Story by Kathy Collins

Having grown up here in the 1950s and ’60s, I sometimes—okay, often—wax nostalgic about the Maui of my youth, when the resident population was a quarter of today’s, folks waited patiently on two lane roads for drivers headed in opposite directions to finish chatting, and TV shows arrived by plane a week after airing on the mainland. Time has brought many changes, but vestiges of that sweeter, simpler Maui remain, among them several venerable buildings that have been preserved, restored and brilliantly repurposed. These grand old dames brimming with new life comfort and inspire me. As an aging structure myself, I’m grateful for the thought that good maintenance and a fresh mission could extend and enhance my golden years, too!

NATIONAL DOLLAR STORE

When the San Francisco-based National Dollar Stores chain opened its Maui outlet in November 1951, thousands of eager bargain hunters flocked to Wailuku for the grand opening. A little farther up Main Street, S. H. Kress Store had already established itself, sixteen years earlier, as the premier shopping destination for islanders. The National Dollar Store was a little smaller than Kress, and it didn’t have a lunch counter or sticky-sweet colored popcorn, but its main attraction was budget clothing for the entire family, no matter how large your family or how small your budget. The store also featured housewares and toys, lots of toys, again at discount prices.

Several generations of local families ritually made pilgrimages to National Dollar for back-to-school wardrobes and holiday gifts. While Mom pored over racks and stacks of garments, we kids gleefully rummaged through giant bins of plastic toys: cars, dinosaurs, little green army men. Even Dad could get into shopping mode, browsing through sporting goods, hobby equipment, or household gadgets.

The retail chain folded in 1996 after nearly a century in business on the West Coast and in Hawai‘i. The following year, with a county grant and a low-interest federal loan, the Maui Academy of Performing Arts bought the empty Wailuku store and converted it into studios and workspace. Today, more than 2,000 children and adults annually attend classes in dance, drama, and singing at the MAPA Main Studios. The building again buzzes with the joyful energy of youth; only now, instead of squeals of delight over discoveries in the toy bins, visitors hear the laughter and cheers of children finding themselves.

BAILEY HOUSE

My first childhood home, tucked between mango and avocado trees on a narrow Wailuku lane, sat about a quarter mile from the Bailey House. One 1960s summer, my cousin and I pedaled up the hill on our tricycles to check out the then-new museum. The kindly tūtū (grandmother) at the reception desk gave us free rein, and after a few daily visits, we became unofficial docents, greeting the tour buses on their way to ‘Īao Needle. A few times, we strung lei of plumeria from my cousin’s tree and sold them to visitors for fifty cents each. For another dollar, we’d give them a guided tour of the old missionary home, which, by then, we considered our own.

