Story by Judy Edwards

The humpback whale calf swam in circles on the ocean’s surface just off the coast of Lāna‘i. A monofilament line was wrapped tightly around her, digging deeply into her flesh and blubber, a potentially lethal belt. Calves grow rapidly, and bindings such as these can disappear into their skin over the course of just a few days. Her mother hovered about 50 feet below the surface between breaths, sunbeams shafting through the cobalt water. The calf dove frequently to join Mom, but, lacking Mom’s lung capacity, she could not stay down long and would pop to back up to breathe every few minutes.

In a boat nearby, Ed Lyman waited with his team. Lyman is the regional coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s large-whale entanglement response. He and his team had received a call from a whalewatching boat that had discovered the entangled calf and had stayed with mother and baby until the NOAA rescue crew arrived.

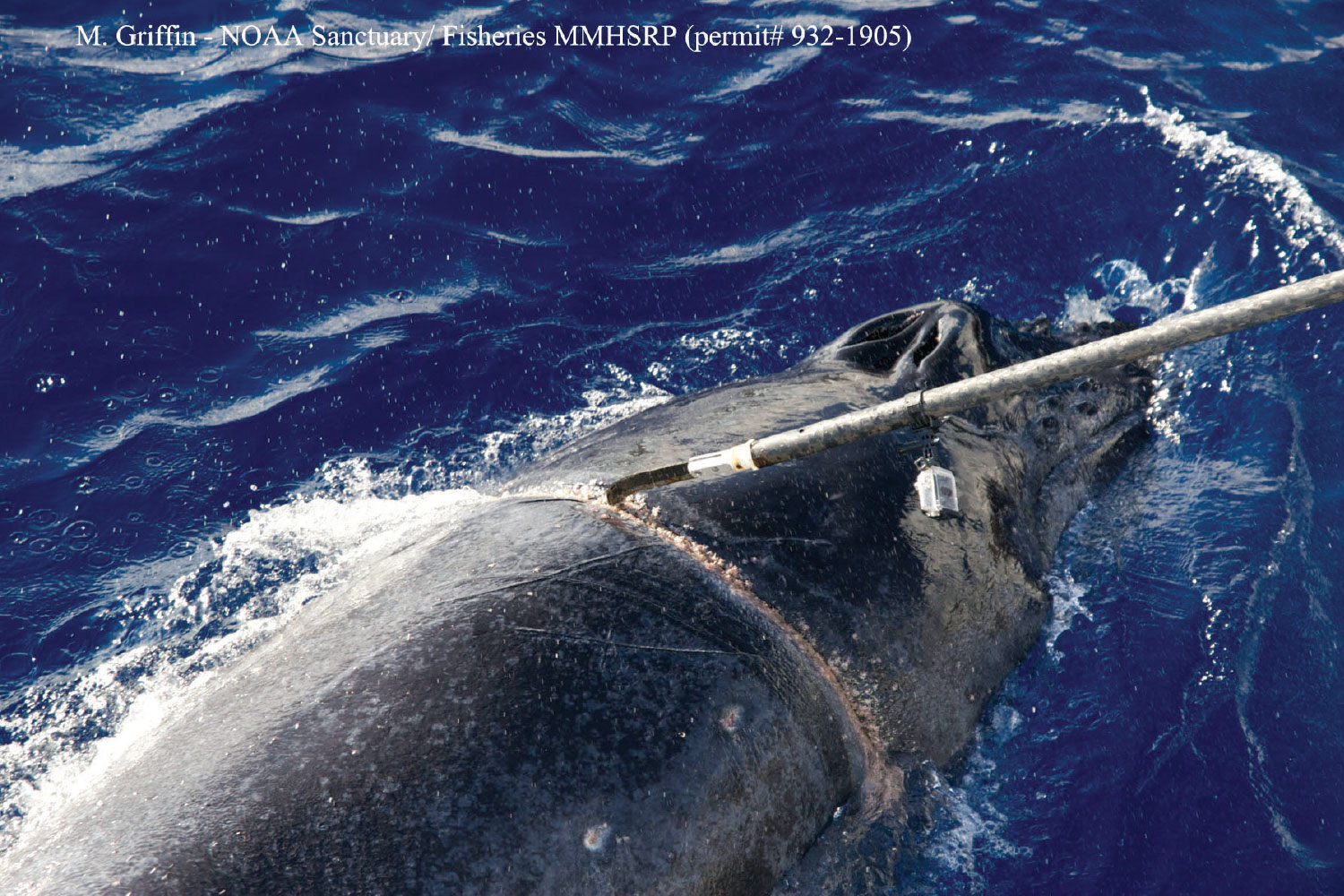

On one of her surface laps, the curious calf deviated a bit toward the boat. Lyman reached for a long pole topped with a Thompson blade, a specially designed knife created on Maui, to try to cut the embedded line. At any minute, Mom might rise and herd her calf away from humans and boats.

Lyman gauged the distance, hefted the pole and reached across the water for the cut.

