Interview by Catharine Lo

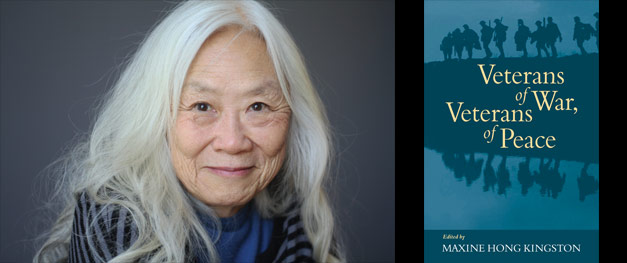

“How can they ever be the same?” asks Maxine Hong Kingston, referring to individuals recovering from the traumas of war. The award-winning writer established the Veterans Writing Group in Northern California in 1993; it has helped more than 800 men and women come to terms with their experiences. Last year, Kingston published Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace, a collection of stories and poems by those who have been through war’s hell and found the strength to tell about it.

This July, Kingston will cohost a writing and meditation retreat in Hana for veterans and their families. She shared her thoughts on how writing can heal, and the journey toward nonviolence.

Can you describe the retreat?

We find a place where people can enjoy the beauty of their surroundings, to return to the idea that the world can be a lovely place. This is why Hana is perfect. The journey into the country to be closer to the ‘aina — that in itself is an amazing healing experience.

There will be many meditation sessions, [including] walking meditation. Soldiers go on patrol and that’s a dangerous, stressful kind of walking. [Here] they learn to walk meditatively and mindfully, trusting that a bomb won’t go off. And there will be writing, which is a meditation, and listening to one another. We build a community, which brings people out of their isolation.

To be in battle is chaos; the task is to find meaning even in that. One way is to look at its history. What social and political situations led up to this? Also personal history — how did I get to this spot? As you write, you find resolution and reconciliation.

How do you encourage scarred individuals to find words for experiences that they feel are indescribable?

One prompt has been to give people the Buddhist precepts. The first one is “Thou shalt not kill.” Everyone responds to that, because we all have killed, whether an animal in order to eat it . . . all the way up to situations in war.

Trying to heal is a long process. When I teach veterans, I use The Odyssey as a model. Odysseus goes to war. It takes him twenty years to come back. And as he’s coming back, he’s telling his story over and over again — and even when he comes back, he’s still fighting everybody.

How do you remain resolute in promoting peace, in the face of those who continue to advocate war?

I was expressing these same thoughts to one of the veterans. “Look at the Dalai Lama. He practices peace, and look at the cost. He’s lost his country. So many Tibetans are tortured and killed, and the Chinese are still in there.” And this veteran looked at me in surprise, and said, “You know, the story is not over.”

And I thought, whoa, I get it. We hang in there, and we keep making peace.

One of the wonderful things that came out of Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace is that the authors give their royalties to charity: The Vinh Son Orphanage, the D.O.V.E. Fund, East Meets West Foundation, and Code Pink. These funds have helped build a school in Quang Tri, Vietnam. One of the authors, Sandy Scull, had built an airstrip in Quang Tri during the war. Now with his poems, he’s built a school in Quang Tri. That’s the journey back to peace and creation, on a really practical level.

Nonviolence is not like the fire department — like the bomb goes off and you go put out the fire right away. We’re looking at the long-term effects of nonviolence that can stop the war of the future. Maybe not right away, but someday. The story is not over.