Rita Goldman

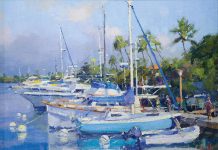

Seeing Andrea Razzauti’s vibrant landscapes for the first time is a little like opening the door of Dorothy’s tornado-tossed farmhouse and discovering yourself in Oz. The settings are exotic, with colors that transport them into the realm of imagination.

Seeing Andrea Razzauti’s vibrant landscapes for the first time is a little like opening the door of Dorothy’s tornado-tossed farmhouse and discovering yourself in Oz. The settings are exotic, with colors that transport them into the realm of imagination.

“My style is modern poetic realism,” Razzauti says in a rich Italian accent.

It’s a style the artist evolved during nearly four decades of painting and exhibiting throughout Europe, the U.S. and Asia. Razzauti moved here in 1998, living on Hawai‘i Island before settling on Maui, a place he says reminds him a lot of the Tuscan Riviera.

“When you move to Hawai‘i from a country like Italy, you start from zero,” he says. “You eliminate history, and dive into this organic tropical environment with its different light, different fish, different flowers. For an artist it is very stimulating.”

In the living room of Razzauti’s modest bungalow overlooking the South Maui coast, an easel props up a work in progress. Yet for the moment, the painting is incidental; what Razzauti is eager to share is not image, but sound. He opens the door to a bedroom-turned-studio, filled with speakers, a keyboard, guitars . . . accoutrements of Razzauti’s other passion.

“I say art is music, music is art. They complement each other. If an emotion makes me remember beautiful white sand and a blue horizon, I want to do a painting. But if I have my guitar, and the same picture in my mind, I compose a white-sand piece of music. It’s two forms of expression, with brush, with strings, but the same emotion.”

Razzauti grew up steeped in both forms of expression. His father was a professional painter whose hobby was the violin. His mother and grandmother played musical instruments; an aunt taught piano at the conservatory. By the time he was fourteen, Razzauti was a serious student of art, and a self-taught guitarist who idolized Jimi Hendrix.

After high school—where Razzauti cheerfully admits he excelled in art and nothing else—he enrolled in art school in Pisa. “The art school expected students not to know that much about the material. I went there after five years of watching my father,” he explains. “I would ask him questions with the curiosity of a young child: ‘Why do you use a palette that is glass instead of wood?’ ‘How do you clean the brush?’ ‘How do you approach the canvas?’ When my father had a show, he always brought me with him. I met many of his colleagues. It was fascinating to see different styles.”

Razzauti decided to quit school and study on his own. By the time he was seventeen, his work was in a gallery, and collectors were showing an interest.

“They knew I am the son of my father, and they saw that I was a good painter,” he says.

Razzauti didn’t emulate his father’s Expressionist style. “I respected him as an artist and educated man, but while I was paying attention, I was trying to do my own thing.”

Surprisingly, the elder Razzauti praised Andrea more for his music than for his art. “He thought music was the bigger gift,” Andrea explains. “My father was not at the same level as a violin player that he was as a painter. He would look at a musician and say, ‘Wow, I can’t do that.’”

When he was fourteen, Razzauti formed a band with some friends. “My father was driving me all the time to gigs in his aquamarine Alfa Romeo, then sneaking in see me. I was so embarrassed! Well, I was fourteen.

“He decided to buy a night club with the father of another member of my band. ‘Why are we driving these guys to play everywhere?’ he said. ‘Let’s buy our own place.’ We played there every Saturday and Sunday. During the week I was doing my art.”

The year Razzauti turned eighteen, his father died.

“I stopped playing with the band after my father died,” he says. By then, the music of the sixties that had inspired him was losing ground to disco. “We lost the poetic way to approach the music. Jimi Hendrix died.”

Razzauti started listening to different genres, composing his own pieces. But he no longer performed in public. Instead, he threw himself into his painting.

“The first years, I worked mostly en plein air to study the light and shadow at different times of the day, with different weather—rain, snow, sun. There was at the end of the 1800s a famous movement called Macchiaioli, the parallel of the French Impressionists, but more pure. The Impressionists did large paintings; Macchiaioli was small canvasses, what you can do in one hour before the light changes. It was a completely revolutionary way to approach art. Where I was born is the same town as where the Macchiaioli movement was born, so we get this big influence.

“I painted en plein air ten years in Italy and France. Then I completely broke with the technique. Why? If I didn’t have a beautiful location, I couldn’t paint. I didn’t want to become a slave of the subject.

“After ten years of painting that way, every day, month after month, I could do it in my memory. I understood that it doesn’t matter where you are; you can paint anything. So I decide to close myself in the studio to focus on developing the painting in my brain, and then putting it on canvas. I became [a little] more of a surrealist. My style is not abstract, even though it’s my interpretation. I never use a photograph. It’s the memory of a scene, an emotion filtered through memory. The memory is not completely realistic; it is blended with your soul.”

Though it’s been decades since Razzauti pursued music as a profession, it too is in his soul. Some years ago, the artist walked into an LA guitar shop and struck up a conversation with a fellow patron who turned out to be Paul Brown, the Grammy Award-winning producer. Brown was so taken with Razzauti’s painting White Sand that he used it as title and cover art for one of his CDs. Brown is also producing a forthcoming album of Razzauti’s music that features Grammy-winning vocalist Patty Austin. Razzauti hopes to launch his CD with a party at Lahaina Galleries, the place to go to see his fine art. “You will have the vision and the sound. The piece on canvas and the music complement each other.”

Whatever his genre, Razzauti lives by a straightforward credo: “Believe in what you’re doing. . . . If I’m satisfied when I sign the painting, I’m pretty confident I will satisfy somebody else.”