Rob Hawes, owner of Tradewind Graphics in Kihei, happens to be deeply immersed in tiki culture. He recently attended the annual Tiki Oasis convention. Held in San Diego, it occupied the entire Crown Plaza Hotel (formerly known as the Hanalei). “Everyone wears vintage aloha shirts, listens to exotica music [Martin Denny, no doubt], and drinks rum drinks.” Rob and his fellow aficionados are perpetuating the Polynesian Pop Culture that took root in the 1950s, beginning with home tiki bars in converted basements, then launching into Hawaiian-themed restaurants. Rob says that the disco era knocked out a lot of these places, but they’re making a comeback — for example, Smuggler’s Cove in San Francisco, and the Tacoma Cabana with its No Ka ‘Oi Mai Tai sporting rums from Jamaica, Guyana, and Trinidad. The draw for Rob is tiki mugs. He owns more than 500 and is creating more himself. He’ll be showing and selling them at the Made in Maui County Festival at the Maui Arts & Cultural Center in November. He admits that Polynesian Pop is a “dreamed-up fantasy version of Hawai‘i,” not true Hawaiiana. Tikis are not Hawaiian.

Rob Hawes, owner of Tradewind Graphics in Kihei, happens to be deeply immersed in tiki culture. He recently attended the annual Tiki Oasis convention. Held in San Diego, it occupied the entire Crown Plaza Hotel (formerly known as the Hanalei). “Everyone wears vintage aloha shirts, listens to exotica music [Martin Denny, no doubt], and drinks rum drinks.” Rob and his fellow aficionados are perpetuating the Polynesian Pop Culture that took root in the 1950s, beginning with home tiki bars in converted basements, then launching into Hawaiian-themed restaurants. Rob says that the disco era knocked out a lot of these places, but they’re making a comeback — for example, Smuggler’s Cove in San Francisco, and the Tacoma Cabana with its No Ka ‘Oi Mai Tai sporting rums from Jamaica, Guyana, and Trinidad. The draw for Rob is tiki mugs. He owns more than 500 and is creating more himself. He’ll be showing and selling them at the Made in Maui County Festival at the Maui Arts & Cultural Center in November. He admits that Polynesian Pop is a “dreamed-up fantasy version of Hawai‘i,” not true Hawaiiana. Tikis are not Hawaiian.

The popular imagination is not so discrete. For a long time now, civilized people have obsessed with “going native,” and Hawai‘i is always somewhere in their mythic landscapes.

The popular imagination is not so discrete. For a long time now, civilized people have obsessed with “going native,” and Hawai‘i is always somewhere in their mythic landscapes.

That dream has deep cultural roots. You can take it all the way back to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which a complicated group of characters gets shipwrecked on a magical island. Later came Robinson Crusoe (1719), the Swiss Family Robinson (1812), and Herman Melville’s Typee (1846), in which he wrote about being stranding among cannibals in the Marquesas.

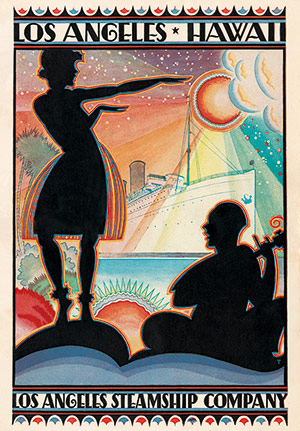

None of these works actually touch Hawai‘i. But consider the swooning literary fruitcake Charles Warren Stoddard, who published Summer Cruising in the South Seas (1874) after visiting these islands. (Hawai‘i is not in the “South Seas,” but never mind. Hawaiiana makes its own maps.)

Stoddard wrote: “The simple and natural life of the islands beguiles me; all the rites of savagedom find a responsive echo in my heart . . . like a dream dimly remembered, and at last realized; it must be that the untamed spirit of some aboriginal ancestor quickens my blood.” He reveled with “brown and brawny heathendom” in “dear drowsy little Lahaina.”

And on it goes. At the start of the 1900s, in Idaho, a pencil-sharpener salesman named Ed Burroughs was reading a lot of pulp-fiction magazines while wondering what to do with his life. He thought that he could write pulp fiction as well as the next guy. In fact, he wanted to “find out how bad a book he could write and get away with it.”

So he imagined a feral white man raised by apes. In an early black-and-white talkie, our man Tarzan manages to convince a white woman, Jane, to go feral, too. Jane writhes in the morning light of the wild man’s treetop nest and giggles. “Oh, Tarzan, what am I doing here—with you, not a bit afraid?” In face, hairstyle, and languid posture, the actress is an exact copy of the hula-hula girl depicted in the old Art Deco enticements to the Hawaiian Islands.