Shannon Wianecki | Photography by Jason Moore & Sara DePalma

Sheltered by lush, rain-forested cliffs in a remote corner of Haleakala National Park, Paliku cabin is a heavenly refuge. Dropping our packs, we sank into the grass. Michelle ran off in search of ‘akala, the plump Hawaiian raspberries growing wild around the cabin. The rest of us compared injuries. “Should I pop them?” Sara asked, inspecting quarter-sized blisters swelling on her feet. We all winced. Mino shook her head and offered up some duct tape. Sara downed a couple of ibuprofens and swaddled her pale, tender heels in layers of tape—backpacker’s cure-all.

Sheltered by lush, rain-forested cliffs in a remote corner of Haleakala National Park, Paliku cabin is a heavenly refuge. Dropping our packs, we sank into the grass. Michelle ran off in search of ‘akala, the plump Hawaiian raspberries growing wild around the cabin. The rest of us compared injuries. “Should I pop them?” Sara asked, inspecting quarter-sized blisters swelling on her feet. We all winced. Mino shook her head and offered up some duct tape. Sara downed a couple of ibuprofens and swaddled her pale, tender heels in layers of tape—backpacker’s cure-all.

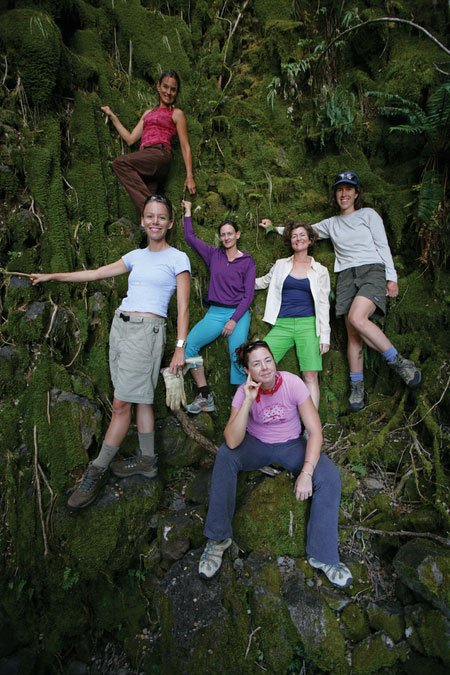

We’d expected pain. Six women (30-somethings who’d long since traded jobs as rafting guides and cruise-ship pursers for professional careers) had decided it was time to go wild, to get out of cell phone range before we became the latest version of software. We had signed up for a volunteer service trip with the Friends of Haleakala. In exchange for two nights at blissful Paliku cabin, volunteers help protect the park’s natural wonders by pulling weeds or painting fences. Matt and Farley, two directors of the volunteer organization, act as guides on the three-day trek, sharing their knowledge of Haleakala’s rare native plants and birds. The adventure culminates in an arduous descent down Kaupo Gap—seven miles of steep, rocky wilderness that even the park’s website calls “treacherous.” We had this to look forward to.

Day one took us from the 10,023-foot summit of Haleakala 10 miles down Sliding Sands Trail and across the barren, cracked lava plains to Paliku. We set out at 9 a.m. The sky was clear, the sun already blazing. Sliding Sands Trail skirts a steep, colorful bowl of cinder coughed up by East Maui’s barely dormant volcano. Volcanologists estimate that lava flows within Haleakala date from 2,000,000 to just 400 years ago. Many say it will erupt again. Incredibly, ancient Hawaiians once used Sliding Sands, or Keonehe‘ehe‘e, as a racetrack. Daredevil sportsmen flew face-forward down the slope at 70 mph, just inches above the lava, riding 12-foot-long wooden sleds. The altitude was dizzying enough for me. But unloading my pack onto a sled . . . that I’d consider.

Prior to the trip, Michelle had declared, “I’m not eating dehydrated chili for three days.” The sentiment was unanimous. Our packs bulged with three weeks’ supply of gourmet meals. Swinging from a carabiner clipped to my pack was a full-sized French coffee press. Chips and chocolate were passed around at our first rest stop, insuring that before traveling 200 steps, we gained two pounds.

We stopped regularly to snack and admire the crater’s moonscape, dotted with what looked like silver porcupines carrying bouquets on their backs: ‘ahinahina (Haleakala silverswords) in bloom. Silversword stalks, three feet tall and covered in tiny, sweet-scented blossoms, function like miniature condominiums for native insects—the only soft place to hide in this harsh, wind-blown climate.

