Shannon Wianecki

Daydreaming about taking a scuba dive or kayak tour of Maui’s rugged southern coast? Better check if it’s permitted, first. The island’s idyllic shoreline has recently become the stage of a tug-of-war between ocean-activity operators and Maui County regulating forces.

Daydreaming about taking a scuba dive or kayak tour of Maui’s rugged southern coast? Better check if it’s permitted, first. The island’s idyllic shoreline has recently become the stage of a tug-of-war between ocean-activity operators and Maui County regulating forces.

Complaints that county beach parks are overcrowded and that unregulated businesses are benefiting at the public’s expense spurred Parks and Recreation officials to revise the rules governing commercial ocean-recreation activity (CORA). When the County released the proposed new rules last August, local business owners panicked.

Currently, fifty companies hold permits to offer surfing, windsurfing, kiteboarding, scuba diving, snorkeling, or kayaking excursions at twenty-two beaches islandwide. The proposed new ordinance would have limited the number of CORA permits issued, nullified the transfer of permits, specified limited hours during which commercial activity is allowed, required the use of shuttles to alleviate parking congestion at some beaches, and eliminated several beaches formerly open to commercial use.

Fearing these strict new regulations would drive them out of business, several CORA operators wrote letters to The Maui News and petitioned lawmakers to reconsider. In response, County officials placed a moratorium on new CORA permits, and extended current permits until the new rules could be hammered out. Months have passed, numerous public meetings have been held, several revised drafts of the rules have been circulated, and there’s still no consensus on exactly how to manage commercial business at county beach parks.

At a Kihei Community Association meeting in April, activity operators sat down with concerned community members to brainstorm solutions. It was a chance for stakeholders to discuss problems face to face. While County representatives declined to attend, suggestions made throughout the evening were compiled and submitted to the Parks Department.

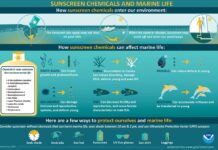

Local resident Michael Duberstein was among those at the Kihei meeting with concerns about commercial traffic’s effect on the natural resources.

“I don’t know the answer, but some sort of understanding has to be reached with these commercial operators who say they’re doing everything to protect the reefs,” says Duberstein. “It’s a little hard to just go on their word. We know the coral reefs are suffering. Every study that’s been done on reefs shows that they’re in desperate condition.”

While concerns about marine impacts are valid, they don’t fall directly under the purview of the County ordinance. County jurisdiction ends at the high-water mark, where the state Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) takes over. The County’s focus is on land, where commercial vans and buses monopolize parking, and equipment such as dive tanks and kayaks take up precious real estate on beach walkways.

“Complaints from the general public regarding the overcrowding of beach parks, the lack of adequate parking, the need for upgraded restroom facilities, better shower drainage, more picnic tables, more barbecues, and less people to scare fish away are made many times a week to our staff,” says Parks and Recreation Director Tamara Horcajo. “These are usually anonymous and come out of frustration from individuals or families who want quiet time at the beach park.”

Ironically, CORA operators have voiced some of the loudest complaints to the County, petitioning officials to regulate the renegade, fly-by-night operations that give the industry a bad name.

“There are some very good and solidly built ordinances that aren’t being enforced,” says Kiteboarding School of Maui owner Martin Kirk. “The rules say you can’t have a van at the beach. Right now we have guys on the beach who don’t have a permit, who don’t have insurance. They’re renting equipment out of their cars. I’m operating at a huge economic disadvantage because they get all the walk-in traffic.” Kirk went as far as hiring an attorney to convince the County to enforce its own rules—to no avail. “All I want is the County to be consistent—either enforce the rules or eliminate them. Right now I follow the rules and I can’t be competitive.”

Thanks to the recent hiring of four park rangers, enforcement is likely to be more consistent in the future. But that only partly answers Kirk’s worries.

“My concern is that the current parks director really has an agenda: to literally drive us out of business, which would allow the County to put the parks up for bid. That was one of the first things she told me after taking office.”

Horcajo maintains that isn’t the case. “Concession agreements, where companies bid for the business, are something we could look at in the future. It isn’t what we’re looking at so far.”

Responding to criticism that the regulating process has been antagonistic to the industry, Horcajo says, “I have felt it and I’m really sorry. We know that the services are wanted. But more people are here now. We don’t have a lot of beaches, we aren’t getting new facilities, and the parking is maxed out. The time has come. We have to draw the line.”

Many CORA operators feel that the line is being drawn too close to their livelihoods and that they are being targeted as scapegoats for a variety of problems. It’s not activity companies’ fault that there are too few beach barbecues and parking stalls. To the list of complaints lodged against them, CORA operators add their own grievances, directed at the County.

“I don’t think it’s fair to say that overcrowding is due to commercial operators,” says Jeff Strahn, the manager of Maui Dive Shop. He’s been working on CORA issues with the County through several administrations. “They are a part, for sure. But not one new beach park has been built since 1955, no parking stalls developed, while our population has grown.”

Horcajo also recognizes the lack of park development as a serious problem. “We have not had funding for new parks in ten years,” says the exasperated director. “We need more space, more parking lots, more bathrooms . . . we need more everything!