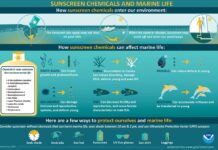

From early November to mid-May, the waters around Maui slowly fill with humpback whales. They arrive for the breeding and calving half of their yearly migratory cycle, traveling from the food-rich northern waters bordering Alaska and the Arctic, dodging threats along the way such as hungry orcas and oil spills, as well as floating, abandoned fishing nets and gear, and all manner of lines. This detritus can become entangled with buoys, homemade FADs (fish aggregating devices) and other random flotsam and hang down into the water column.

“The [fishing] gear is stronger than it used to be,” says Lyman. “We went from natural fibers to polyester blends with a very high breaking strength and which don’t degrade in the sun and sea salt very fast. Whales can learn, but we keep throwing changes at them … and that really impacts the youngsters who are just figuring things out.” Such curiosity can be fatal, and whales can starve or even drown when entanglement restricts their movement. Then there’s the inexorable, unfolding juggernaut of chaos that is climate change.

“Climate change moves the feeding grounds around, so the whales [have to] move to find food,” says Lyman. “These new waters are unfamiliar … and may increase their entanglement risk.”

In the enormity of the ocean, just trying to locate a humpback in trouble is a monumental challenge. But despite the odds, Lyman and his team have successfully disentangled more than 30 humpbacks of all ages, and this, thanks in no small part to the assistance of the community.

“We don’t usually find these whales on our own, and can’t dedicate the time to search for them,” Lyman says. “But our community — the whale-watchers, tour-boat operators, fishermen, pleasure boaters — anyone on the water can be an ‘opportunistic’ first responder, [and spot and report] an entangled animal. [Tours that] spot an entangled humpback and stay with it will have the whale watch of their lives, and everyone gets to be part of a rescue.”

When a call comes in to the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, Lyman and team hustle into action. The highly trained crew consists of biologists, fishermen and professional mariners, each of whom brings an associated skill set to the mission. They collect their equipment — including an inflatable boat, buoys, grapples, carbon-fiber poles and safety gear — then hurry to their boat, the Koholā, and set out to locate the imperiled whale.

Disentangling a 45-ton animal is dangerous, and the first goal is to attach buoys to any trailing entangled lines. This helps slow the whale down, tire it out and keep it on the surface, making a safer rescue approach more probable. The whale, of course, has no idea that the team is there to help, and may defend itself with its massive tail, try to dive, or suddenly pick up speed, hauling the would-be rescuers along. The process may take several hours — or even days — and if nightfall or the weather doesn’t force the team back to the harbor, and the whale stays calm enough to work with, the disentanglement can proceed.

The team deploys hooks and blades attached to long poles to catch and cut away lines and netting. “Some lines become so deeply wrapped [around a whale] that our regular knives can’t get to them,” says Lyman. “The season before, we lost an entangled calf because we didn’t have the right tool. We needed a way to cut into the [whale’s flesh] to save it.”

Enter the aforementioned Thompson blade, which was invented by one of Lyman’s team members, Grant Thompson. Thompson bought a knife with a large, curved blade traditionally used for cutting bamboo and modified it so both the inside and outside edges were sharp. He attached it to the end of a pole which was long enough to reach from the rescue boat over the water to the whale’s body in order to cut away the lines. His innovative blade has been so successful that it is now used by detanglement teams around the world.

Once a whale is successfully freed, the team gathers all the cut lines, cables, nets and other garbage in order to determine their origins and makeup. Knowing what kind of gear poses the greatest entanglement threat and where it’s coming from are the first steps to getting out in front of the problem.

Despite the humanitarian desire to help, Lyman urges citizens not to attempt a rescue on their own. “They might get some of the trailing lines off, but the tight wraps may remain, cutting into the whale,” says Lyman. “Now the trailing gear, which we could have used to spot [the whale] again, is gone, and it’s a dead whale swimming.”

As for the photos and videos of well-meant but unprepared and unauthorized disentanglements posted on social media, take those with a grain of salt. “In many cases, people get hurt, but those attempts never get posted,” says Lyman. “People don’t realize going in how the risks are stacked against them.”

Reporting a whale in danger to an experienced rescue team is the best thing folks can do. Take photos and monitor the whale, staying by it if you can, or trade off with other boats in shifts so the animal doesn’t get lost. “If people can safely stand by after the call, and I can ready the boat and gather the team, we have a chance,” says Lyman. If all runs smoothly, Lyman and his team can make it to most disentanglement situations in about two hours.

All the pieces aligned the day Lyman was faced with that calf.

“I landed the Thompson blade in the indentation of the rope, caught it and cut it,” says Lyman. “The rope was so tight that it exploded off of her.”

Once her calf was freed, Mom surfaced and the two swam slowly away. “The whale-watch boats launching from Lahaina saw the pair for at least a month afterward,” says Lyman. “The calf was very playful and fun to watch, and they could clearly see the scar around her middle where the line had been. They named her Hula Hoop.”

How to help

To report an entangled whale, call the NOAA Fisheries Hotline at 888.256.9840 or hail the U.S. Coast Guard on VHF channel 16.

Maui residents interested in further training can take the US Whale Entanglement Response Level 1 course. This teaches citizens to properly assess, document and report critical entanglement to authorized and highly trained rescue teams. Go to pacific-islands-training.whaledisentanglement.org/#/ for more information.

Disentanglement authorization falls under the oversight of NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources’ Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program. Their efforts to free a large whale are permitted to reduce the risks to both animals and people.