By the time we reached Paliku, my legs felt like overstretched rubber bands. My left knee was on strike. I feigned interest in the native mistletoe along the way, so I could rest. We hadn’t even hit the rough stuff yet—would I need to be airlifted out of the Gap? Farley tried rallying the group for an evening stroll to peer over the edge of the Gap and survey the view. “A hike after our hike?” Ashley asked, looking dubious. Alas, dinner proved more inviting. Sara and Mino plied us with a sumptuous feast: fresh mozzarella and sun-dried tomato pasta. Matt earned our instant devotion by tossing a tub of homemade cookies onto the table.

As night fell, we indulged in tea and games by candlelight. During a round of “two truths and a lie” one of the men stumped us: “I don’t like girls; I don’t like bicycles; and I’m a vegetarian.” Six girls went silent. (We knew the last statement was true; which was the lie. . . ?) Michelle brought out two rubber-spiked thingies for the sole purpose of stretching them over her head to make us laugh. Mino pulled on pink Polartec pajamas, and I donned my prairie-style sleep cap. In the wilderness, luxuries like these are essential.

As a flask of whiskey made its way around, our laughter mingled with the eerie chirps and calls of ‘ua‘u (native petrels) darting into rock burrows outside. Without the ambient glow of city lights, the stars were clear laser points. Scorpio, known to the Hawaiians as Manaiakalani, or Maui’s fishhook, shone high and bright in the sky. Many centuries ago, Hawaiians found their way to these islands following Manaiakalani and other constellations. Eons before that, by the same stars, the ‘ua‘u traveled here, as they did tonight.

The Crystal Cave

On the way back to camp, we detoured to Crystal Cave, a lava tube created by trapped volcanic gasses. (Off-trail spots like this, I should mention, are only accessible to Friends volunteers.) Ducking out of the relentless sun, we found soft green ferns and mosses thriving beneath the rock outcropping. Our flashlight beams lit up white and yellow crystals sparkling on the interior walls. Caves like this are home to some of Hawai‘i’s most romantic insects: native cave crickets. Blind and colorless, the crickets compose complex songs to attract one another through underground cracks and fissures. I strained to hear them before heading back into the sun.

Later that night, Sara pulled a hidden bottle of port from her pack—a sweet indulgence courtesy of some very sore feet.

The Gap

Day broke; the time had come to conquer the Gap. Leaving Paliku behind, we passed through a moss-covered gulch. I heard a distinctive trill. A plump yellow bird with a telltale brown mask toyed in the branches above—was it Maui’s rare, endemic parrotbill? I didn’t get a close enough look to be certain, but the mere possibility of having spied one of 500 remaining birds felt like a good omen.

Kaupo Gap is legendary, and not just for claiming victims. From the top of the trail, the tangled blossoms and sickle-shaped leaves of native forest tumbled down as far as the eye could see. Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, the Big Isle’s tallest peaks, broke through the clouds on the horizon. A true wonderland opened up before us. In every direction koa, ‘ohia, mamane, and a‘ali‘i grew on top of one another. Accustomed to seeing these plants in isolated pockets, I was overwhelmed by their abundance. On an island where much of the native flora and fauna verges on extinction, this rare view defied comprehension.

We passed strange hybrids as we traveled down the switchbacks. Kupa‘oa, one of the more plastic members of the silversword family, mingles pollen with other species, creating spontaneous new hybrids in the process. Many have yet to be scientifically described; Farley joked that we could each name one. We ate lunch in an enchanted forest glade. Beneath wide-armed koa trees we shared the last of our food. (It’s true!) Michelle twisted maile vines into a crown. Matt and Farley disappeared in search of yet another rare bloom. I turned somersaults in grass so thick and soft it might’ve been hallucinogenic. We discussed setting up camp here and permanently turning our backs on trivialities like Netflix and running water.

Reluctantly we continued on and found ourselves at “Koa Trees,” the park boundary. Until now, the trail hadn’t been so treacherous. A final exuberant burst of native forest clamored up to the fence, where Kaupo Ranch’s comparatively bleak-looking pasture took over. Beyond lay the terrain we’d been warned about: a steep descent of ankle-breaking boulders. No hint of shade. The sun’s rays strengthened. Farley ambled along easily; this was a stroll home for him. I pulled myself along with the aid of walking sticks—no easy task for a beginner; it’s rather like learning to crawl on stilts. The last two miles were truly terrible. Each of our aches began to throb, then scream. But we were so close! We could almost see the truck waiting for us, with its promise of ice-cold beverages. In delirium, we danced jigs and dodged cow pies.

When we hit the road, we tallied the weekend’s sacrifices: Michelle lost two toenails; my left knee was burnt crimson. Sara’s blisters would take three weeks to heal. And in the last mile, a loud pop came from poor Matt’s ankle. Was the pain worth the gain? Definitely. During our three days without electricity, we unwound. We saw the ancient, untouched side of our island and, perhaps, glimpsed a little of the same in ourselves. On the drive home, we were already planning our next excuse to go wild.