Web Exclusive: Follow the first voyaging canoe in modern times on a journey across the globe.

Archie Kalepa, legendary lifeguard and waterman, thinks modern technology may be responsible for the disregard of traditional wisdom and its emphasis on “sitting, watching, and remembering.”

“For example, when we teach water skills to new students, we tell them to close their eyes and put their heads under water to listen. The sound of rocks rolling tells them there is a rocky coastline. If they hear softness, or nothing, that’s sand. Crashing [sounds] tell you there are cliffs. We do this, in training, to teach people how to understand a place that they thought they knew. This is a form of teaching: Learn to listen to find out what is out there.” He adds, “I’m not a star [celestial] navigator; I’m an ocean navigator, constantly reading the direction of the wind and the swell. When those change, there might be storm swell. You have to be able to pick up on that right away, because what you’re seeing is going to dictate what you’re going to do.”

Then Archie says, “I am going to tell you a story. When the crew was being selected to take Hōkūle‘a around the Horn of Africa, it was not a very experienced crew. We learned in a preparation meeting that we were going into harm’s way in regards to the weather. The conditions around the Horn, where oceans meet, create opposing currents and huge swells in the open ocean, and 100-foot waves. When that meeting was done and we were in the elevator, it got very quiet. Someone asked me if we were going to be okay. I said that, because the canoe was lashed together, Polynesian style, not bolted or nailed, that we would work with the ocean. We would be one with the ocean. We were, in fact, hit with a gnarly storm, but when we got into port, we saw tents being erected on the dock for the funerals of the twenty-two people who were washed off the deck of the 100-foot fishing boat that had been behind us. This showed me that what we had accomplished was due to the ability and knowledge of our ancestors. Lashing is proven. It worked a thousand years ago, when no one voyaged the way Polynesians voyaged.”

A Culture of Wisdom

On Easter weekend, April 19 and 20, The Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua, hosts its twenty-seventh annual Celebration of the Arts, a largely free immersion into Hawaiian traditions, history, arts, and more. Clifford Nae‘ole, Ritz-Carlton’s cultural advisor, says this year’s theme, Aloha i na mea kanu (Love all things planted), explores the nurturing of seeds both literal and metaphorical.

“Planting seeds” is a theme near and dear to Kala Baybayan Tanaka, an educator and cultural advocate who learned wayfaring from her father, Kālepa Baybayan, navigator-in-residence at UH–Hilo’s ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, and helped navigate the voyaging canoe Hōkūle‘a on its recent worldwide tour.

“Without the foundation of the traditional ways that my kūpuna [elders and ancestors] and dad taught me, I wouldn’t have the deep appreciation that I have for the spiritual connection that happens out there on the ocean.”

Kala will share her thoughts as a Cornerstone speaker at Celebration of the Arts. For festival activities and schedule, visit CelebrationOfTheArts.org, or call The Ritz-Carlton at 808-669-6200.

From Sea to Shore

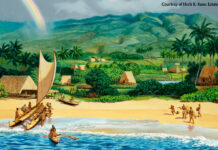

Polynesian voyagers traveled with seeds and plant cuttings, and sometimes a few pigs and chickens, in anticipation of settling new lands. They depended on the ocean to feed them as they went, and—if they were lucky—for rain to replenish their stores of water. For the ancestors of modern Hawaiians, food security would have been an immediate issue. “Sailing here was the easy part,” says Archie Kalepa. “The hard part was establishing. The ocean was the most immediately dependable resource for food”—key, early on, to survival.

Hawaiians were the first islanders in the Pacific to engineer coastal ponds for fish farming. Their design was an ingenious answer to the challenge of finding a dependable protein source. Rock walls arced out from the shore, typically enclosing a wetland or small bay where fish were known to spawn. Slatted gates allowed little fish to slip into the safety of the ponds and feed there—until they became too large to get back out. Within their walls, these nearshore “refrigerators” grew and stored mullet, milkfish and other species, to be easily harvested as needed.

“Our ancestors,” says Archie, “were way more prepared [for life] than we are today, and here’s why: Polynesians of the past were patient, observant. . . .There was no concern for time as westerners know it. But we are reacquainting ourselves with that which has been dormant for generations. Only in recent times have we come to realize that western technology cannot compare to traditional learning—seeing, touching, feeling, experiencing.”