“Our community has grown so fast, parks have not kept pace with the needs,” says Horcajo. “In terms of park requirements, we’re far below the national standard. My perspective is that the needs for our infrastructure—water, roads, sewers—have taken precedence. Parks do continually get put on the back burner.”

Parks are funded in part by fees levied on new construction projects. Horcajo explains that, in the past, the fees weren’t high enough to pay for new parks.

“Previously, the assessed fees were very small, and that was at a time when Maui was booming. When the administration caught up, and realized park needs weren’t being met, the amount of development had gone down. Those big developments you see were passed years ago under the old fees.”

Charlie Jencks, past Public Works director and the developer behind the Wailea 670 subdivision, says he’s required to pay $17,000 in park fees per unit—that’s under the new fee structure. Unfortunately for beachgoers, that chunk of change is already earmarked for a long-stalled terrestrial project: the South Maui Park below Pi‘ilani Highway. No new beach parks are in the works.

“We’re trying really hard to figure out how to increase the capacity at our existing shoreline spaces,” says Horcajo. “As far as purchasing oceanfront property from current landowners, that isn’t really feasible.” Real estate, she says, has simply grown too expensive. “So the concept of privately owned, privately maintained parks is something we need to look at. Makena, for instance, is a really good resource for the community.”

The three beach parks in Makena—Makena Landing, North Malu‘aka and South Malu‘aka—are open to public use, but the restrooms and other facilities are owned and maintained by the neighboring resort. The same holds true of other sites around the island, including D.T. Fleming Beach Park in Kapalua. This public-private arrangement serves some in the community, but it doesn’t allow for outside commercial use. When Makena Resort changed ownership recently, the issue was brought to the attention of the new owners. The three aforementioned Makena beaches—including one of the island’s best kayak launching spots—were added to list of parks where commercial activity is banned.

“We’re like the unwanted child,” he jokes grimly. “We keep getting pushed from place to place.”

South Pacific Kayaks owner Roger Simonot is one of several operators whose permit to launch tours from Makena Landing expired September first. “There is no better place for kayakers,” says Simonot. “We’ve been down there over twenty years. We’ve been permitted all these years; we’re doing everything the County has asked us. It’s pretty discouraging that the County is not stepping up to the plate. If they’re going to permit us, back us up.

“We’re like the unwanted child,” he jokes grimly. “We keep getting pushed from place to place.” He relates how, when ‘Ahihi Kinau Natural Area Reserve was closed to commercial use in 2004, resource managers predicted greater traffic at Makena Landing. Now that Makena is closed, the only south-shore site open to kayak companies is Kalama Beach Park. “If they’re concerned about overcrowding, moving us around won’t address those complaints.”

One possibility under discussion is opening “Chang’s Beach,” or Po‘olenalena, to commercial use. It’s closed under the current rules, as it lacks suitable restroom and parking facilities, but Horcajo says it’s being assessed for future use. In the meantime, kayak operators must choose between launching at busy Kalama Beach Park, where the conditions aren’t as appealing, or forgoing tours on the south side of the island altogether. “We don’t know what we are going to do,” says Simonot. “It’s a day-by-day thing.”

What does the community stand to lose if activity operators are pushed out? According to a 2005–2006 County study, the ocean activity industry makes substantial contributions to Maui’s tourism economy. CORA permit holders provide “greater security, and to some extent safety, for visitors and residents who patronize these businesses.” Permit holders are required to have current emergency first aid training and equipment, which can mean the difference between life and death for beachgoers in remote areas. CORA operators are also required to carry liability insurance, shielding the County from lawsuits.

Commercial operators point to other benefits, saying they fill important gaps that the County doesn’t address. Maui Surfer Girls, for instance, offers surf-camp scholarships to the Boys and Girls Club of Maui. Octopus Reef owner Rene Umberger sponsors regular reef cleanups with Maui Reef Fund and Project Aware. Partnering with other dive companies, she’s hauled more than 2,000 pounds of abandoned fishing gear off island reefs over the past three years. Don and Rachel Domingo, of Maui Dreams Dive Company, received a Living Reef award in 2007 for their volunteer work monitoring and repairing underwater moorings. They dispute the perception that activity companies serve tourists at the expense of the local community; more than 50 percent of Maui Dreams clients are local residents.

“The partnership with the CORA businesses needs to have a balance so that our limited resources are available for all recreational users,” says Horcajo. “If we can get these administrative rules in place, it will be a really good study to see how they work. We can always change them. We’ve got to start somewhere.”

Maui Dive Shop’s Jeff Strahn, along with many other operators, has provided information that the County used to revise the rules first proposed in August, and now in their third draft. While previous versions would have “caused the industry to collapse,” Strahn says the version on the table right now “addresses the County’s concerns” and is “a good compromise.”

“Mayor Tavares has been very supportive of [having] our department work with the existing operators and take the time for these many draft revisions,” says Horcajo. “I believe we have found a good balance between strictly public use and commercial operation with this draft.”

Meanwhile, at the state level, DLNR chairwoman Laura Thielen is acting to enforce additional rules, saying, “If you’re standing in sand, it’s probably state land and you need a permit.”

“That’s coming down the pike,” says Strahn, who’s resigned himself to never-ending negotiations to keep his livelihood legal. “That’s a different battle for a different day.”