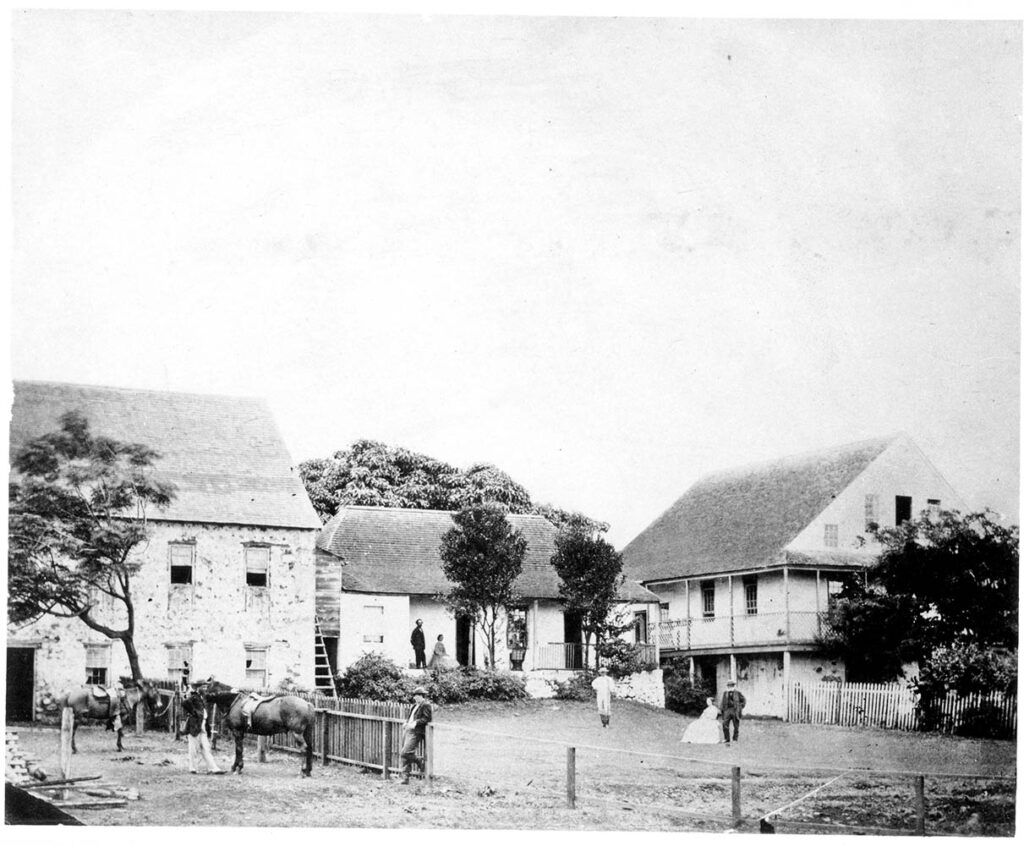

The historic significance of the Bailey House, originally named the Central Wailuku Female Seminary, predates the building itself. Constructed in 1833, the old mission school stands on the grounds of what was once the royal compound of Kahekili, Maui’s last ruling chief. Missionary Edward T. Bailey served as headmaster from 1840 until its closure in the mid-1850s. A man of far-ranging talents, including oil painting, engineering, botany, and poetry, Bailey designed the nearby Ka‘ahumanu Church, as well as numerous roads and bridges in the area. He built and operated his own sugar mill on the site, and became the first manager of Wailuku Sugar Company. After Bailey and his family returned to the United States in 1888, the home continued as the plantation manager’s residence until 1924.

Over the next several decades, the two-story stone structure housed Wailuku Sugar’s offices, and was used as Civil Defense headquarters during World War II. In 1957, the plantation offered the newly formed Maui Historical Society a $1 annual lease of the building and grounds for a museum named Hale Hō‘ike‘ike (House of Display). When the plantation closed in 1992, Maui businessman and philanthropist Masaru “Pundy” Yokouchi purchased the property, then donated it to the society.

As Maui’s nascent tourism industry took root, the museum’s board dropped the Hawaiian name, perhaps because “Bailey House” was easier for visitors to pronounce—and remember. With the resurgence of Hawaiian culture, the museum’s original name has been brought back. Today Hale Hō‘ike‘ike at the Bailey House holds Maui’s largest display of Hawaiian artifacts dating back to the pre-contact era. Where young Hawaiians of an earlier century were once taught “proper” western skills, the society now presents historical lectures and workshops. The museum’s gift shop offers a variety of made-on-Maui products (though no longer by six-year-old lei makers); and extensive archives, stored in a downstairs vault, are accessible to the public by appointment. “We are the caretakers of Maui’s history,” says Hale Hō‘ike‘ike executive director Sissy Lake-Farm.

KAUNOA ENGLISH STANDARD SCHOOL

Even after being recognized as a legitimate creole language, our island “Pidgin” is still mistaken for a local dialect or “broken English” by both newcomers and kama‘āina (native-born; literally, “child of the land”). Hawai‘i Creole English evolved on the islands’ nineteenth century sugar plantations as a way for immigrant workers from Asia and Europe to communicate with each other and with their English speaking bosses. HCE/Pidgin eventually became the primary tongue for generations of locals.

In 1920, fearful that their children could not receive adequate education in public school, where Pidgin was the first language of most students, 400 Caucasian parents petitioned the territory’s Department of Public Instruction for a school in which only “proper” English would be spoken. That same year, a federal study concluded that the prevalence of nonnative English speakers in the public schools was indeed a detriment. Four years later, the department initiated the English Standard School system at Lincoln Elementary on O‘ahu, and in 1926, the Maui Standard School (later renamed Kaunoa English Standard School) opened in Spreckelsville, a thriving company town at the time.

Though many folks referred to it as “the haole [foreign] school,” attendance was not based on ethnicity; however, to be accepted, a child had to pass an English fluency test. The first few classes were predominantly Caucasian, because haoles were the only ones who spoke Standard English at home, but gradually Kaunoa’s population included students of various ethnicities. Most grew up bilingual, comfortable with Standard English as well as HCE. The late U.S. Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink and former Maui Mayor Charmaine Tavares were Kaunoa graduates; either one could turn on the Pidgin “mo’ fast than one ‘uku [flea] can jump!”

Controversial from the start because of its inherent segregation, the English Standard system fell further out of favor after World War II, and in 1949, the state legislature ordered the DPI to begin dismantling the system. Kaunoa was converted into a regular public school in 1957. In 1964, dwindling enrollment forced its closure.

But not for long. With the federal Older Americans Act of 1965, Kaunoa School became a multipurpose center for senior citizens, operated by the community organization Maui Economic Opportunity. The County of Maui took over in the early 1970s, and Kaunoa Senior Center now serves more than 5,000 participants annually through its services and programs, including home-delivered and on-site meals, assisted transportation, volunteer opportunities and recreational activities. Kaunoa offers over 100 classes each week, from acrylic painting to Zumba.

Outside the old cafeteria—the one original building that remains, though its shell has been refurbished—a memorial plaque sits beneath a sprawling monkeypod tree, which, presumably, is also an original school fixture. Donated by the Class of 1957 during its fiftieth-anniversary reunion, the plaque often spurs fond recollections by Kaunoa School alumni who are now Kaunoa Senior Center volunteers and participants. More often than not, those memories are recounted in Pidgin. Just sayin’.

