali‘i (chief’s house), hale mua (men’s eating house), hale ‘aina (women’s eating house), hale noa (where the family mingled and slept), hale ku‘ai (trading house), and halau hale, which stored the canoe. The structures were made from ocean-cured ‘ohi‘a logs lashed together with sennit. The roof was a thick layer of pili-grass thatching, and the floor was a mosaic of smooth ‘ili ‘ili (small stones) gathered from the shoreline. The builders used the horizon as their level, and their fingers, hands, and arms for measuring.

In ancient times, the Hawaiian village consisted of many different types of hale. The kane (man) built separate hale for himself and his family in accord with the ancient kapu system, which stipulated, for example, that men and women were not allowed to eat together. Different hale also provided places for different kinds of work and rest: hale ali‘i (chief’s house), hale mua (men’s eating house), hale ‘aina (women’s eating house), hale noa (where the family mingled and slept), hale ku‘ai (trading house), and halau hale, which stored the canoe. The structures were made from ocean-cured ‘ohi‘a logs lashed together with sennit. The roof was a thick layer of pili-grass thatching, and the floor was a mosaic of smooth ‘ili ‘ili (small stones) gathered from the shoreline. The builders used the horizon as their level, and their fingers, hands, and arms for measuring.

Sinenci doesn’t recall seeing any Hawaiian hale while he was growing up in Hana. When his sixth-grade class at Hana Elementary School was assigned book reports about aspects of Hawaiian culture, however, he chose to write about hale. Standing in front of his class and presenting his findings during show-and-tell, Sinenci taught his peers about their ancestors’ architecture. This became the foundation for his curiosity, passion, and teaching.

Ua Ku ka Hale