Kathryn Wilder | Photography by Jason Moore

Before I enter the Wailuku studio I am met with smells reminiscent of my grandfather: turpentine and oil paint. All that’s missing is the smoke of Camel cigarettes and the physical incarnation. When I step into the large, clean room, at first I think I am alone, but soon find myself among spirits seen and unseen. Even the paintings of ti have spirit—light and color and energy. Later I will learn that painter Philip Sabado and his wife, Christine, were around the corner in their air-conditioned office, but for the moment I enjoy the quiet company of my long-passed grandfather and the kupuna (elders) who inspire Philip’s work.

Before I enter the Wailuku studio I am met with smells reminiscent of my grandfather: turpentine and oil paint. All that’s missing is the smoke of Camel cigarettes and the physical incarnation. When I step into the large, clean room, at first I think I am alone, but soon find myself among spirits seen and unseen. Even the paintings of ti have spirit—light and color and energy. Later I will learn that painter Philip Sabado and his wife, Christine, were around the corner in their air-conditioned office, but for the moment I enjoy the quiet company of my long-passed grandfather and the kupuna (elders) who inspire Philip’s work.

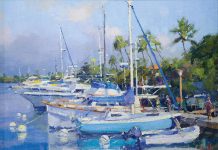

Red ti, green ti, taro. A mallard swimming in a lo‘i (taro patch); a boy in an outrigger fishing canoe; honu, Hawai‘i’s green sea turtle, in the blue-green water. In one painting a double-hulled canoe approaches, the royalty on board draped in yellow-feathered capes, the line of red down the middle of their helmets striking in the light. Three additional ali‘i await their arrival on land. I do, too, before moving slowly on to a huge canvas standing sentinel in the corner. A canoe sits in the foreground; behind, spanning over a quarter of the canvas, a face emerges. I exit the studio quietly, holding canvas visions in my heart, happy to have had this private viewing.

The next time I visit, the studio bustles with activity as Philip’s students, many of them from Kaunoa Senior Center, put finishing touches on their day’s work and clean up. My mother, daughter of my grandfather the painter, has joined me. Christine Sabado, Philip’s wife of 37 years, ushers us into the office I didn’t see before; our eyes wander the walls, experiencing layers of color and story as we absorb the rich oil paintings of old Hawai‘i.

Philip joins us, speaking modestly of his impressive education. The son of parents who emigrated from the Philippines in the 1930s, Philip was born and raised on Moloka‘i. After serving in the Army, he pursued a career in art. He met Christine at the Honolulu Academy of Art; eventually they moved to Los Angeles, where Philip continued his education at the Art Center in Pasadena, Otis College of Art and Design, and the Columbia School of Design in Paris.

Eight years later, Philip was well on his way to a successful career in commercial art and had been offered a promotion to art director in an esteemed New York firm. He and Christine were contemplating the move when they took a little trip to Las Vegas, where Philip ran into an old friend whose daughter was performing at a ho‘olaule‘a (celebration). As Philip watched the young woman dance kahiko, the lights low, the movements of the ancient hula precise and strong, he knew that he had to make the shift from commercial to fine art, from L.A. back to Hawai‘i. Christine, carrying their fourth child, had wanted all their babies to be born in Hawai‘i, so there was no protest from her, despite the loss of economic security. Soon they were Hilo-bound, following a lead from another friend.

Hilo was a town in which neither had lived before. Philip began drawing and painting ‘ohi‘a lehua (the blossoms of the ‘ohi‘a tree) in the forests near Volcano, which drew him into the mo‘olelo (stories) of old Hawai‘i that revolve around Pele, and to Pele herself as he traipsed through her forests and studied her favorite flowers. But living in Hilo taxed the Sabados’ monetary reserves, and after 18 months they moved to Maui, where they found, Philip says, “a community that supports its artists.”

Hilo was a town in which neither had lived before. Philip began drawing and painting ‘ohi‘a lehua (the blossoms of the ‘ohi‘a tree) in the forests near Volcano, which drew him into the mo‘olelo (stories) of old Hawai‘i that revolve around Pele, and to Pele herself as he traipsed through her forests and studied her favorite flowers. But living in Hilo taxed the Sabados’ monetary reserves, and after 18 months they moved to Maui, where they found, Philip says, “a community that supports its artists.”

It wasn’t all that easy to be an artist on Maui 20 years ago, Philip confesses. When Christine took his paintings to the galleries in Lahaina, they were rejected as being “too Hawaiian.” Christine had to gather the courage to tell her husband that the gallery owners didn’t find the Hawaiian women in his paintings beautiful. “Tell them to go to Moloka‘i,” Philip replied, “and see how beautiful Hawaiian women are, inside out, outside in. They’re not the cover photos of the magazines. They’re real.” In the mid-’70s, while at the Honolulu Academy of Art, Philip had noticed that all the illustrations of Hawai‘i came from the Mainland. “How come they’re not using local artists to create Hawai‘i?” he had wondered. And here he was, a few years later, with the answer, a Moloka‘i boy painting the Hawai‘i he knew so well, told it wasn’t pretty enough. But he kept at it, with Christine encouraging him to also “paint flowers with mana” (spirit), which sold well, so that they could support themselves.

In 1987, the Maui Kupuna Council chose a Philip Sabado painting titled Ka La Kapu to represent the “Ho‘olako: Year of the Hawaiian” poster. The painting features the young kahiko dancer he saw that night in Las Vegas: a poster of a beautiful Hawaiian woman painted by a local artist! Philip has since been commissioned by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts to paint the interpretive signs for ‘Iao Valley State Park’s cultural sites, and to create a 40-foot mural depicting Moloka‘i’s mo‘olelo for Kaunakakai Elementary School. In 2004 and 2005 he was chosen by Maui County as Maui’s Artist of the Year.

Philip describes his style as traditional, explaining that he uses a glazing technique, layering one color on top of another. This develops an intensity of color that vibrates off the canvas, like the essence of the Hawaiian scenes he paints.

He also paints plenty of ti. My mother asks him about these paintings. “You like painting ti leaf,” she says. “I love planting ti,” he responds. It is this intimate connection with his subject matter that brings life to his work. This and the host of departed kupuna (elders) who hover around him. This is what Philip’s career has evolved into: a silent communication with spirit.

The huge canvas in the corner of the studio is an example: Philip starts with an image, like the canoe in the foreground. He doesn’t have a plan. He just begins, open to whatever will follow. Like clouds, something—or someone—starts to take shape. Philip keeps painting. Someone else may appear. Philip says, “Oh, so you like come too.” It grows from there. Eventually, Philip will invite living kupuna and kumu (teachers) to come look at the painting, to ensure that he has represented Hawai‘i correctly. It is then that he may learn the mo‘olelo on the canvas as the kupuna explain to him what he has painted, the significance of a ti plant or a color. Or who the figures are who have appeared, wanting to be part of the scene.

I ask Philip why he has been chosen by “them,” the kupuna living and deceased, to carry forth the stories in this way. “Because I have the skill,” Philip answers. He means this modestly, referring to the time he spent learning to perfect something he loves doing. Plus, he says, “I listen. I believe. I don’t question. It’s 150 percent trust.”

I recall what I felt when I first entered Philip’s studio, imagining I was alone and finding that I was in the presence of my grandfather and of Hawaiian kupuna who have passed—they were all hanging out in that large, clean, open space, like the students I saw on the next visit. Like the faces taking shape in the clouds.

Visit www.sabadostudios.com or call (808) 249-0980.