By Rita Goldman

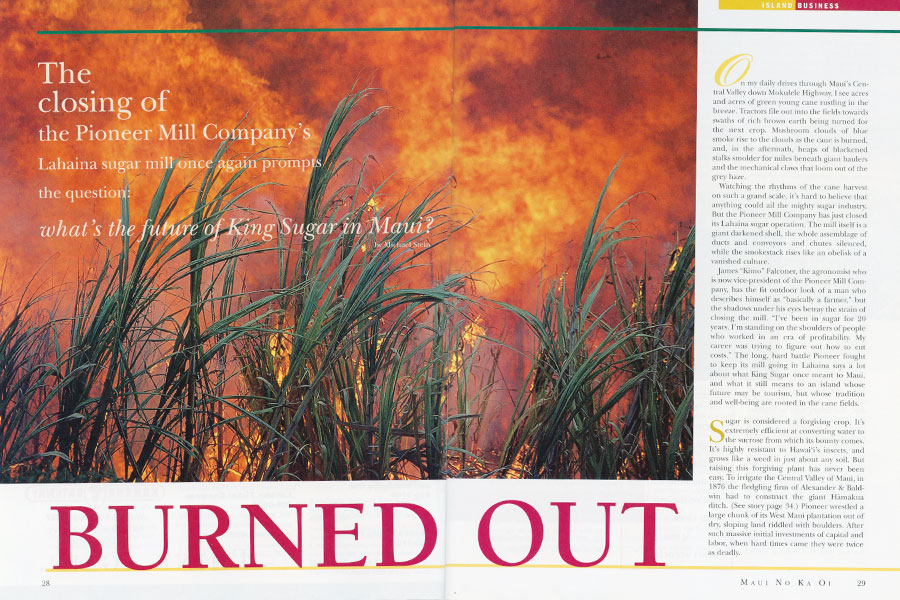

The roads through Maui’s Central Valley cross endless stretches of young, green cane. Every few months, a vast swath of those fields is burned to blackened stalks to extract the sugar, and pillars of smoke rise towards the summit of Haleakala. Giant claw derricks, spidery harvesters, and haulers the size of buildings traverse the fields in a ritual of growth, harvest, and renewal. Upcountry, pineapples blanket the hillsides, and flowers, fruit and sweet Maui onions grow on hundreds of small farms, providing thousands of Maui residents with food and livelihoods.

What if it all stops?

Michael Stein wrote those words in his story “The Growing Fields,” whose first part appeared in our Fall 2003 edition. As we pored over back issues for this, our twentieth anniversary, that story suddenly took on new relevance: Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar has announced it will cease operations by the end of 2016. The closure marks the end of a way of life — and controversy — that began here in 1823 with Maui’s first mill in Wailuku.

“The Growing Fields” was neither the first nor the last time Maui No Ka ‘Oi addressed the challenges and opportunities agriculture faces on this island. In 2000, we covered the demise of Pioneer Mill Company; and as recently as July 2014 asked, in Matthew Thayer’s “The Burning Question,” whether Hawai‘i’s last sugar plantation could survive if it stopped burning cane — a moot question now, it turns out.

In Stein’s “Water, Water . . . Where?” and Paul Wood’s 2008 “Na Wai Eha,” MNKO explored sugar’s other point of contention: the use and misuse of that most precious Maui resource, water. And in Jill Engledow’s 2007 “Power Plants?” and Stein’s later “Biofuel Battles,” we looked at some of King Sugar’s possible heirs.

As this issue goes to press, state Rep. Cynthia Thielen has proposed legalizing industrial hemp as a replacement crop for those “endless stretches of young, green cane” Central Maui will soon lose.

As this issue goes to press, state Rep. Cynthia Thielen has proposed legalizing industrial hemp as a replacement crop for those “endless stretches of young, green cane” Central Maui will soon lose.

The king is dead, long live the king? Stay tuned.