LAHAINA COURTHOUSE

In the 1960s, the state Department of Education designated fifth grade to be the year of “Hawaiiana,” when all public-school children would study the history of our islands. For Maui kids, the highlight of fifth grade was the requisite excursion to Lāhaina for a tour of the former capital’s historic sites: the coral-walled prison yard of Hale Pa‘ahao (Stuck-in-Irons House), Hawai‘i’s first printing press at Lāhainaluna High School, and my favorite stop: brown-bag lunching under the banyan tree before exploring the adjacent courthouse.

Built during the reign of King Kamehameha IV, the original Lahaina Courthouse opened in 1860 with a single courtroom, offices for the governor of Maui, sheriff and district attorney, a post office, and a customs house for whaling and trade ships. After the U.S. annexation of Hawai‘i in 1898, the building continued to serve as a government center, but the American flag replaced the banner of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. In 1925, the courthouse was renovated in the Greek architectural style with a gabled roof, a balcony overlooking Lahaina Harbor, and stately columns guarding the entrance. The courtroom remained upstairs, the post office and police station occupied the ground floor, and a jail was installed in the basement.

In the 1970s, those functions were relocated to the new Lahaina Civic Center on Honoapi‘ilani Highway near Kā‘anapali. And when the law moved out, history and the arts moved in. The old courthouse is now home to the Lāhaina Visitor Center, Lāhaina Arts Society galleries, and the Lāhaina Town Action Committee offices. On the second floor, alongside the preserved remnants of the original courtroom and the Hawaiian flag that was lowered in 1898, the Lāhaina Restoration Foundation has installed the Lāhaina Heritage Museum in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation.

History buffs and ocean enthusiasts will find much to explore here, from the museum’s extensive displays and artifacts, to a small movie theater with archival films on a loop. Downstairs, behind the bars of the old jail cells, paintings and photographs by Maui artists provide a decidedly more pleasant atmosphere than experienced by the rowdy revelers and errant sailors of old.

HALI‘IMAILE GENERAL STORE

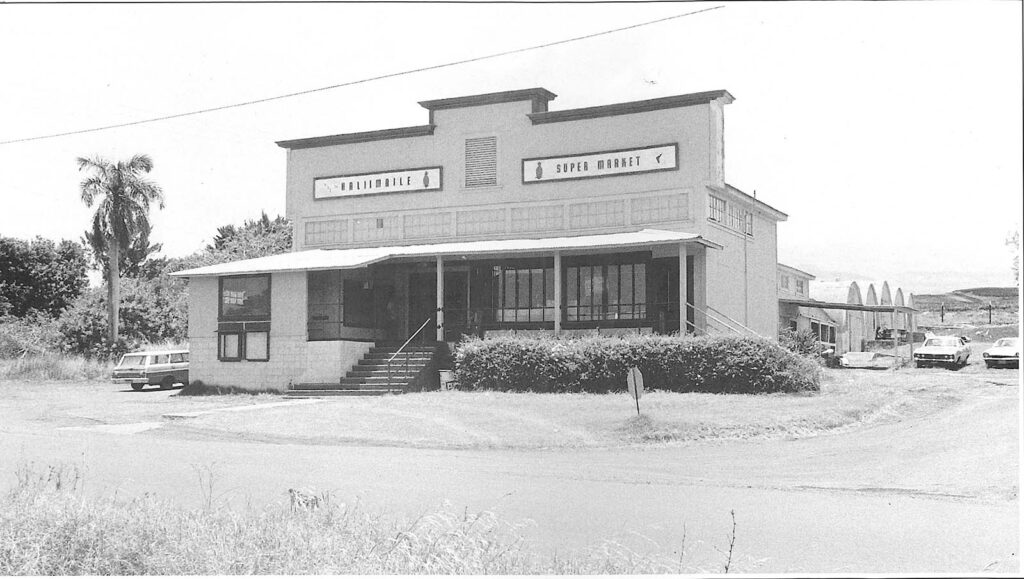

For more than thirty years, this Upcountry restaurant has earned the acclaim of gourmets and gourmands with its award-winning American/Asian cuisine. But kama‘āina of a certain age fondly remember when its most popular culinary offerings were Saloon Pilot crackers and canned Vienna sausages.

Back then it really was a general store, built in 1925 by Maui Agricultural Company, the forerunner of Maui Land & Pineapple Company, to serve what was then a pineapple plantation camp. Throughout the golden era of “King Pine”—up until the 1970s—Hāli‘imaile Store was a one-stop shop for plantation families, and a virtual village square. After a long day in the fields, workers would stop by to check their post office boxes at the front of the store and linger on the large lānai to “talk story.” Housewives visited the butcher shop, fish market, or grocery department daily, in preparation for the evening’s meal. As second-graders, my best friend and I raced to the store from the camp bus stop every Friday afternoon to buy penny candy and vanilla Popsicles for the walk home.

When she took over the building’s lease in 1988, Bev Gannon was still a few years away from being recognized as one of the twelve island chefs who defined Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. She intended to run a gourmet deli and catering service along with the general store, but before long, Gannon acquiesced to her patrons’ requests for a sitdown restaurant . . . and the rest, as they say, is history.